End to end Active Object Tracking via Reinforcement Learning

Introduction

Object tracking has been a hot topic in recent years. It involves localization of an object in continuous video frames given an initial annotation in the first frame. The process normally consists of: 1) Taking an initial set of object detections 2) Creating and assigning unique ID for each of the initial detections. 3) Tracking those objects as they move around in the video frames, maintaining the assignment of unique IDs.

There are two types of object tracking. 1) Passive tracking 2) Active tracking.

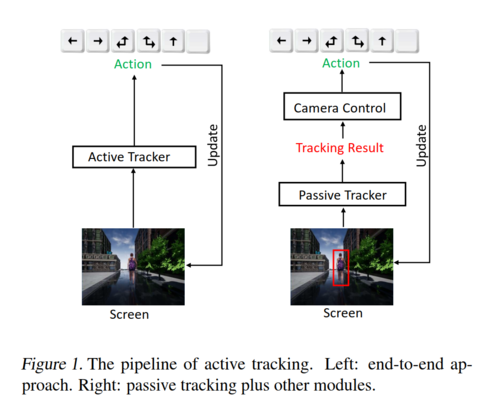

Much of the existing work has been done on passive tracking where it is assumed that the object of interest is always in the image scene so that there is no need to handle the camera control during tracking. Passive tracking though very useful is inapplicable in applications such as tracking performed by a mobile robot with a camera mounted or by a drone etc. Active tracking involves two sub tasks. 1) Object Tracking 2) Camera Control. It is difficult to jointly tune the pipeline with two separate sub tasks. Tracking may involve many human efforts for bounding box labelling. Camera control is non-trivial and can incur many expensive trial-and-errors happening in real world.

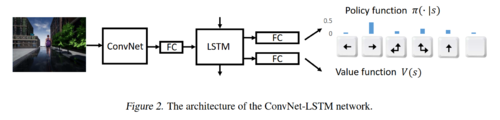

To address these challenges, in the paper an end-to-end active tracking solution via deep reinforcement learning is presented. More specifically ConvNet-LSTM network, taking raw video frames as input and outputting the camera movement actions. Virtual environment is used to simulate active tracking. In a virtual environment, an agent (i.e., the tracker) observes a state (a visual frame) from a first-person perspective and takes an action, and then the environment returns the updated state (next visual frame). AC3, a modern Reinforcement Learning algorithm, is adopted to train the agent, where a customized reward function is designed to encourage the agent to be closely following the object. Environment augmentation technique is used to boost the tracker’s generalization ability. The tracker trained in the Virtual Environment is then tested on a real-world video dataset to check the generalization ability of the model.

Related Work

Object Tracking

As explained earlier, object tracking can be done in two ways active and passive. Passive object tracking has gained much popularity because of its simpler problem setting. Many approaches have been proposed to overcome difficulties resulting from issues such as occlusion and illumination variation. a) In (Ross et al., 2008) subspace learning was adopted to update the appearance model of an object and integrated into a particle filter framework for object tracking. b) Babenko et al. (Babenko et al., 2009) employed multiple instance learning to track an object. c) Correlation filter based object tracking (Valmadre et al., 2017; Active object tracking additionally considers camera control compared with traditional object tracking. There exists not much research attention in the area of active tracking. Conventional solutions dealt with object tracking and camera control in separate components (Denzler & Paulus, 1994; Murray & Basu, 1994; Kim et al., 2005), but these solutions are difficult to tune. Our proposal is completely different from them as it tackles object tracking and camera control simultaneously in an end-to-end manner.

Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement Learning (RL) (Sutton & Barto, 1998) intends for a principled approach to temporal decision-making problems. In a typical RL framework, an agent learns from the environment a policy function that maps state to action at each discrete time step, where the objective is to maximize the accumulated rewards returned by the environment. Historically, RL has been successfully applied to inventory management, path planning, game playing, etc.

Approach

Virtual tracking scenes are generated for both training and testing. Asynchronous Actor-Critic Agents (A3C) model was used to train the tracker. RGB screen frame of the first-person perspective was chosen as the state for the study. The tracker observes a visual state and takes one action from the following set of 6 actions.

\[A = \{turn-left, turn-right, turn-left-and-move-forward,\\ turn-right-and-move-forward, move-forward, no-op\}\]

The action is processed by the environment, which returns to the agent the updated screen frame as well as the current reward.

Tracking Scenarios

Following two Virtual environment engines are used for the simulated training.

