CatBoost: unbiased boosting with categorical features

Presented by

Jessie Man Wai Chin, Yi Lin Ooi, Yaqi Shi, Shwen Lyng Ngew

Introduction

This paper presents a new boosting strategy: CatBoost with the key techniques of the algorithm. It is a new gradient boosting method and it outperforms other publicly available boosting methods in practice. The implementation of ordered boosting and the innovative way for processing categorical features are the two algorithmic advance introduced in CatBoost. It can deal with the prediction shift problem which is being discussed in details. In this paper, the authors provide the theoretical derivation of the algorithm along with the intuitive examples to demonstrate the strength and the efficiency of the model.

Previous Work

The CatBoost algorithm is new algorithm based on the gradient boosting method, which is a powerful machine-learning techniques with solid theoretical basis and strong predicting power. This new algorithm is built for the purpose of dealing with the prediction shift problem, which was discussed before in the paper [3,13] on boosting without a formal definition. This paper proposed this new algorithm and presented the analysis on how the existing problem is solved by this new algorithm. The previous work in paper [1,15,18,22] inspired the authors to propose a new algorithm to deal with categorical features. Here are the two main aspects considered in this new algorithm:

1. Ordered boosting, a modification of standard gradient boosting algorithm

2. Categorical features, a new algorithm for processing categorical features

Motivation

Gradient boosting is known to be a popular and powerful machine learning method that could potentially increase the accuracy of a model. It aims to identify strong predictors in a model by performing gradient descent. Nevertheless, there exists a statistical issue which makes gradient boosting less powerful as we intended it to be. The paper identified this issue as prediction shift caused by target leakage.

A prediction shift happens when there is a shift between the predicted model trained on the training samples and the distribution of the test samples. This often occurs as the predicted model is trained using all training samples and not all training samples are fully representative of the test samples. When the predicted model is trained using all training samples, it could lead to a biased model since the model has seen the labels during its learning stage. In gradient boosting, the current estimate [math]\displaystyle{ F^t }[/math] is based on the previous model [math]\displaystyle{ F^{t-1} }[/math] we built on earlier in each iteration. To better demonstrate a prediction shift, it essentially means that [math]\displaystyle{ F^{t-1}(\bf{x_k})|\bf{x_k} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \bf{x_k} }[/math] comes from training samples is shifted from [math]\displaystyle{ F^{t-1}(\bf{x})|\bf{x} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \bf{x} }[/math] comes from testing samples. This is caused by target leakage where the distribution of the estimated model is different from the distribution of the testing samples. Therefore, the model is biased and could lead to overfitting in some cases. To identify this issue, we will introduce ordered boosting which is the motivation behind categorical boosting.

Ordered Target Statistics

Before the introduction of ordered boosting, we will first introduce the concept of ordered target statistics. The reason why ordered target statistics is used in this algorithm is to avoid overfitting. In ordered target statistics, a random permutation on the training samples is constructed so that we train our model based on the new training samples in which our current model has never seen previously. Define a target statistic as [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{x}_k^i = E(y | x^i = x_k^i) }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] refers to [math]\displaystyle{ k^{th} }[/math] training samples and [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] refers to [math]\displaystyle{ i^{th} }[/math] categorical feature.

In ordered target statistics, a random permutation [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] is generated to help the algorithm to obtain training samples sequentially. For instance, if we would like to obtain [math]\displaystyle{ k^{th} }[/math] training samples, then [math]\displaystyle{ D_k = {x_j : \sigma(j)\lt \sigma(k)} }[/math]. Through this method, we can ensure that the model is unbiased as the trained model is obtained based on the new samples in which the model has never seen. In the traditional boosting method, the model is obtained based on all the training samples which could possibly lead to overfitting as we train the model based on what the model has seen previously. Therefore, the issue of overfitting motivates the idea of ordered target statistics which we will use to generate the permutations of our training samples.

