Mapping Images to Scene Graphs with Permutation-Invariant Structured Prediction

The paper Mapping Images to Scene Graphs with Permutation-Invariant Structured Prediction was written by Roei Herzig* from Tel Aviv University, Moshiko Raboh* from Tel Aviv University, Gal Chechik from Google Brain, Bar-Ilan University, Jonathan Berant from Tel Aviv University, and Amir Globerson from Tel Aviv University. This paper is part of the NIPS 2018 conference to be hosted in December 2018 at Montréal, Canada. This paper summary is based on version 3 of the pre-print (as of May 2018) obtained from arXiv

(*) Equal contribution

Motivation

In the field of artificial intelligence, a major goal is to enable machines to understand complex images, such as the underlying relationships between objects that exist in each scene, and the global context to interpret this scene. A natural modelling framework for capturing such effects is structured prediction, which seeks to predict structured objects (such as graphs with nodes and edges) rather than scalar classes. Although these models capture both complex labels and interactions between labels, there is a disconnect for what guidelines should be used when leveraging deep learning. This paper introduces a design principle for such models that stem from the concept of permutation invariance and proves state of the art performance on models that follow this principle.

The primary contributions that this paper makes include:

- Deriving sufficient and necessary conditions for respecting graph-permutation invariance in deep structured prediction architectures.

- Empirically proving the benefit of graph-permutation invariance.

- Developing a state-of-the-art model for scene graph predictions over a large set of complex visual scenes.

Introduction

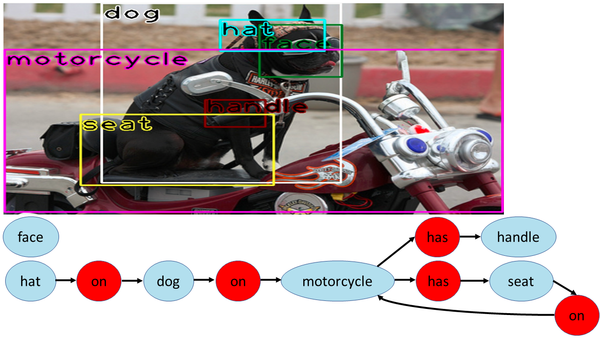

In order to make a machine to interpret complex visual scenes, it must recognize and understand both objects and relationships between the objects in the scene. A scene graph is a representation of the set of objects and relations that exist in the scene, where objects are represented as nodes, relations are represented as edges connecting the different nodes. Hence, the prediction of the scene graph is analogous to inferring the joint set of objects and relations of a visual scene.

Given that objects in scenes are interdependent on each other, joint prediction of the objects and relations is necessary. The field of structured prediction, which involves the general problem of inferring multiple inter-dependent labels, is of interest for this problem. Structured prediction has attracted considerable attention because it applies to many learning problems and poses unique theoretical and applied challenges (e.g., see Belanger et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2015; Taskar et al., 2004).

In structured prediction models, a score function [math]\displaystyle{ s(x, y) }[/math] is defined to evaluate the compatibility between label [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] and input [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. For instance, when interpreting the scene of an image, [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] refers to the image itself, and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] refers to a complex label, which contains both the objects and the relations between objects. As with most other inference methods, the goal is to find the label [math]\displaystyle{ y^* }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ s(x,y) }[/math] is maximized, [math]\displaystyle{ y^*=argmax_y \: s(x,y) }[/math]. However, the major concern is that the space for possible label assignments grows exponentially with respect to input size. For example, although an image may seem very simple, the corpus containing possible labels for objects may be very large, rendering it difficult to optimize the scoring function.

The paper presents an alternative approach, for which input [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] is mapped to structured output [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] using a "black box" neural network, omitting the definition of a score function. The main concern for this approach is the determination of the network architecture.

The model is evaluated by firstly demonstrating the importance of permutation invariance on a synthetic data set. The approach laid out by the authors is then shown to respect permutation invariance, and results are compared to a competitive benchmark. This method achieves state-of-the-art results.

