Dialog-based Language Learning

Note: Do not start editing until 8th Nov 2017

This page will be published for editing by EOD 7th Nov 2017 This page is a summary for NIPS 2016 paper - Dialog-based Language Learning by Jason Weston[1].

Introduction

One of the ways humans learn language, especially second language or language learning by students, is by communication and getting its feedback. However, most existing research in Natural Language Understanding has focused on supervised learning from fixed training sets of labeled data. This kind of supervision is not realistic of how humans learn, where language is both learned by, and used for, communication. When humans act in dialogs (i.e., make speech utterances) the feedback from other human’s responses contain very rich information. This is perhaps most pronounced in a student/teacher scenario where the teacher provides positive feedback for successful communication and corrections for unsuccessful ones.

This paper is about dialog-based language learning, where supervision is given naturally and implicitly in the response of the dialog partner during the conversation. This paper is a step towards the ultimate goal of being able to develop an intelligent dialog agent that can learn while conducting conversations. Specifically this paper explores whether we can train machine learning models to learn from dialog.

Contributions of this paper

- Introduce a set of tasks that model natural feedback from a teacher and hence assess the feasibility of dialog-based language learning.

- Evaluated some baseline models on this data and compared them to standard supervised learning.

- Introduced a novel forward prediction model, whereby the learner tries to predict the teacher’s replies to its actions, which yields promising results, even with no reward signal at all

Background on Memory Networks

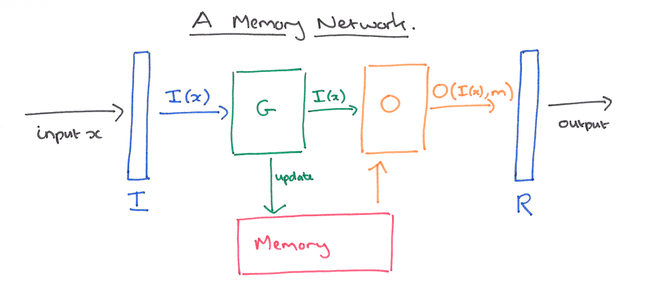

A memory network combines learning strategies from the machine learning literature with a memory component that can be read and written to.

The high-level view of a memory network is as follows:

- There is a memory, m, an indexed array of objects (e.g. vectors or arrays of strings).

- An input feature map I, which converts the incoming input to the internal feature representation

- A generalization component G which updates old memories given the new input.

- An output feature map O, which produces a new output in the feature representation space given the new input and the current memory state.

- A response component R which converts the output into the response format desired – for example, a textual response or an action.

I,G,O and R can all potentially be learned components and make use of any ideas from the existing machine learning literature.

In question answering systems for example, the components may be instantiated as follows:

- I can make use of standard pre-processing such as parsing, coreference, and entity resolution. It could also encode the input into an internal feature representation by converting from text to a sparse or dense feature vector.

- The simplest form of G is to introduce a function H which maps the internal feature representation produced by I to an individual memory slot, and just updates the memory at H(I(x)).

- O Reads from memory and performs inference to deduce the set of relevant memories needed to perform a good response.

- R would produce the actual wording of the question answer based on the memories found by O. For example, R could be an RNN conditioned on the output of O

When the components I,G,O, & R are neural networks, the authors describe the resulting system as a Memory Neural Network (MemNN). They build a MemNN for QA (question answering) problems and compare it to RNNs (Recurrent Neural Network) and LSTMs (Long Short Term Memory RNNs) and find that it gives superior performance.

Related Work

Usefulness of feedback in language learning: P. K. Kuhl et al [2004] has emphasized the usefulness of social interaction and natural infant directed conversations. Several studies, M. A. Bassiri et al [2011], R. Higgins et al [2002], A. S. Latham et al [1997], M. G. Werts et al [1995] has shown that feedback is especially useful in second language learning and learning by students.

Supervised learning from dialogs using neural models: A. Sordoni et al [2015] has used neural networks for response generation that can be trained end to end on large quantities of unstructured Twitter conversations. However this does not incorporate feedback from dialog partner during real time conversation

Reinforcement learning: Reinforcement learning works on dialogs, often consider reward as the feedback model rather than exploiting the dialog feedback per se.

Forward prediction models: Although forward prediction models, have been used in other applications like learning eye-tracking, controlling robot arms and vehicles, it has not been used for dialog.

Dialog-based Supervision tasks

For testing their models, the authors chose two datasets (i) the single supporting fact problem from the bAbI datasets [23] which consists of short stories from a simulated world followed by questions; and (ii) the MovieQA dataset [3] which is a large-scale dataset (∼ 100k questions over ∼ 75k entities) based on questions with answers in the open movie database (OMDb)

However, since these datasets were not designed to model the supervision from dialogs, the authors modified them to create 10 supervision task types on these datasets. These are:

- Task 1: Imitating an Expert Student: In Task 1 the dialogs take place between a teacher and an expert student who gives semantically coherent answers. Hence, the task is for the learner to imitate that expert student, and become an expert themselves

- Task 2: Positive and Negative Feedback: In Task 2, when the learner answers a question the teacher then replies with either positive or negative feedback. In our experiments the subsequent responses are variants of “No, that’s incorrect” or “Yes, that’s right”. In the datasets we build there are 6 templates for positive feedback and 6 templates for negative feedback, e.g. ”Sorry, that’s not it.”, ”Wrong”, etc. To separate the notion of positive from negative (otherwise the signal is just words with no notion that yes is better than no) we assume an additional external reward signal that is not part of the text

- Task 3: Answers Supplied by Teacher: In Task 3 the teacher gives positive and negative feedback as in Task 2, however when the learner’s answer is incorrect, the teacher also responds with the correction. For example if “where is Mary?” is answered with the incorrect answer “bedroom” the teacher responds “No, the answer is kitchen”’

- Task 4: Hints Supplied by Teacher: In Task 4, the corrections provided by the teacher do not provide the exact answer as in Task 3, but only a useful hint. This setting is meant to mimic the real life occurrence of being provided only partial information about what you did wrong.