Ordered Boosting

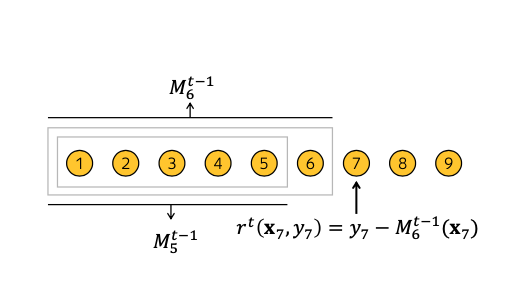

To overcome the prediction shift discussed in the previous section, ordered boosting is introduced. In ordered boosting, a new training dataset is obtained in each step of boosting. This means that the model is trained such that the model we obtained previously is applied to this set of new training samples. This guarantees that the model in which we have obtained previously has not seen the labels in the new training set. Therefore, the trained model at each step of boosting is not biased. To better illustrate this, assuming [math]\displaystyle{ M_t }[/math] is our current model in [math]\displaystyle{ {t+1}^{th} }[/math] iteration which is learned using only the first t samples, the residual [math]\displaystyle{ r^{t+1} = y_i - M_{t} }[/math] is unshifted since the model is trained without the observations in the new training set. This is supported by the generation of random permutations [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] of our training samples. To illustrate this idea, please see Figure (1).

In ordered boosting, the algorithm starts with generating [math]\displaystyle{ s+1 }[/math] independent random permutations [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_0, \sigma_1, \dots, \sigma_s }[/math] of the training dataset. [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_1, \dots, \sigma_s }[/math] contributes to the internal nodes of a tree where the evaluation of the splits takes place. [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_0 }[/math] contributes to the terminal nodes where the leaf value is determined. the algorithm starts with building a decision tree based on the base predictors. The same splitting criterion is used in building a decision tree in the context of ordered boosting. Note that the trees built under this model are symmetric as this helps to improvise the algorithm in terms of its runtime.

Define [math]\displaystyle{ M_{r,j}(i) }[/math] as our current model for the i-th sample based on the first j samples. A random permutation [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_r }[/math] is sampled from the [math]\displaystyle{ s+1 }[/math] independent random permutations of the training dataset. The random permutation, says [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_r }[/math], will then contribute to our construction of tree, [math]\displaystyle{ T_t }[/math].

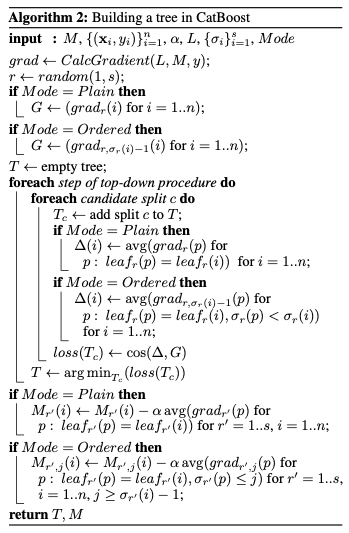

A gradient is computed at each step such that [math]\displaystyle{ grad_{r,j}(i)=\frac{\delta{L(y_i,M_{r,j}(i))}}{\delta{s}} }[/math]. The leaf value for the tree constructed based on the i-th sample will then be equals to the average of the gradients computed, which can be written as: $$\text{avg } grad_{r, \sigma_r(i)-1}$$ When a tree, [math]\displaystyle{ T_t }[/math] is constructed, the tree itself is used to boost all the existing models [math]\displaystyle{ M_{r',j} }[/math]. Finally, in our final model, [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math], the leaf values are computed using the standard gradient boosting procedure. Recall that [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma_0 }[/math] is used to determine the final leaf values. Therefore, once we obtain our final model, we match the training samples, says [math]\displaystyle{ i^{th} }[/math] sample, to [math]\displaystyle{ leaf_0(i) }[/math] and so on. See Figure 2 for the detailed algorithm of how CatBoost build a decision tree.

CatBoost Results

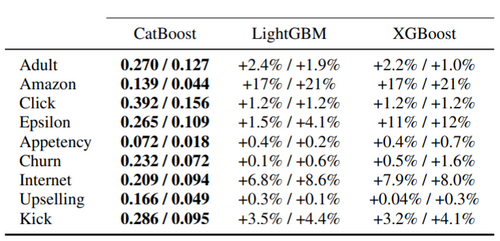

CatBoost is implemented as an algorithm for gradient boosting on decision trees. The algorithm is compared with the most popular open-source libraries – XGBoost and LightBGM. Categorical features are preprocessed using Ordered TS method for CatBoost. The results measured by logloss and zero-one loss are presented in Table 1. The statistical significance of performance is also presented in Table 1.