Structured prediction

This paper further considers structured predictions using score-based methods. For structured predictions that follow a score-based approach, a score function [math]\displaystyle{ s(x, y) }[/math] is used to measure how compatible label [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] is for input [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and is also used to infer a label by maximizing [math]\displaystyle{ s(x, y) }[/math]. To optimize the score function, previous works have decomposed [math]\displaystyle{ s(x,y) = \sum_i f_i(x,y) }[/math], into a set of simpler functions [math]\displaystyle{ f_i(x,y) }[/math], in order to facilitate efficient optimization which is done by optimizing the local score function, [math]\displaystyle{ \max_y f_i(x,y) }[/math], with a small subset of the [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] variables.

Recently, modeling the [math]\displaystyle{ f_i }[/math] functions as deep networks is a new interest. In such area of structured predictions, the most commonly-used score functions include the singleton score function [math]\displaystyle{ f_i(y_i, x) }[/math] and pairwise score function [math]\displaystyle{ f_{ij} (y_i, y_j, x) }[/math]. Previous works explored a two-stage architectures (learn local scores independently of the structured prediction goal), end-to-end architectures (to include the inference algorithm within the computation graph), and modelling global factors.

Advantages of using score-based methods

- Allow for intuitive specification of local dependencies between labels, and how they map to global dependencies

- Linear score functions offer natural convex surrogates

- Inference in large label space is sometimes possible via exact algorithms or empirically accurate approximations

The concern for modeling score functions using deep networks is that learning may no longer be convex. Hence, the paper presents properties for how deep networks can be used for structured predictions by considering architectures that do not require explicit maximization of a score function.

Background, Notations, and Definitions

We denote [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] as a structured label where [math]\displaystyle{ y = [y_1, \dots, y_n] }[/math]

Score functions: for score-based methods, the score is defined as either the sum of a set of singleton scores [math]\displaystyle{ f_i = f_i(y_i, x) }[/math] or the sum of pairwise scores [math]\displaystyle{ f_{ij} = f_{ij}(y_i, y_j, x) }[/math].

Let [math]\displaystyle{ s(x,y) }[/math] be the score of a score-based method. Then:

[math]\displaystyle{ s(x,y) = \begin{cases} \sum_i f_i ~ \text{if we have a set of singleton scores}\\ \sum_{ij} f_{ij} ~ \text{if we have a set of pairwise scores } \\ \end{cases} }[/math]

Inference algorithm: an inference algorithm takes input set of local scores (either [math]\displaystyle{ f_i }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ f_{ij} }[/math]) and outputs an assignment of labels [math]\displaystyle{ y_1, \dots, y_n }[/math] that maximizes score function [math]\displaystyle{ s(x,y) }[/math]

Graph labeling function: a graph labeling function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} : (V,E) \rightarrow Y }[/math] is a function that takes input of an ordered set of node features [math]\displaystyle{ V = [z_1, \dots, z_n] }[/math] and an ordered set of edge features [math]\displaystyle{ E = [z_{1,2},\dots,z_{i,j},\dots,z_{n,n-1}] }[/math] to output set of node labels [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{y} = [y_1, \dots, y_n] }[/math]. For instance, [math]\displaystyle{ z_i }[/math] can be set equal to [math]\displaystyle{ f_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ z_{ij} }[/math] can be set equal to [math]\displaystyle{ f_{ij} }[/math].

For convenience, the joint set of nodes and edges will be denoted as [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{z} }[/math] to be a size [math]\displaystyle{ n^2 }[/math] vector ([math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] nodes and [math]\displaystyle{ n(n-1) }[/math] edges).