ViZDoom

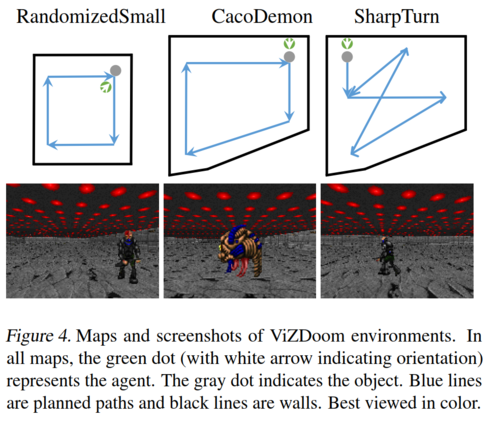

ViZDoom (Kempka et al., 2016; ViZ) is an RL research platform based on a 3D FPS video game called Doom. In ViZDoom, the game engine corresponds to the environment, while the video game player corresponds to the agent. The agent receives from the environment a state and a reward at each time step. In this study, customized ViZDoom maps are used. (see Fig. 4) composed of an object (a monster) and background (ceiling, floor, and wall). The monster walks along a pre-specified path programmed by the ACS script (Kempka et al., 2016), and the goal is to train the agent, i.e., the tracker, to follow closely the object.

Unreal Engine

Though convenient for research, ViZDoom does not provide realistic scenarios. To this end, Unreal Engine (UE) is adopted to construct nearly real-world environments. UE is a popular game engine and has a broad influence in the game industry. It provides realistic scenarios which can mimic real-world scenes. UnrealCV (Qiu et al., 2017) is employed in this study, which provides convenient APIs, along with a wrapper (Zhong et al., 2017) compatible with OpenAI Gym (Brockman et al., 2016), for interactions between RL algorithms and the environments constructed based on UE.

AC3 Algorithm

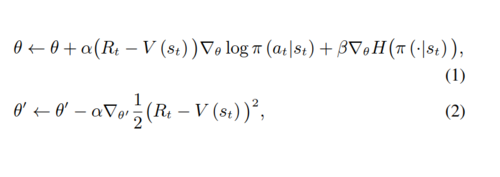

This paper employs the Asynchronous Actor-Critic Agents (AC3) algorithm for training the tracker. At time step t, st denotes the observed sate corresponding to the raw RGB frame. The action set is denoted by A of size A of size K = |A|. An action, at ∈ A, is drawn from a policy function distribution: at ∽π(·|st) ∈ RK, referred to as an Actor. The environment then returns a reward rt ∈ R according to a reward function rt = g(st). The updated state st+1 at next time step t+1 is subject to a certain but unknown state transition function st+1 = f(st, at), governed by the environment. Trace consisting of sequence of triplets can be observed. τ = {. . . , (st, at, rt) , (st+1, at+1, rt+1) , . . .} Meanwhile, V (st) ∈ R denotes the expected accumulated reward in the future given state st (referred to as Critic). The policy function π (·) and the value function V (·) are then jointly modeled by a neural network. Rewriting these as π(·|st; Ɵ) and V (st; Ɵ ′) with parameters Ɵ and Ɵ’ respectively. The parameters are learnt over trace τ by simultaneous stochastic policy gradient and value function regression.

Where Rt is a discounted sum of future rewards up to T time steps with a factor 0 < γ ≤ 1, α is the learning rate, H (·) is an entropy regularizer, and β is the regularizer factor.

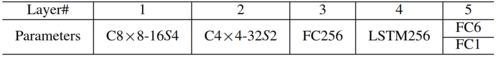

Network Architecture

The tracker is a ConvNet-LSTM neural network as shown in Fig. 2, where the architecture specification is given in the following table. The FC6 and FC1 correspond to the 6-action policy π (·|st) and the value V (st), respectively. The screen is resized to 84 × 84 × 3 RGB image as thea network input.

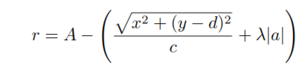

Reward Function

The reward function utilizes a two-dimensional local coordinate system (S). The x-axis points from the agent’s left shoulder to right shoulder, and the y-axis points perpendicular to the x-axis and points to the agent’s front. The origin is where is the agent is. System S is parallel to the floor. The object’s local coordinate (x,y) and orientation a with regard to the system S. The reward function is defined as follows.

Where A>0, c>0, d>0 and λ>0 are tuning parameters. The reward equation states that the maximum reward A is achieved when the object stands perfectly in front of the agent with distance d and exhibits no rotation. Environment Augmentation: To make the tracker generalize well, a environment augmentation technique is proposed for both virtual environments. For ViZDoom, (x,y,a) define the system state. For augmentation the initial system state is perturbed N times by editing the map with ACS script (Kempka et al., 2016), yielding a set of environments with varied initial positions and orientations {xi, yi, ai}iN=1 . Further flipping left-right the screen frame (and accordingly the left-right action) is allowed. As a result, 2N environments are obtained out of one environment. During A3C training, one of the 2N environments is randomly sampled at the beginning of every episode. For UE, an environment with a character/target following a fixed path is constructed. To augment the environment, random background objects are chosen. Every episode starts from the position, where the agent fails at the last episode. This makes the environment and starting point different from episode to episode, so the variations of the environment during training are augmented.

