GradientLess Descent: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

Let <math display="inline">B_1, B_2 \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n</math> be balls of radii <math display="inline">r_1, r_2</math>. Let <math display="inline">\ell</math> be the distance between the centres. If <math display="inline">r_1 \in \left[ \frac{\ell}{2 \sqrt{n}} , \frac{\ell}{\sqrt{n}} \right]</math> and <math display="inline">r_2 \geq \ell - \frac{\ell}{4n}</math>, then <math display="inline">\lambda (B_1 \cap B_2) \geq c_n \lambda (B_1)</math>, where <math display="inline">c_n \geq \frac{1}{4}</math>. | Let <math display="inline">B_1, B_2 \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n</math> be balls of radii <math display="inline">r_1, r_2</math>. Let <math display="inline">\ell</math> be the distance between the centres. If <math display="inline">r_1 \in \left[ \frac{\ell}{2 \sqrt{n}} , \frac{\ell}{\sqrt{n}} \right]</math> and <math display="inline">r_2 \geq \ell - \frac{\ell}{4n}</math>, then <math display="inline">\lambda (B_1 \cap B_2) \geq c_n \lambda (B_1)</math>, where <math display="inline">c_n \geq \frac{1}{4}</math>. | ||

Using this theorem about random searches in high dimensions, we can prove the correctness of our algorithm. | |||

'''Theorem 2''' | |||

For any <math display="inline">x \in K</math> such that <math display="inline">\frac{3}{5Q} ||x - x^*|| \in [C_1, C_2]</math>, we can find integers <math display="inline">0 \leq k_1, k_2 < \log \frac{C_2}{C_1}</math> such that if <math display="inline">r = 2^{k_1}C_1</math> or <math display="inline">r = 2^{-k_2}C_2</math>, then a sample <math display="inline">y</math> from the uniform distribution on <math display="inline">B_x = B\left( x, \frac{r}{\sqrt{n}} \right) </math> satisfies | |||

\begin{align*} | |||

f(y) - f(x^*) \leq (f(x) - f(x^*)) \left( 1- \frac{1}{5nQ} \right) | |||

\end{align*} | |||

with probability at least <math display="inline">\frac{1}{4}</math>. | |||

Notice how the second theorem implies that with probability a quarter, <math display="inline">f(y)</math> is closer to the optimum than <math display="inline">f(x)</math> is. | |||

For proofs of these theorems, please watch my talk. | |||

Revision as of 12:34, 2 November 2020

Introduction

Motivation and Set-up

A general optimisation question can be formulated by asking to minimise an objective function [math]\displaystyle{ f : \mathbb{R}^n \to \mathbb{R} }[/math], which means finding: \begin{align*} x^* = \mathrm{argmin}_{x \in \mathbb{R}^n} f(x) \end{align*}

Depending on the nature of [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math], different settings may be considered:

- Convex vs non-convex objective functions;

- Differentiable vs non-differentiable objective functions;

- Allowed function or gradient computations;

- Noisy/Stochastic oracle access.

For the purpose of this paper, we consider convex smooth objective noiseless functions, where we have access to function computations but not gradient computations. This class of functions is quite common in practice; for instance, they make special appearances in the reinforcement learning literature.

To be even more precise, in our context we let [math]\displaystyle{ K \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n }[/math] be compact [math]\displaystyle{ f : K \to \mathbb{R} }[/math] be [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math]-smooth and [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math]-strongly convex.

Definition 1

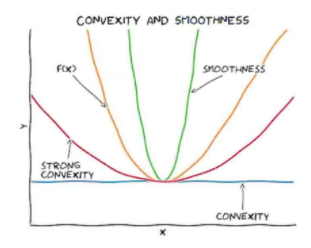

A convex continuously differentiable function [math]\displaystyle{ f : K \to \mathbb{R} }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math]-strongly convex for [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha \gt 0 }[/math] if \begin{align*} f(y) \geq f(x) + \left\langle \nabla f(x), y-x\right\rangle + \frac{\alpha}{2} ||y - x||^2 \end{align*} for all [math]\displaystyle{ x,y \in K }[/math]. It is called [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math]-smooth for [math]\displaystyle{ \beta \gt 0 }[/math] if \begin{align*} f(y) \leq f(x) + \left\langle \nabla f(x), y-x\right\rangle + \frac{\beta}{2} || y - x||^2 \end{align*} for all [math]\displaystyle{ x,y \in K }[/math]

We remark that if [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is twice continuously differentiable, this is simply equivalent to the eigenvalues of the Hessian matrix [math]\displaystyle{ Hf }[/math] being bounded between [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math]. Further intuition can be gained from the image below, showing how such a function can be contained within quadratic bounds.