Besides, the running time for CatBoost Plain and LightGBM are the fastest ones followed by Ordered mode, which is about 1.7 times slower.

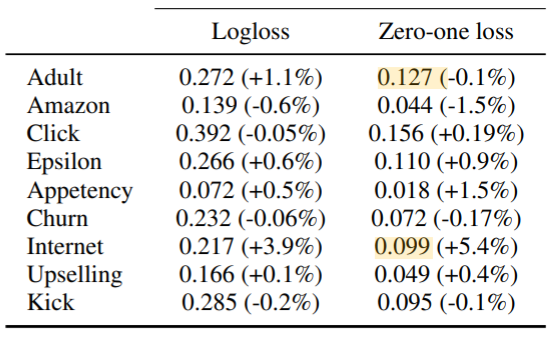

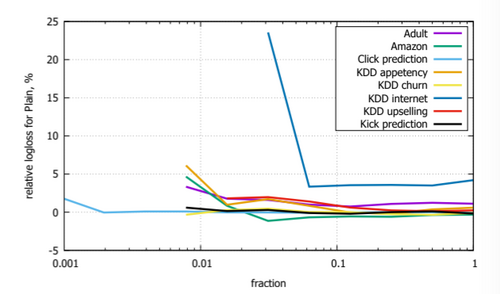

Comparison between boosting modes of CatBoost: Plain and Ordered is performed on all considered datasets, and the results are presented in Table 2. It is evident that Ordered mode is especially effective on smaller datasets, which supports the hypothesis that a larger bias has a negative effect on performance.

As illustrated in Figure 2, CatBoost is trained in Ordered and Plain modes on randomly filtered datasets to compare the generated losses. The relative performance of Plain modes becomes worse as the dataset size decreases.

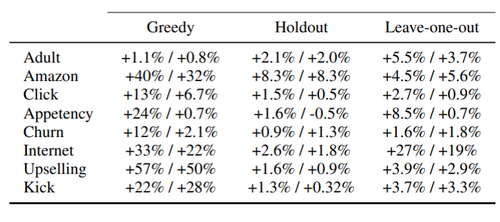

Different TSs options of CatBoost in Ordered boosting mode are being compared and the outcomes can be found in Table 3. Ordered TS used in CatBoost outscored all other approaches significantly. Among the baselines, the holdout TS is the best for a majority of the datasets.

Conclusion

CatBoost has two unique advancements: the implementation of ordered boosting and ordered TS to tackle the problem of prediction shift caused by target leakage present in all existing implementations of gradient boosting. The empirical result shows that CatBoost overperforms other GBDT packages on most of the datasets and thus CatBoost is an effective tool for use in supervised machine learning technique.

Critiques

Strength

1) The proposed algorithm and current statistical issues are presented in a simple manner

2) Solid empirical study of the new algorithm compared to current methodologies such as XGBoost and lightGBM

Weakness

1) This paper performs the experiment on heterogenous, categorical datasets. It does not show the performance of CatBoost relative to XGBoost and LightBoost when working with homogenous data. Hence, it may be biased to state that CatBoost outperforms other leading GBDT packages.

2) The tasks in the experiment are classification tasks. Author should include regression task to determine if the result holds for regression problem.

3) The hyper-parameter setting such as iteration, maximum tree depth and so on can impact CatBoost's performance relative to other GBDT implementation. CatBoost's Oblivious Decision Tree (ODT) are balanced by definition. The "maximum tree depth" will have an impact on the amount of memory and running time. Iteration specifies the maximum number of decision tree CatBoost will construct. It is possible that the author tune their hyperpararameter so that it looks better than for the baselines.

References

[1] L. Bottou and Y. L. Cun. Large scale online learning. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 217–224, 2004.

[2] L. Breiman. Out-of-bag estimation, 1996.

[3] L. Breiman. Using iterated bagging to debias regressions. Machine Learning, 45(3):261–277, 2001.

[4] L. Breiman, J. Friedman, C. J. Stone, and R. A. Olshen. Classification and regression trees. CRC press, 1984.

[5] R. Caruana and A. Niculescu-Mizil. An empirical comparison of supervised learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the 23rd international conference on Machine learning, pages 161–168. ACM, 2006.

[6] B. Cestnik et al. Estimating probabilities: a crucial task in machine learning. In ECAI, volume 90, pages 147–149, 1990.

