stat441w18/Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification: Difference between revisions

| Line 184: | Line 184: | ||

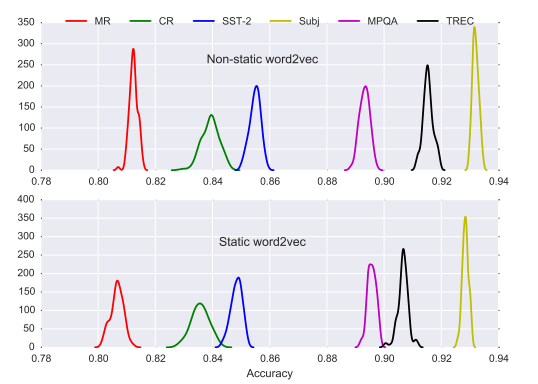

[[File:density.png|600px|thumb|center|Density curve of accuracy using static and non-static word2vec-CNN | [[File:density.png|600px|thumb|center|Density curve of accuracy using static and non-static word2vec-CNN | ||

(Zhang, Y. Wallace, B. 2016)]] | |||

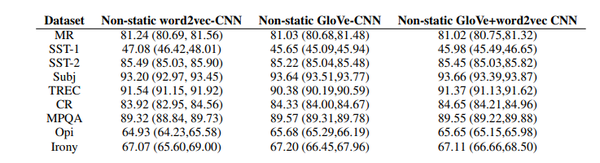

How does using different word vector representations effect the results? | |||

[[File:glove vs word2vec.png|600px|thumb|center|Glove vs. word2vec on non-static CNN | |||

(Zhang, Y. Wallace, B. 2016)]] | (Zhang, Y. Wallace, B. 2016)]] | ||

Revision as of 18:21, 12 March 2018

Presented by

1. Ben Schwarz

2. Cameron Miller

3. Hamza Mirza

4. Pavle Mihajlovic

5. Xiaowen Shi

6. Yitian Wu

7. Zekai Shao

Introduction

Deep learning is being used widely in visual and speech recognition and Natural Language Processing (NLP) has already became an important topic of research in this field. Most of the work performed for this revolves around learning word embeddings and completing compositions over the learned material.

The work for this paper obtained unsupervised word to vectors that were trained on the 100 billion publicly available words on google news. These words were then used to train a simple CNN with one layer of convolution. The simple model achieved excellent results and even with just little tuning of the hyper parameters. This suggests that pre-trained vectors can be effectively utilized for classification tasks.

The simple model was tested on various datasets such as movie reviews, Stanford Sentiment Treebank and customer reviews. Despite its limitations, the results were competitive to more complex models that use pooling schemes.

Model

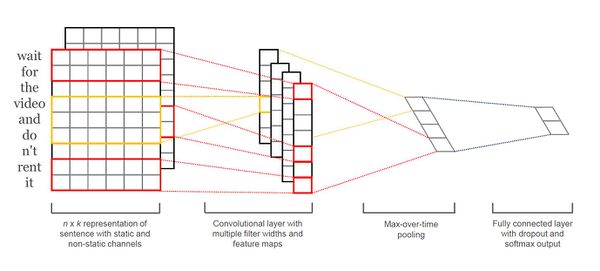

Theory of Convolutional Neural Networks

Let [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{x}_{i:i+j} }[/math] represents the concatenation of words [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{x}_i, \boldsymbol{x}_{i+1}, \dots, \boldsymbol{x}_{i+j} }[/math] with concatenation operation [math]\displaystyle{ \oplus }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{x}_{i:i+j} = \boldsymbol{x}_i \oplus \boldsymbol{x}_{i+1} \oplus \dots \oplus \boldsymbol{x}_{i+j} }[/math]. Then, a sentence of length [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] is a concatenation of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] words, denoted as [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{x}_{1:n} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{x}_{1:n} = \boldsymbol{x}_1 \oplus \boldsymbol{x}_2 \oplus \dots \oplus \boldsymbol{x}_n }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{x}_i \in \mathbb{R}^k }[/math] denote the [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]-th word in the sentence, [math]\displaystyle{ i \in \{ 1, \dots, n \} }[/math].