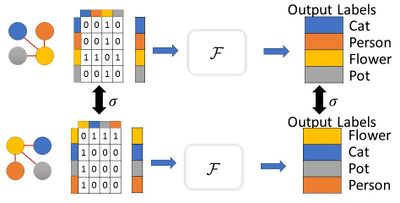

Permutation: Let [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] be a set of node and edge features. Given a permutation [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ \{1,\dots,n\} }[/math], let [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(z) }[/math] be a new set of node and edge features given by [[math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(z)]_i = z_{\sigma(i)} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ [\sigma(z)]_{i,j} = z_{\sigma(i), \sigma(j)} }[/math]

One-hot representation: [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{1}[j] }[/math] be a one-hot vector with 1 in the [math]\displaystyle{ j^{th} }[/math] coordinate

Permutation-Invariant Structured prediction

With permutation-invariant structured prediction, we would expect the algorithm to produce the same result given the same score function. For instance, consider the case where we have label space for 3 variables [math]\displaystyle{ y_1, y_2, y_3 }[/math] with input [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{z} = (f_1, f_2, f_3, f_{12}, f_{13}, f_{23}) }[/math] that outputs label [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{y} = (y_1^*, y_2^*, y_3^*) }[/math]. Then if the algorithm is run on a permuted version input [math]\displaystyle{ z' = (f_2, f_1, f_3, f_{21}, f_{23}, f_{13}) }[/math], we would expect [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{y} = (y_2^*, y_1^*, y_3^*) }[/math] given the same score function.

Graph permutation invariance (GPI): a graph labeling function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math] is graph-permutation invariant, if for all permutations [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ \{1, \dots, n\} }[/math] and for all nodes [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F}(\sigma(\mathbf{z})) = \sigma(\mathcal{F}(\mathbf{z})) }[/math]. Practically speaking, graph permutation means that the same graph is constructed, no matter the order in which elements are predicted. In scene graph generation approaches, Region Proposal Networks are often used as an initial pre-processing step. The results from these (cropped images representing bounding boxes) are then sequentially fed through a respective vertex (or edge) detection network. The idea behind Permutation Invariance is that no matter the order these are passed in, the final scene graph is identical. In effect, this means not connecting vertices that should not be connected simply because a more promising vertex has not yet been identified.

The paper presents a theorem on the necessary and sufficient conditions for a function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math] to be graph permutation invariant. Intuitively, because [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math] is a function that takes an ordered set [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] as input, the output on [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{z} }[/math] could very well be different from [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(\mathbf{z}) }[/math], which means [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math] needs to have some sort of symmetry in order to sustain [math]\displaystyle{ [\mathcal{F}(\sigma(\mathbf{z}))]]_k = [\mathcal{F}(\mathbf{z})]_{\sigma(k)} }[/math].

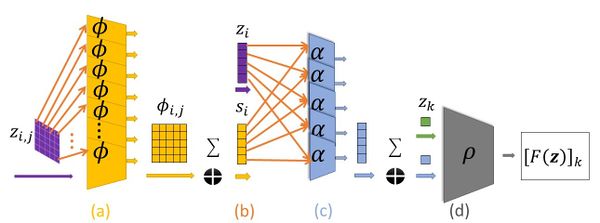

Theorem 1

Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math] be a graph labeling function. Then [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math] is graph-permutation invariant if and only if there exist functions [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha, \rho, \phi }[/math] such that for all [math]\displaystyle{ k=1, .., n }[/math]: \begin{align} [\mathcal{F}(\mathbf{z})]_k = \rho(\mathbf{z}_k, \sum_{i=1}^n \alpha(\mathbf{z}_i, \sum_{i\neq j} \phi(\mathbf{z}_i, \mathbf{z}_{i,j}, \mathbf{z}_j))) \end{align} where [math]\displaystyle{ \phi: \mathbb{R}^{2d+e} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^L, \alpha: \mathbb{R}^{d + L} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{W}, p: \mathbb{R}^{W+d} \rightarrow \mathbb{R} }[/math].

Notice that for the dimensions of inputs and outputs, [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] refers to the number of singleton features in [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] refers to the number of edges.

Proof Sketch for Theorem 1

The proof of this theorem can be found in the paper. A proof sketch is provided below:

For the forward direction (function that follows the form set out in equation (1) is GPI):

- Using definition of permutation [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math], and rewriting [math]\displaystyle{ [F(z)]_{\sigma(k)} }[/math] in the form from equation (1)

- Second argument of [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] is invariant under [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math], since it takes the sum of all indices [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and all other indices [math]\displaystyle{ j \neq i }[/math].