- Task 5: Supporting Facts Supplied by Teacher: In Task 5, another way of providing partial supervision for an incorrect answer is explored. Here, the teacher gives a reason (explanation) why the answer is wrong by referring to a known fact that supports the true answer that the incorrect answer may contradict.

- Task 6: Partial Feedback: Task 6 considers the case where external rewards are only given some of (50% of) the time for correct answers, the setting is otherwise identical to Task 3. This attempts to mimic the realistic situation of some learning being more closely supervised (a teacher rewarding you for getting some answers right) whereas other dialogs have less supervision (no external rewards). The task attempts to assess the impact of such partial supervision.

- Task 7: No Feedback: In Task 7 external rewards are not given at all, only text, but is otherwise identical to Tasks 3 and 6. This task explores whether it is actually possible to learn how to answer at all in such a setting.

- Task 8: Imitation and Feedback Mixture: Task 8 combines Tasks 1 and 2. The goal is to see if a learner can learn successfully from both forms of supervision at once. This mimics a child both observing pairs of experts talking (Task 1) while also trying to talk (Task 2).

- Task 9: Asking For Corrections: The learner will ask questions to the teacher about what it has done wrong. Task 9 tests one of the most simple instances, where asking “Can you help me?” when wrong obtains from the teacher the correct answer.

- Task 10: Asking for Supporting Facts: A less direct form of supervision for the learner after asking for help is to receive a hint rather than the correct answer, such as “A relevant fact is John moved to the bathroom” when asking “Can you help me?”. This is thus related to the supervision in Task 5 except the learner must request help

For each task a fixed policy is considered for performing actions (answering questions) which gets questions correct with probability πacc (i.e. the chance of getting the red text correct in Figs. 1 and 2). We thus can compare different learning algorithms for each task over different values of πacc (0.5, 0.1 and 0.01). In all cases a training, validation and test set is provided.

Learning models

This work evaluates four possible learning strategies for each of the 10 tasks: imitation learning, reward-based imitation, forward prediction, and a combination of reward-based imitation and forward prediction

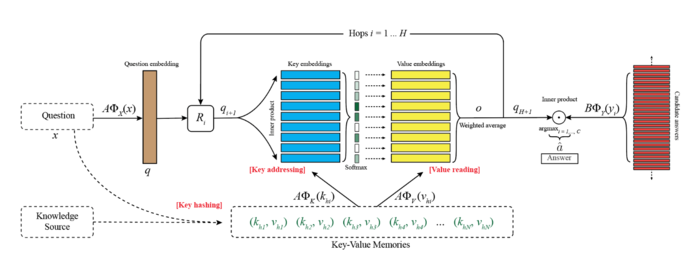

All of these approaches with the same model architecture: an end-to-end memory network (MemN2N) [20], which has been used as a baseline model for exploring differing modes of learning.

The input is the last utterance of the dialog, x, as well as a set of memories (context) (c1, . . . , cN ) which can encode both short-term memory, e.g. recent previous utterances and replies, and long-term memories, e.g. facts that could be useful for answering questions. The context inputs ci are converted into vectors mi via embeddings and are stored in the memory. The goal is to produce an output aˆ by processing the input x and using that to address and read from the memory, m, possibly multiple times, in order to form a coherent reply. In the figure the memory is read twice, which is termed multiple “hops” of attention.

In the first step, the input x is embedded using a matrix A of size d × V where d is the embedding dimension and V is the size of the vocabulary, giving q = Ax, where the input x is as a bag-of words vector. Each memory ci is embedded using the same matrix, giving mi = Aci . The output of addressing and then reading from memory in the first hop is:

- Add eqn here

Here, the match between the input and the memories is computed by taking the inner product followed by a softmax, yielding p 1 , giving a probability vector over the memories. The goal is to select memories relevant to the last utterance x, i.e. the most relevant have large values of p 1 i . The output memory representation o1 is then constructed using the weighted sum of memories, i.e. weighted by p 1 . The memory output is then added to the original input, u1 = R1(o1 + q), to form the new state of the controller, where R1 is a d × d rotation matrix2 . The attention over the memory can then be repeated using u1 instead of q as the addressing vector, yielding:

- add eqn here

The controller state is updated again with u2 = R2(o2 + u1), where R2 is another d × d matrix to be learnt. In a two-hop model the final output is then defined as:

- Add eqn here

where there are C candidate answers in y. In our experiments C is the set of actions that occur in the training set for the bAbI tasks, and for MovieQA it is the set of words retrieved from the KB.