A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is a nonlinear function [math]\displaystyle{ f: \mathbb{R}^{hk} \to \mathbb{R} }[/math] that computes a series of outputs [math]\displaystyle{ c_i }[/math] from windows of [math]\displaystyle{ h }[/math] words [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{x}_{i:i+h-1} }[/math] in the sentence. [math]\displaystyle{ c_i = f \left( \boldsymbol{w} \cdot \boldsymbol{x}_{i:i+h-1} + b \right) }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{w} \in \mathbb{R}^{hk} }[/math] is call a filter and [math]\displaystyle{ b \in \mathbb{R} }[/math] is a bias term, [math]\displaystyle{ i \in \{ 1, \dots, n-h+1 \} }[/math]. The outputs form a [math]\displaystyle{ (n-h+1) }[/math]-dimensional vector [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{c} = \left[ c_1, c_2, \dots, c_{n-h+1} \right] }[/math], called a feature map.

To capture the most important feature from a feature map, we take the maximum value [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{c} = max \{ \boldsymbol{c} \} }[/math]. Since each filter corresponds to one feature, we obtain several features from multiple filters the model uses which form a penultimate layer. The penultimate layer then gets passed into a fully connected softmax layer which produces the probability distribution over labels.

Below is a slight variant of CNN with two "channels" of word vectors: static vectors and fine-tuned vectors via backpropagaton. We calculate [math]\displaystyle{ c_i }[/math] by applying each filter to both channels and then adding them together. The rest of the model is equivalent to a single channel CNN architecture as described above.

Model Regularization

To prevent co-adaptation and overfitting, we randomly drop out some hidden units on penultimate layer by setting them to zero during forward propagation and restrict the [math]\displaystyle{ l_2 }[/math]-norm of the weight vectors.

For example, consider a penultimate layer [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{l} }[/math] obtained from [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] filters, [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{l} = \left[ \hat{c}_1, \dots, \hat{c}_m \right] }[/math]. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{u} \in \mathbb{R}^m }[/math] be a weight vector, [math]\displaystyle{ \boldsymbol{r} \in \mathbb{R}^m }[/math] be a "dropout" vector of Bernoulli random variables with a proportion of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] being 1, and [math]\displaystyle{ \circ }[/math] be an element-wise multiplication operator. In forward propagation, instead of using [math]\displaystyle{ y = \boldsymbol{u} \cdot \boldsymbol{l} + b }[/math], we use [math]\displaystyle{ y = \boldsymbol{u} \cdot \left( \boldsymbol{l} \circ \boldsymbol{r} \right) + b }[/math] to obtain the output [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math]. Gradients are only backpropagated through "remaining" units. Then at testing, we scale the learned weight vector by [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\boldsymbol{u}} = p\boldsymbol{u} }[/math]. We use [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{\boldsymbol{u}} }[/math] to score dropout sentences. Additionally, at each gradient descent step, we restrict [math]\displaystyle{ \| \boldsymbol{u} \|_2 = s }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ \| \boldsymbol{u} \|_2 \gt s }[/math].

Datasets and Experimental Setup

There are various benchmark for classification, for example:

MR:

Movie reviews with one sentence per review.

Class: positive/negative (Pang and Lee, 2005).

SST-1:

Standford Sentiment Treebank (An extension of MR) with train/dev*/test splits.

Classes: very positive, positive, neutral, negative, very negative.

dev set *: The set used for selecting the best performing model. (re-labeled by Socher er al. 2013)

SST-2:

Same as SST-1 but with neutral reviews removed and binary labels.

Class: positive/negative

Subj:

To classify a sentence as subjective or objective.