For the backward direction (any black-box GPI function can be expressed in the form of equation 1):

- Construct [math]\displaystyle{ \phi, \alpha }[/math] such that second argument of [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] contains all information about graph features of [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math], including edges that the features originate from

- Assume each [math]\displaystyle{ z_k }[/math] uniquely identifies the node and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math] is a function only of pairwise features [math]\displaystyle{ z_{i,j} }[/math]

- Construct [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] be a perfect hash function with [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] buckets, and [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] which maps pairwise features to a vector of size [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ * }[/math]Construct [math]\displaystyle{ \phi(z_i, z_{i,j}, z_j) = \mathbf{1}[H(z_j)] z_{i,j} }[/math], which intuitively means that [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] stores [math]\displaystyle{ z_{i,j} }[/math] in the unique bucket for node [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]

- Construct function [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] to output a matrix [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^{L \times L} }[/math] that maps each pairwise feature into unique positions ([math]\displaystyle{ \alpha(z_i, s_i) = \mathbf{1}[H(z_i)]s_i^T }[/math])

- Construct matrix [math]\displaystyle{ M = \sum_i \alpha(z_i,s_i) }[/math] by discarding rows/columns in [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] that do not correspond to original nodes (which reduces dimension to [math]\displaystyle{ n\times n }[/math]; set [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math] to have same outcome as [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math], and set the output of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math] on [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] to be the labels [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{y} = y_1, \dots, y_n }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ * }[/math]The paper presents the proof for the edge features [math]\displaystyle{ z_{ij} }[/math] being scalar ([math]\displaystyle{ e = 1 }[/math]) for simplicity, which can be extended easily to vectors with additional indexing.

Although the results discussed previously apply to complete graphs (edges apply to all feature pairs), it can be easily extended to incomplete graphs. For incomplete graphs, the input to F only contains the features corresponding to valid edges of the graph. The authors are only interested in invariances that preserve the graph structure. Thus, in place of permutation-invariance, it is now an automorphism-invariance.

Implications and Applications of Theorem 1

Key Implications of Theorem 1

- Architecture "collects" information from the different edges of the graph, and does so in an invariant fashion using [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math]

- Architecture is parallelizable, since all [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] functions can be applied simultaneously. In contrast, recurrent models (Zellers et al. 2017) are harder to parallelize and are thus practically slower.

Some applications of Theorem 1

- Attention: the concept of attention can be implemented in the GPI characterization, with slight alterations to the functions [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math]. In attention each node aggregates features of neighbors through a function of neighbor's relevance. Which means the label of an entity could depend strongly on its close entity. The complete details can be found in the supplementary materials of the paper.

- RNN: recurrent architectures can maintain GPI property, since all GPI function [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math] are closed under composition. The output of one step after running [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{F} }[/math] will act as input for the next step, but maintain the GPI property throughout.

Related Work

- Architectural invariance: suggested recently in a 2017 paper called Deep Sets by Zaheer et al., which considers the case of invariance that is more restrictive.

- Deep structured prediction: previous work applied deep learning to structured prediction, for instance, semantic segmentation. Some algorithms include message passing algorithms, gradient descent for maximizing score functions, greedy decoding (inference of labels based on time of previous labels). For example, Xu et al. 2017 propose a novel end-to-end model that generates structured scene representation, and their model solves the scene graph inference problem using standard RNNs and learns to iteratively improves its predictions via message passing. Apart from those algorithms, deep learning has been applied to other graph-based problems such as the Travelling Salesman Problem (Bello et al., 2016; Gilmer et al., 2017; Khalil et al., 2017). However, none of the previous work specifically address the notion of invariance in the general architecture, but rather focus on message passing architectures that can be generalized by this paper.