In convex analysis, one usually says that a function has condition number [math]\displaystyle{ Q }[/math] if it is both [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math]-strongly convex, and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math]-smooth, and [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\beta}{\alpha} \leq Q }[/math]. The authors of this paper consider the more general case where [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is a monotone transformation of a [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math]-strongly convex and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math]-smooth function; for simplicity and transparency, we shall not consider these extensions here, but shall note that their proofs are quite elementary.

Zeroth-Order Optimisation

In zeroth-order optimisation, we are interested in minimising a function without computing its derivatives. This is important in many practical applications in which derivatives may not be available or they may be difficult to compute, such as:

- Combinatorial (i.e. discrete) optimisation

- Instances of non-analytic loss functions (e.g. hyperparameter tuning)

- Adversarial attacks

- Reinforcement learning

Curiously, a large amount of this approach focuses on approximating gradients and then using first-order optimisation algorithms.

This paper presents a purely gradientless algorithm, proposes a geometric approach to analyse the algorithm, and proves a [math]\displaystyle{ O( k Q \log (n / \epsilon )) }[/math] convergence bound.

GradientLess Descent Algorithm

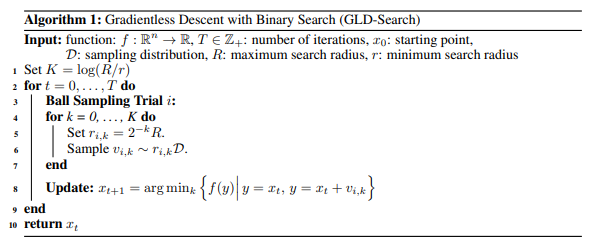

The proposed algorithm is given in the picture below.

Observe that at each step, we perform binary search over several concentric circles and randomly sample points, in the hopes that if we take a small step in a random direction this will reduce the value of the objective function.

Proof of correctness

The correctness of this algorithm hinges on two observations. The first one is about the volume of the intersection of high-dimensional balls; we call this intersection a hyperspherical cap.

Theorem 1

Let [math]\displaystyle{ B_1, B_2 \subseteq \mathbb{R}^n }[/math] be balls of radii [math]\displaystyle{ r_1, r_2 }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \ell }[/math] be the distance between the centres. If [math]\displaystyle{ r_1 \in \left[ \frac{\ell}{2 \sqrt{n}} , \frac{\ell}{\sqrt{n}} \right] }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ r_2 \geq \ell - \frac{\ell}{4n} }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda (B_1 \cap B_2) \geq c_n \lambda (B_1) }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ c_n \geq \frac{1}{4} }[/math].

Using this theorem about random searches in high dimensions, we can prove the correctness of our algorithm.

Theorem 2

For any [math]\displaystyle{ x \in K }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{3}{5Q} ||x - x^*|| \in [C_1, C_2] }[/math], we can find integers [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \leq k_1, k_2 \lt \log \frac{C_2}{C_1} }[/math] such that if [math]\displaystyle{ r = 2^{k_1}C_1 }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ r = 2^{-k_2}C_2 }[/math], then a sample [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] from the uniform distribution on [math]\displaystyle{ B_x = B\left( x, \frac{r}{\sqrt{n}} \right) }[/math] satisfies \begin{align*} f(y) - f(x^*) \leq (f(x) - f(x^*)) \left( 1- \frac{1}{5nQ} \right) \end{align*} with probability at least [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{4} }[/math].

Notice how the second theorem implies that with probability a quarter, [math]\displaystyle{ f(y) }[/math] is closer to the optimum than [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math] is.

For proofs of these theorems, please watch my talk.