Class: subjective/objective (Pang and Lee, 2004)

TREC:

TREC question dataset, classifying a question into 6 question types

Class: question about person, location, numeric information. etc (Li and Roth, 2002).

CR:

Customer review towards various products (i.e. cameras, MP3 etc.).

Class: positive/negative reviews. (Hu and Liiu, 2004)

MPQA:

Opinion polarity detection subtask of the MPQA dataset.

(Wiebe et al., 2005).

Hyperparameters and Training

If no dev set is specified, then randomly pick 10 percent of training set as the dev set.

Using grid search, we find out the best combination of hyperparameters. On dev set of SST-2 dev set, we set all the hyperparameters: rectified linear units, filter windows(h) of 3, 4, 5 with 100 feature maps each, dropout rate (p) of 0.5, l2 constraint (s) of 3, and mini-batch size of 50.

Training is done through stochastic gradient descent over mini-batches with the Adadelta update rule(Zeiler, 2012)

Pre-trained Word Vectors

It is a popular method to initialize word vector through an unsupervised neural language model, which improves performance in the absence of a large supervised training set (Collobert et al ., 2011; Socher et al., 2011; lyyer et al,. 2014).

We use 'word2vec' vectors that were trained on 100 billion words from Google News. The vectors have dimensionality of 300 and were trained using bag-of-words architecture*( Mikolov et al., 2013). For words not present in the set of pre-trained words, we initialized them randomly.

Model Variations

CNN-rand:

baseline model where all words are randomly initialized and then modified during training

CNN-static:

model with pre-trained vectors from 'word2vec'(publicly available).

All words are randomly initialized and are kept static and the other parameters of the model are learned

CNN-non-static:

same as above but the pre-trained vectors are fine-tuned for each task

CNN-multichannel:

A model with two sets of word vectors.

Each set is a 'channel' and each filter is applied on both channels. One channel is fine-tuned via back-propagation, and the other is static(unchanged).

Both channels are initialized from 'word2vec'.

We keep other sources of randomness uniform within each datasets(such as CV-fold assignment, initialization of unknown word vectors, initialization of CNN parameters) to eliminate the effect of the above variations versus other random factors.

Training and Results

Scoring Method

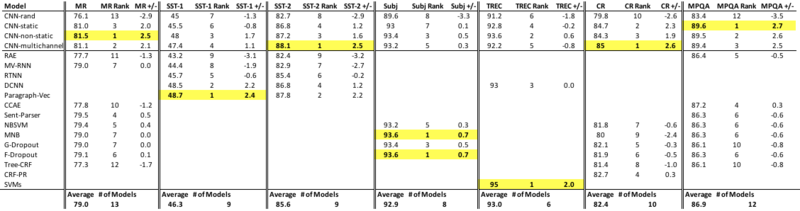

The results of the CNN models against other methods can be seen in Table A. The accuracy of the four model variations of the CNN described above are compared with the accuracy (on a scale of 0 to 100) of various other methods.

Results

The baseline model (CNN-rand) with all randomly initialized words does not perform well compared to the other models as expected. In many cases, the baseline model performs the worst or close to the worst. Much to the surprise of the authors, the model with static vectors (CNN-static) performed exceptionally well, even against more sophisticated models from other research studies which have used static representations. As we will talk about, this suggests that pre-trained vectors are a useful ‘universal’ feature, that can be used against various datasets to improve accuracy.

The Effect of the Multichannel Model

One of the primary goals of the multichannel model was to prevent the issue of overfitting, and as a consequence, provide better results than the single channel. The idea was limit the deviation of learned vectors from the original values. The results of the experiments, however, did not show any significant evidence that the multichannel model performed better than the single channel models. In fact, there were some experiments in which single channel models scored better than the multichannel model, and some where the multichannel model scored better than the single channel models.

The Effects of Static vs. Non-Static Models

One of the key differences observed between the static and non-static models is that the fine-tuning of vectors in the non-static model allowed it to make meaningful associations, based on expressions of sentiment and uses of various punctuation. On the other hand, the static channel made stronger association based on syntax. Based on the results, the non-static model generally performed better than the static channel.