- Scene graph prediction: scene graph extraction allows for reasoning, question answering, and image retrieval (Johnson et al., 2015; Lu et al., 2016; Raposo et al., 2017). Some other works in this area include object detection, action recognition, and even the detection of human-object interactions (Liao et al., 2016; Plummer et al., 2017). Additional work has been done with the use of message passing algorithms (Xu et al., 2017), word embeddings (Lu et al., 2016), and end-to-end prediction directly from pixels (Newell & Deng, 2017). A notable mention is NeuralMotif (Zellers et al., 2017), which the authors describe as the current state-of-the-art model for scene graph predictions on Visual Genome dataset. It uses an RNN that supplies global context by reading the independent predictions sequentially for each entity and relation and then conducts further refinement on the predictions. The NeuralMotif model has a fixed order in which the RNN reads its inputs and thereby maintains GPI. However, this fixed order is not guaranteed to be optimal.

- Burst Image Deblurring Using Permutation Invariant Convolutional Neural Networks: similar ideas were applied, where Permutation Invariant CNN, are used to restore sharp and noise-free images from bursts of photographs affected by hand tremor and noise. This presented good quality images with lots of details for challenging datasets.

Experimental Results

The authors evaluated the advantage of GPI architectures empirically. They first utilized synthetic graph labeling and then used scene-graph classification for mapping images.

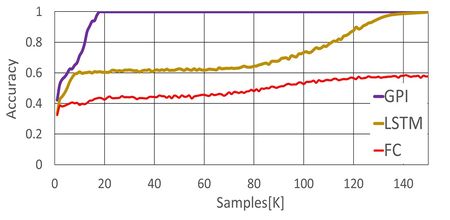

Synthetic Graph Labeling

The authors created a synthetic problem to study GPI. This involved using an input graph [math]\displaystyle{ G = (V,E) }[/math] where each node [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] belongs to the set [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma(i) \in \{1, \dots, K\} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] is the number of samples. The task is to compute for each node, the number of neighbours that belong to the same set (i.e. finding the label of the node [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ y_i = \sum_{j \in N(i)} \mathbf{1}[\Gamma(i) = \Gamma(j)] }[/math]) . Then, random graphs (each with 10 nodes) were generated by sampling edges, and the set [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma(i) \in \{1, \dots, K\} }[/math]for each node independently and uniformly. The node features of the graph [math]\displaystyle{ z_i \in \{0,1\}^K }[/math] are one-hot vectors of [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma(i) }[/math], and each pairwise edge feature [math]\displaystyle{ z_{ij} \in \{0, 1\} }[/math] denote whether the edge [math]\displaystyle{ ij }[/math] is in the edge set [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math]. 3 architectures were studied in this paper:

- GPI-architecture for graph prediction (without attention and RNN)

- LSTM: replacing [math]\displaystyle{ \sum \phi(\cdot) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \sum \alpha(\cdot) }[/math] in the form of Theorem 1 using two LSTMs with state size 200, reading their input in random order

- Fully connected feed-forward network: with 2 hidden layers, each layer containing 1,000 nodes; the input is a concatenation of all nodes and pairwise features, and the output is all node predictions

The results show that the GPI architecture requires far fewer samples to converge to the correct solution.

This experimental result is meant to demonstrate sample complexity. For fairness, all three models were constructed with a similar number of trainable parameters. The results tie back in with the author's comment that a black-box model which violates permutation invariant structure wastes capacity on learning it at training time. This illustrates the advantage of an architecture with a proper inductive bias.

Scene-Graph Classification

Applying the concept of GPI to Scene-Graph Prediction (SGP) is the main task of this paper. The input to this problem is an image, along with a set of annotated bounding boxes for the entities in the image. The goal is to correctly label each entity within the bounding boxes and the relationship between every pair of entities, resulting in a coherent scene graph.

