Annotating Object Instances with a Polygon RNN

Summary of the CVPR '17 best paper

The presentation video of paper is available here[1].

Introduction

If a snapshot of an image is given to a human, how will he/she describe a scene? He/she might identify that there is a car parked near the curb, or that the car is parked right beside a street light. This ability to decompose objects in scenes into separate entities is key to understanding what is around us and it helps to reason about the behavior of objects in the scene.

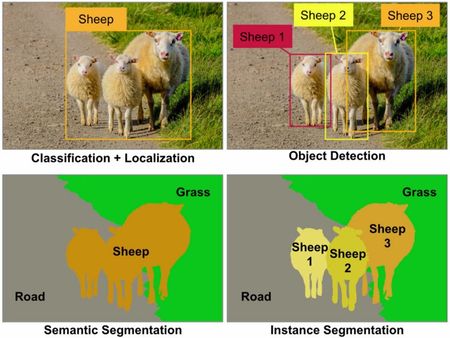

Automating this process is a classic computer vision problem and is often termed "object detection". There are four distinct levels of detection (refer to Figure 1 for a visual cue):

1. Classification + Localization: This is the most basic method that detects whether an object is either present or absent in the image and then identifies the position of the object within the image in the form of a bounding box overlayed on the image.

2. Object Detection: The classic definition of object detection points to the detection and localization of multiple objects of interest in the image. The output of the detection is still a bounding box overlayed on the image at the position corresponding to the location of the objects in the image.

3. Semantic Segmentation: This is a pixel level approach, i.e., each pixel in the image is assigned to a category label. Here, there is no difference between instances; this is to say that there are objects present from three distinct categories in the image, without tracking or reporting the number of appearances of each instance within a category.

4. Instance Segmentation: The goal, here, is to not only to assign pixel-level categorical labels, but also to identify each entity separately as sheep 1, sheep 2, sheep 3, grass, and so on.

Motivation

Semantic segmentation helps us achieve a deeper understanding of images than image classification or object detection. Over and above this, instance segmentation is crucial in applications where multiple objects of the same category are to be tracked, especially in autonomous driving, mobile robotics, and medical image processing. This paper deals with a novel method to tackle the instance segmentation problem pertaining specifically to the field of autonomous driving, but shown to generalize well in other fields such as medical image processing.

Most of the recent approaches to on instance segmentation are based on deep neural networks and have demonstrated impressive performance. Given that these approaches require a lot of computational resources and that their performance depends on the amount of accessible training data, there has been an increase in the demand to label/annotate large-scale datasets. This is both expensive and time-consuming. Thus, the main goal of the paper is to enable semi-automatic annotation of object instances.

Most of the datasets available pass through a stage where annotators manually outline the objects with a closed polygon. Polygons allow annotation of objects with a small number of clicks (30 - 40) compared to other methods; this approach works as the silhouette of an object is typically connected without holes. Thus, the authors' intuition behind the success of this method is the sparse nature of these polygons that allow representation of an object through a cluster of pixels rather than a pixel level description.

Related Works

The related works are related to the fields of semi-automatic image annotation and object instance segmentation.

The critical advances in the field of semi-automatic annotation are as follows:

1) Some researchers use scribbles as seeds to model the appearance of foreground and background.

2) Other works use multiple scribbles on the object and exploit motion cues to annotate an object in a video.

3) Scribbles are also used to train CNNs for semantic image segmentation.

4) Some methods exploit annotations in the form of 2D bounding boxes and perform per-pixel labeling with foreground/background models using EM.

The following are the critical advances in the field of Object instance segmentation:

1) Most of the approaches operate on pixel-level and exploit a CNN inside a box or a patch to perform the labeling.

2) Some approaches aim to produce a polygon around an object. These approaches start by detecting edge fragments and find an optimal cycle that links the edges into a coherent region.

3) One particular work uses superpixels in the form of small polygons which is combined into object regions with the aim to label aerial images.

Model

As an input to the model, an annotator or perhaps another neural network provides a ground-truth bounding box containing an object of interest and the model auto-generates a polygon outlining the object instance using a Recurrent Neural Network which they call: Polygon-RNN.

The RNN model predicts the vertices of the polygon at each time step given a CNN representation of the image, the last two time steps, and the first vertex location. The location of the first vertex is defined differently and will be defined shortly. The information regarding the previous two-time steps helps the RNN create a polygon in a specific direction and the first vertex provides a cue for loop closure of the polygon edges.