Experimental Results

Environment Setup

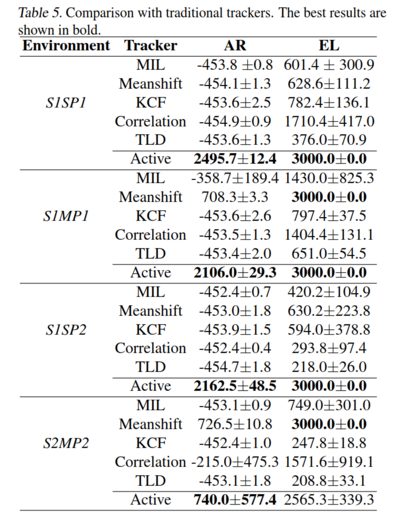

A set of environments are produced for both training and testing. For ViZDoom, a training map as in Fig. 4, left column is adopted. This map is then augmented with N = 21, leading to 42 environments that can be sampled from during training. For testing, 9 maps are made, some of which are shown in Fig. 4, middle and right columns. In all maps, the path of the target is pre-specified, indicated by the blue lines. However, it is worth noting that the object does not strictly follow the planned path. Instead, it sometimes randomly moves in a “zig-zag” way during the course, which is a built-in game engine behavior. This poses an additional difficulty to the tracking problem. For UE, an environment named Square with random invisible background objects is generated and a target named Stefani walking along a fixed path for training. For testing, another four environments named as Square1StefaniPath1 (S1SP1), Square1MalcomPath1 (S1MP1), Square1StefaniPath2 (S1SP2), and Square2MalcomPath2 (S2MP2) are made. As shown in Fig. 5, Square1 and Square2 are two different maps, Stefani and Malcom are two characters/targets, and Path1 and Path2 are different paths. Note that, the training environment Square is generated by hiding some background objects in Square1. For both ViZDoom and UE, an episode is terminated when either the accumulated reward drops below a threshold or the episode length reaches a maximum number. In these experiments, the reward threshold is set as -450 and the maximum length as 3000, respectively.

Metric

Two metrics are employed for the experiments. Accumulated Reward (AR) and Episode Length (EL). AR is like Precision in the conventional tracking literature. EL roughly measures the duration of good tracking.

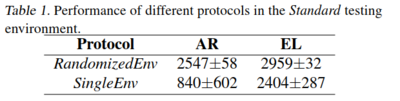

Results

Two training protocols were followed namely RandomizedEnv(with augmentation) and SingleEnv(with the augmentation technique). However, only the results for RandomizedEnv are reported in the paper. There is only one table specifying the result from SingleEnv training which shows that it performs worse than the RandomizedEnv training. The variability in the test results is very high for the non-augmented training case.

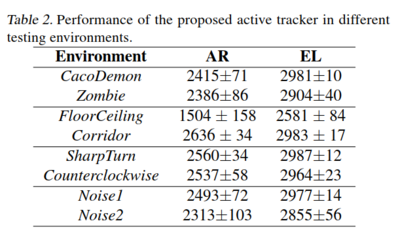

The testing environments results are reported in Tab. 2.

Following are the findings from the testing results: 1. The tracker generalizes well in the case of target appearance changing (Zombie, Cacodemon). 2. The tracker is insensitive to background variations such as changing the ceiling and floor (FloorCeiling) or placing additional walls in the map (Corridor). 3. The tracker does not lose a target even when the target takes several sharp turns (SharpTurn). Note that in conventional tracking, the target is commonly assumed to move smoothly. 4. The tracker is insensitive to a distracting object (Noise1) even when the “bait” is very close to the path (Noise2).

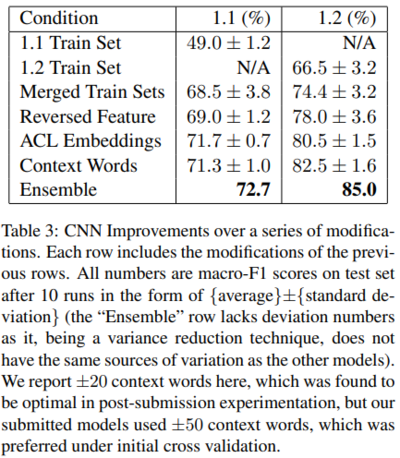

The proposed tracker is compared against several of the conventional trackers with PID like module for camera control to simulate active tracking. The results are displayed in Tab. 3.