The authors describe two different types of variables to predict. The first type is entity variables [math]\displaystyle{ [y_1, \dots, y_n] }[/math] for all bounding boxes, where each [math]\displaystyle{ y_i }[/math] can take one of L values and refers to objects such as "dog" or "man". The second type is relation variables [math]\displaystyle{ [y_{n+1}, \cdots, y_{n^2}] }[/math], where each [math]\displaystyle{ y_i }[/math] represents the relation (e.g. "on", "below") between a pair of bounding boxes (entities).

The scene graph and contain two types of edges:

- Entity-entity edge: connecting two entities [math]\displaystyle{ y_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y_j }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \leq i \neq j \leq n }[/math]

- Entity-relation edges: connecting every relation variable [math]\displaystyle{ y_k }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ k \gt n }[/math] to two entities

The feature set [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{z} }[/math] is based on the baseline model from Zellers et al. (2017). For entity variables [math]\displaystyle{ y_i }[/math], the vector [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{z}_i \in \mathbb{R}^L }[/math] models the probability of the entity appearing in [math]\displaystyle{ y_i }[/math]. [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{z}_i }[/math] is augmented by the coordinates of the bounding box. Similarly for relation variables [math]\displaystyle{ y_j }[/math], the vector [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{z}_j \in \mathbb{R}^R }[/math], models the probability of the relations between the two entities in [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]. For entity-entity pairwise features [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{z}_{i,j} }[/math], there is a similar representation of the probabilities for the pair. The SGP outputs probability distributions over all entities and relations, which will then be used as input recurrently to maintain GPI. Finally, word embeddings are used and concatenated for the most probable entity-relation labels.

Components of the GPI architecture (ent for entity, rel for relation)

- [math]\displaystyle{ \phi_{ent} }[/math]: network that integrates two entity variables [math]\displaystyle{ y_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y_j }[/math], with input [math]\displaystyle{ z_i, z_j, z_{i,j} }[/math] and output vector of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^{n_1} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_{ent} }[/math]: network with inputs from [math]\displaystyle{ \phi_{ent} }[/math] for all neighbours of an entity, and uses attention mechanism to output vector [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^{n_2} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_{ent} }[/math]: network with inputs from the various [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R}^{n_2} }[/math] vectors, and outputs [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] logits to predict entity value

- [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_{rel} }[/math]: network with inputs [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_{ent} }[/math] of two entities and [math]\displaystyle{ z_{i,j} }[/math], and output into [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] logits

Set-up and Results

Dataset: based on Visual Genome (VG) by (Krishna et al., 2017), which contains a total of 108,077 images annotated with bounding boxes, entities, and relations. An average of 12 entities and 7 relations exist per image. For a fair comparison with previous works, data from (Xu et al., 2017) for train and test splits were used. The authors used the same 150 entities and 50 relations as in (Xu et al., 2017; Newell & Deng, 2017; Zellers et al., 2017). Hyperparameters were tuned using a 70K/5K/32K split for training, validation, and testing respectively.

Training: all networks were trained using the Adam optimizer, with a batch size of 20. The loss function was the sum of cross-entropy losses over all of entities and relations. Penalties for misclassified entities were 4 times stronger than that of relations. Penalties for misclassified negative relations were 10 times weaker than that of positive relations.

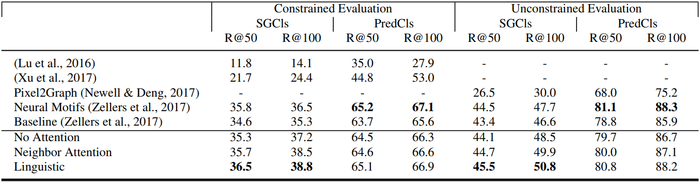

Evaluation: there are three major tasks when inferring from the scene graph. The authors focus on the following:

- SGCIs: given ground-truth entity bounding boxes, predict all entity and relations categories

- PredCIs: given annotated bounding boxes with entity labels, predict all relations

The evaluation metric Recall@K (shortened to R@K) is drawn from (Lu et al., 2016). This metric is the fraction of correct ground-truth triplets that appear within the [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] most confident triplets predicted by the model. Graph-constrained protocol requires the top-[math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] triplets to assign one consistent class per entity and relation. The unconstrained protocol does not enforce such constraint.