The polygon is parametrized as a sequence of 2D vertices and it is assumed that the polygon is closed. In addition, the polygon generation is fixed to follow a clockwise orientation since there are multiple ways to create a polygon given that it is cyclic structure. However, the starting point of the sequence is defined so that it can be any of the vertices of the polygon.

Architecture

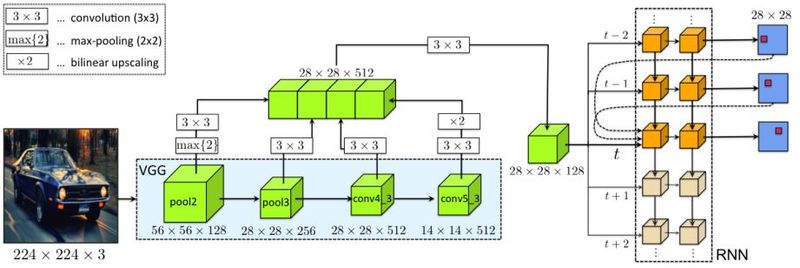

There are two primary networks at play: 1. CNN with skip connections, and 2. One-to-many type RNN.

1. CNN with skip connections:

The authors have adopted the VGG16 feature extractor architecture with a few modifications pertaining to the preservation of feature fused together in a tensor that can feed into the RNN (refer to Figure 2). Namely, the last max-pool layer present in the VGG16 CNN has been removed. The image fed into the CNN is pre-shrunk to a 224x224x3 tensor(3 being the Red, Green, and Blue channels). The image passing through 2 pooling layers with 128 and 2 convolutional layers. At each of these four steps, the idea is to have a width of 512 and so the output tensor at pool2 is convolved with 4 3x3x128 filters and the output tensor at pool3 is convolved with 2 3x3x256 filters. The skip connections from the four layers allow the CNN to extract low-level edge and corner features as well as boundary/semantic information about the instances. Finally, a 3x3 convolution applied along with a ReLU non-linearity results in a 28x28x128 tensor that contains semantic information pertinent to the image frame and is taken as an input by the RNN.

2. RNN - 2 Layer ConvLSTM

The RNN is employed to capture information about the previous vertices in the time-series. Specifically, a Convolutional LSTM is used as a decoder. The ConvLSTM allows preservation of the spatial information in 2D and reduces the number of parameters compared to a Fully Connected RNN. The polygon is modeled with a kernel size of 3x3 and 16 channels outputting a vertex at each time step. The ConvLSTM gets as input a tensor step t which concatenates 4 features: the CNN feature representation of the image, one-hot encodingof the previous predicted vertex and the vertex predicted from two time steps ago, as well as the one-hot encoding of the first predicted vertex.

The authors have treated the vertex prediction task as a classification task in that the location of the vertices is through a one-hot representation of dimension DxD + 1 (D chosen to be 28 by the authors in tests). The one additional dimension is the storage cue for loop closure for the polygon. Given that, the one-hot representation of the two previously predicted vertices and the first vertex are taken in as an input, a clockwise (or for that reason any fixed direction) direction can be forced for the creation of the polygon. Coming back to the prediction of the first vertex, this is done through further modification of the CNN by adding two DxD layers with one branch predicting object instance boundaries while the other takes in this output as well as the image features to predict the first vertex.

Training

The training of the model is done as follows:

1. Cross-entropy is used for the RNN cost function.

2. Instead of Stochastic Gradient Descent, Adam is used for optimization: batch size = 8, learning rate = 1e^-4 (learning rate decays after 10 epochs by a factor of 10)

3. For the first vertex prediction, the modified CNN mentioned previously, is trained using a multi-task cost function.

The reported time for training is one day on a Nvidia Titan-X GPU.

Human Annotator in the Loop

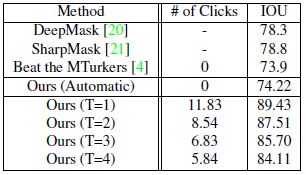

The model allows for the prediction at a given time step to be corrected and this corrected vertex is then fed into the next time step of the RNN, effectively rejecting the network predicted vertex. This has the simple effect of putting the model "back on the right track". The typical inference time as quoted by the paper is 250ms per object.