Further Observations

The multiple filter widths and feature maps of the CNN results in much greater performance than other models with similar architecture. Another feature of the CNN that improved performance was dropout, on average adding between 2-4% accuracy. When initializing words not in the word2vec vectors, performance was improved by sampling each dimension from [-a,a], where a is a value chosen to ensure the randomly initialized vectors and the ore-trained vectors have the same variance.

Criticisms

The author has acknowledged that at the time of his original experiments he did not have access to a GPU and thus could not run many differing experiments. Therefore the paper is missing things like ablation studies, which refers to removing/adding some feature of the model/algorithm and seeing how that can affect performance of the CNN (e.g. dropout rate). When a model is assessed it would be vital for the author to replicate the k-fold cross validation procedure and include ranges and variances of the performance. The author only reported the mean of the CV results but this overlooks the randomness of the stochastic processes which were used. This paper did not report variances despite using stochastic gradient descent, random dropout and random weight parameter initialization, which are all highly stochastic learning procedures. For more on an exhaustive analysis of model variants on CNNs Ye Zhang and Byron C. Wallace did a sensitivity analysis of CNNs for sentence classification (https://arxiv.org/pdf/1510.03820.pdf).

How does using different word vector representations effect the results?

More Formulations/New Concepts

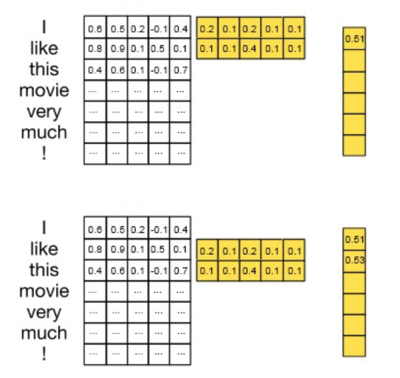

Learning to apply CNN on word embeddings, keeping track of the dimensions of the matrices can be confusing. The aim of this short post is to simply keep track of these dimensions and understand how CNN works for sentence classification. We would use a one-layer CNN on a 7-word sentence, with word embeddings of dimension 5 — a toy example to aid the understanding of CNN.

First, the two-word filter, represented by the 2 x 5 yellow matrix w, overlays across the word vectors of “I” and “like”. Next, it performs an element-wise product for all its 2 x 5 elements, and then sum them up and obtain one number (0.6 x 0.2 + 0.5 x 0.1 + … + 0.1 x 0.1 = 0.51). 0.51 is recorded as the first element of the output sequence, o, for this filter. Then, the filter moves down 1 word and overlays across the word vectors of ‘like’ and ‘this’ and perform the same operation to get 0.53. Therefore, o will have the shape of (s–h+1 x 1), in this case (7–2+1 x 1) To obtain the feature map, c, we add a bias term (a scalar, i.e., shape 1×1) and apply an activation function (e.g. ReLU). This gives us c, with the same shape as o (s–h+1 x 1).

CBOW: The input to the model could be [math]\displaystyle{ {w}_{i-2} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {w}_{i-1} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {w}_{i+1} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ {w}_{i+2} }[/math], the preceding and following words of the current word we are at. The output of the neural network will be [math]\displaystyle{ {w}_{i} }[/math]. Hence you can think of the task as "predicting the word given its context"

Note that the number of words we use depends on your setting for the window size.

Conclusion

Yoon Kim described a series of experiments with CNNs using word2vec for differing types of sentence classifications. With minimal hyperparameter tuning and a simple CNN with 1 layer of convolution the models performed in some cases better than the other established benchmarks. The author was able to beat the provided benchmarks in 4/7 datasets effectively demonstrating the power of CNNs for sentence classification.

Source

Kim, Y. (2014). Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/pdf/1408.5882.pdf. arXiv:1408.5882v2 [cs.CL].