The camera control module is implemented such that in the first frame, a manual bounding box must be given to indicate the object to be tracked. For each subsequent frame, the passive tracker then predicts a bounding box which is passed to the Camera Control module. A comparison is made between the two subsequent bounding boxes as per the algorithm and action decision is made. The results show that the proposed solution outperforms the simulated active tracker. The simulated trackers lost their targets soon. The Meanshift tracker works well when there is no camera shift between continuous frames. Both KCF and Correlation trackers seem not capable of handling such a large camera shift, so they do not work as well as the case in passive tracking. The MIL tracker works reasonably in the active case, while it easily drifts when the object turns suddenly. Testing in the UE environment is tabulated in Table 5.

1. Comparison between S1SP1 and S1MP1 shows that the tracker generalizes well even when the model is trained with target Stefani, revealing that it does not overfit to a specialized appearance. 2. The active tracker performs well when changing the path (S1SP1 versus S1SP2), demonstrating that it does not act by memorizing specialized path. 3. When the map is changed, target, and path at the same time (S2MP2), though the tracker could not seize the target as accurately as in previous environments (the AR value drops), it can still track objects robustly (comparable EL value as in previous environments), proving its superior generalization potential. 4. In most cases, the proposed tracker outperforms the simulated active tracker, or achieves comparable results if it is not the best. The results of the simulated active tracker also suggest that it is difficult to tune a unified camera-control module for them, even when a long-term tracker is adopted (see the results of TLD).

Real world active tracking: To test and evaluate the tracker in real world scenarios, the network trained on UE environment is tested on few videos from the VOT dataset.

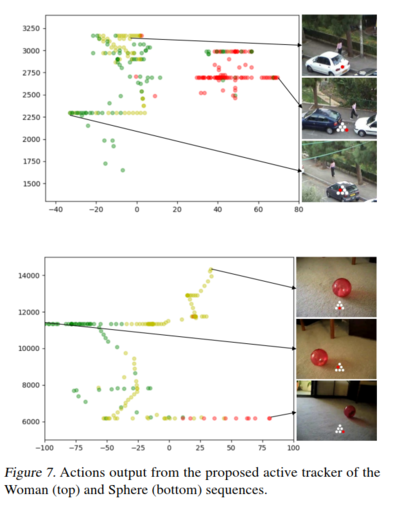

Fig. 7 shows the output actions for two video clips named Woman and Sphere, respectively. The horizontal axis indicates the position of the target in the image, with a positive (negative) value meaning that a target in the right (left) part. The vertical axis indicates the size of the target, i.e., the area of the ground truth bounding box. Green and red dots indicate turn-left/turn-left-and-move-forward and turn-right/turn-right-and-move-forward actions, respectively. Yellow dots represent No-op action. As the figure show, 1) When the target resides in the right (left) side, the tracker tends to turn right (left), trying to move the camera to “pull” the target to the center. 2) When the target size becomes bigger, which probably indicates that the tracker is too close to the target, the tracker outputs no-op actions more often, intending to stop and wait the target to move farther.

Conclusion

In the paper, an end-to-end active tracker via deep reinforcement learning is proposed. Unlike conventional passive trackers, the proposed tracker is trained in simulators, saving the efforts of human labeling or trail-and-errors in real-world. It shows good generalization to unseen environments. The tracking ability can potentially transfer to real-world scenarios.

Critique

The paper presents a solution for active tracking using reinforcement learning. The tracker trained using environment augmentation performs better than the one trained without augmentation. This is true in both the ViZDoom and UE environment. The reward function looks intuitive for the task at hand which is object tracking. Within the virtual environment ViZDoom though used for training and testing seems to have little or no generalizability in real world scenarios. The maps in ViZDoom itself are very simple. The comparison presented in the paper for the ViZDoom testing with changes in the environment parameters look positive, but the relatively simple nature of the environment needs to be considered. Also, when the floor is replaced by the ceiling the tracker performs worst in comparison to the other cases in the table, which seems to indicate that the floor and ceiling parameters are somewhat learnt overfitted in the model. The tracker trained in UE environment is tested against simulated trackers. The results show that the proposed solution performs better than the simulated trackers. However, since the trackers are simulated, and the camera control algorithm is designed for this specific comparison and further testing is required for benchmarking. The real-world challenges of intensity variation, camera details, control signals though out of scope of the current paper, still need to be considered while discussing the generalizability of the model to real world scenarios. The results on the real-world videos show a positive result towards the generalizability of the models in real world settings. The overall approach presented in the paper is intuitive and the results look promising.