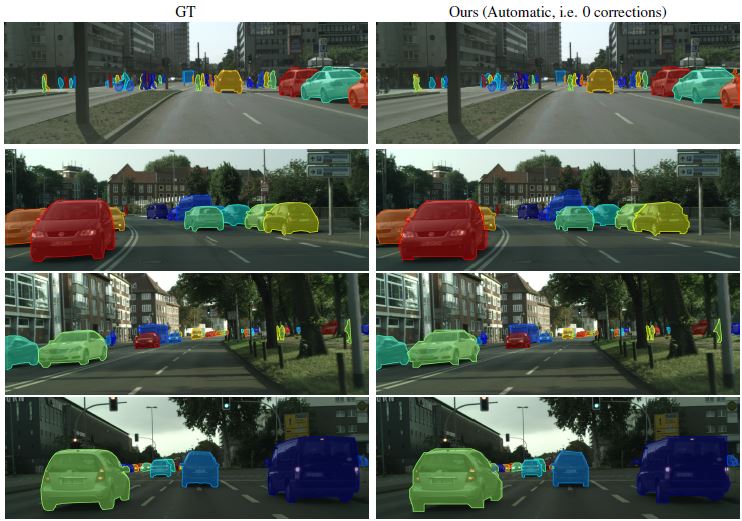

Results

The evaluation of the model performance was conducted based on the Cityscapes and KITTI Datasets. The standard Intersection over Union (IoU) measure is used for comparison. The calculation for IoU takes both the predicted and ground-truth object boundaries. The intersection (area contained in both boundaries at once) is divided by the union (the area contained by at least one, or both, of the boundaries). A low score of this metric would mean that there is little overlap between the boundaries, or large areas on non-overlap, and a score of 1.0 would indicate that the two boundaries contain the same area.

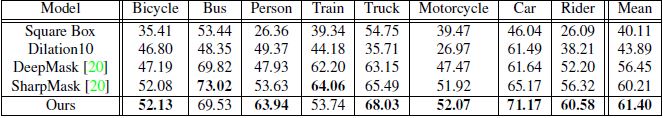

Compared to other instance segmentation techniques, the Polygon-RNN method performs significantly better in the person, car, and rider categories and above average in other categories. In addition, with the help of the annotator, the speedup factor was 7.3 times with under 5 clicks which the authors claim is the main advantage of this method.

In addition, most of the comparisons with human annotators show that the method is at par with human-level annotation.

-

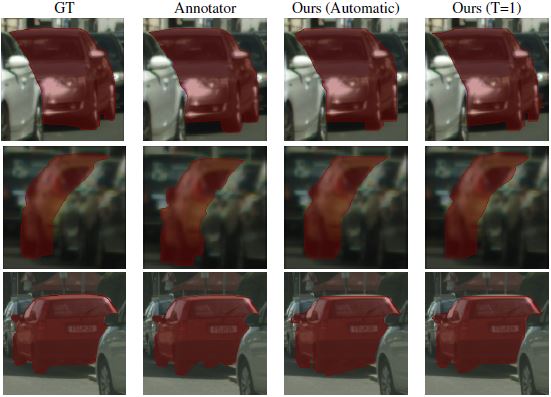

Figure 3: Qualitative results without human annotator in the loop.

-

Figure 4: Qualitative results: comparison with human annotator.

Conclusion

The important conclusions from this paper are:

1. The paper presented a powerful generic annotation tool that works on different unseen datasets.

2. Significant improvement in annotation time can be achieved with the Polygon-RNN method itself (speed-up factor of 4.74).

3. However, the flexibility of having inputs from a human annotator helps increase the IoU for a certain range of clicks.

4. The model architecture has a down-sampling factor of 16 and the final output resolution and accuracy is sensitive to object size.

5. Another downside of the model architecture is that training time is increased due to the training of the CNN for the first vertex.

Critique

1. This paper requires training of an entire CNN for the first vertex and is inefficient in that sense as it introduces additional parameters adding to the computation time and resource demand.

2. The method outperforms other methods only in the three categories mentioned but isn't a significant improvement in other categories.

3. The baseline methods have an upper hand compared to this model when it comes to larger objects since the nature of the down-scaled structure adopted by this model.

4. With the human annotator in the loop, the model speeds up the process of annotation by over 7 times which is perhaps a big cost and time cutting improvement for companies.

5. In terms of future work, elimination of the additional CNN for the first vertex as well as an enhanced architecture to remain insensitive to the size of the object to be annotated should be implemented.