Models and baselines: The authors compared variants of the GPI approach against four baselines, state-of-the-art models on completing scene graph sub-tasks. To maintain consistency, all models used the same training/testing data split, in addition to the preprocessing as per (Xu et al., 2017).

Baselines from existing state-of-the-art models

- (Lu et al., 2016): use of word embeddings to fine-tune the likelihood of predicted relations

- (Xu et al., 2017): message passing algorithm between entities and relations to iteratively improve feature map for prediction

- (Newell & Deng, 2017): Pixel2Graph, uses associative embeddings to produce a full graph from image

- (Zellers et al., 2017): NeuralMotif method, encodes global context to capture higher-order motif in scene graphs; Baseline outputs entities and relations distributions without using global context

GPI models

- GPI with no attention mechanism: simply following Theorem 1's functional form, with summation over features

- GPI NeighborAttention: same GPI model, but considers attention over neighbours features

- GPI Linguistic: similar to NeighborAttention model, but concatenates word embedding vectors

Key Results: The GPI Linguistic approach outperforms all baseline for SGCIs, and has similar performance to the state of the art NeuralMotifs method. The authors argue that PredCI is an easier task with less structure, yielding high performance for the existing state of the art models.

Conclusion

A deep learning approach was presented in this paper to structured prediction, which constrains the architecture to be invariant to structurally identical inputs. This approach relies on pairwise features which are capable of describing inter-label correlations and inherits the intuitive aspect of score-based approaches. The output produced is invariant to equivalent representation of the pairwise terms.

As future work, the axiomatic approach can be extended; for example in image labeling, geometric variances such as shifts or rotations may be desired (or in other cases invariance to feature permutations may be desired). Additionally, exploring algorithms that discover symmetries for deep structured prediction when the invariant structure is unknown and should be discovered from data is also an interesting extension of this work.

Critique

The paper's contribution comes from the novelty of the permutation invariance as a design guideline for structured prediction. Although not explicitly considered in many of the previous works, the idea of invariance in architecture has already been considered in Deep Sets by (Zaheer et al., 2017). This paper characterizes relaxes the condition on the invariance as compared to that of previous works. In the evaluation of the benefit of GPI models, the paper used a synthetic problem to illustrate the fact that far fewer samples are required for the GPI model to converge to 100% accuracy. However, when comparing the true task of scene graph prediction against the state-of-the-art baselines, the GPI variants had only marginal higher Recall@K scores. The true benefit of this paper's discovery is the avoidance of maximizing a score function (leading computationally difficult problem), and instead directly producing output invariant to how we represent the pairwise terms.

References

Lu, Cewu, Krishna, Ranjay, Bernstein, Michael S., and Li, Fei-Fei. Visual relationship detection with language priors. In European Conf. Comput. Vision, pp. 852–869, 2016.

Roei Herzig, Moshiko Raboh, Gal Chechik, Jonathan Berant, Amir Globerson, Mapping Images to Scene Graphs with Permutation-Invariant Structured Prediction, 2018.

Belanger, David, Yang, Bishan, and McCallum, Andrew. End-to-end learning for structured prediction energy networks. In Precup, Doina and Teh, Yee Whye (eds.), Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, volume 70, pp. 429–439. PMLR, 2017.

Chen, Liang Chieh, Schwing, Alexander G, Yuille, Alan L, and Urtasun, Raquel. Learning deep structured models. In Proc. ICML, 2015.

Taskar, B., Guestrin, C., and Koller, D. Max margin Markov networks. In Thrun, S., Saul, L., and Schölkopf, B. (eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 16, pp. 25–32. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2004.

Zheng, Shuai, Jayasumana, Sadeep, Romera-Paredes, Bernardino, Vineet, Vibhav, Su, Zhizhong, Du, Dalong, Huang, Chang, and Torr, Philip HS. Conditional random fields as recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 1529–1537, 2015.

Additional resources from Moshiko Raboh's GitHub