[7] O. Chapelle, E. Manavoglu, and R. Rosales. Simple and scalable response prediction for display advertising. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST), 5(4):61, 2015.

[8] T. Chen and C. Guestrin. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22Nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pages 785–794. ACM, 2016.

[9] M. Ferov and M. Modr `y. Enhancing lambdamart using oblivious trees. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.05610, 2016.

[10] J. Friedman, T. Hastie, and R. Tibshirani. Additive logistic regression: a statistical view of boosting. The annals of statistics, 28(2):337–407, 2000.

[11] J. Friedman, T. Hastie, and R. Tibshirani. The elements of statistical learning, volume 1. Springer series in statistics New York, 2001.

[12] J. H. Friedman. Greedy function approximation: a gradient boosting machine. Annals of statistics, pages 1189–1232, 2001.

[13] J. H. Friedman. Stochastic gradient boosting. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis, 38(4):367–378, 2002.

[14] A. Gulin, I. Kuralenok, and D. Pavlov. Winning the transfer learning track of yahoo!’s learning to rank challenge with yetirank. In Yahoo! Learning to Rank Challenge, pages 63–76, 2011.

[15] X. He, J. Pan, O. Jin, T. Xu, B. Liu, T. Xu, Y. Shi, A. Atallah, R. Herbrich, S. Bowers, et al. Practical lessons from predicting clicks on ads at facebook. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Workshop on Data Mining for Online Advertising, pages 1–9. ACM, 2014.

[16] G. Ke, Q. Meng, T. Finley, T. Wang, W. Chen, W. Ma, Q. Ye, and T.-Y. Liu. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 3149–3157, 2017.

[17] M. Kearns and L. Valiant. Cryptographic limitations on learning boolean formulae and finite automata. Journal of the ACM (JACM), 41(1):67–95, 1994.

[18] J. Langford, L. Li, and T. Zhang. Sparse online learning via truncated gradient. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 10(Mar):777–801, 2009.

[19] LightGBM. Categorical feature support. http://lightgbm.readthedocs.io/en/latest/Advanced-Topics.html#categorical-feature-support, 2017.

[20] LightGBM. Optimal split for categorical features. http://lightgbm.readthedocs.io/en/latest/Features.html#optimal-split-for-categorical-features, 2017.

[21] LightGBM. feature_histogram.cpp. https://github.com/Microsoft/LightGBM/blob/master/src/treelearner/feature_histogram.hpp, 2018.

[22] X. Ling, W. Deng, C. Gu, H. Zhou, C. Li, and F. Sun. Model ensemble for click prediction in bing search ads. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion, pages 689–698. International World Wide Web Conferences Steering Committee, 2017.

[23] Y. Lou and M. Obukhov. Bdt: Gradient boosted decision tables for high accuracy and scoring efficiency. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pages 1893–1901. ACM, 2017.

[24] L. Mason, J. Baxter, P. L. Bartlett, and M. R. Frean. Boosting algorithms as gradient descent. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 512–518, 2000.

[25] D. Micci-Barreca. A preprocessing scheme for high-cardinality categorical attributes in classifi-cation and prediction problems. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter, 3(1):27–32, 2001.

[26] B. P. Roe, H.-J. Yang, J. Zhu, Y. Liu, I. Stancu, and G. McGregor. Boosted decision trees as an alternative to artificial neural networks for particle identification. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section A: Accelerators, Spectrometers, Detectors and Associated Equipment, 543(2):577–584, 2005.

[27] L. Rokach and O. Maimon. Top–down induction of decision trees classifiers — a survey. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews), 35(4):476–487, 2005.

[28] D. B. Rubin. The bayesian bootstrap. The annals of statistics, pages 130–134, 1981.

[29] Q. Wu, C. J. Burges, K. M. Svore, and J. Gao. Adapting boosting for information retrieval measures. Information Retrieval, 13(3):254–270, 2010.

[30] K. Zhang, B. Schölkopf, K. Muandet, and Z. Wang. Domain adaptation under target and conditional shift. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 819–827, 2013.

[31] O. Zhang. Winning data science competitions. https://www.slideshare.net/ShangxuanZhang/winning-data-science-competitions-presented-by-owen-zhang,2015.

[32] Y. Zhang and A. Haghani. A gradient boosting method to improve travel time prediction. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 58:308–324, 2015.