memory Networks: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

In short, a response is produced by scoring each word in a set of candidate words against the representation produced by the combination of the input and the two supporting words. The highest scoring candidate word is then chosen as the model's output. The learned portions of <math>\ O </math> and <math>\ R </math> are the parameters of the functions <math>\ S_O </math> and <math>\ S_R </math>, which perform embeddings of the raw text constituting each function argument, and then return the dot product of these two embeddings as a score. Formally, the function <math>\ S_O </math> can be defined as follows; <math>\ S_R </math> is defined analogously: | In short, a response is produced by scoring each word in a set of candidate words against the representation produced by the combination of the input and the two supporting words. The highest scoring candidate word is then chosen as the model's output. The learned portions of <math>\ O </math> and <math>\ R </math> are the parameters of the functions <math>\ S_O </math> and <math>\ S_R </math>, which perform embeddings of the raw text constituting each function argument, and then return the dot product of these two embeddings as a score. Formally, the function <math>\ S_O </math> can be defined as follows; <math>\ S_R </math> is defined analogously: | ||

:<math>\ S_O(x, y) = \Phi_x(x)^T U^T U \Phi_y(y) </math> | :<math>\ S_O(x, y) = \Phi_x(x)^T U^T U \Phi_y(y) </math> | ||

In this equation, <math>\ U </math> is an <math>\ n x D </math> matrix, where ''n'' is the dimension of the embedding space, and ''D'' is the number of features used to represent each function argument. <math>\ \Phi_x</math> and <math>\ \Phi_y </math> are functions that map each argument (which are strings) into the feature space. In the implementations considered in this paper, the feature space makes use of a bag-of-words representation, such that there are 3 binary features for each word in the models vocabulary. The first feature corresponds to the presence of the word in the input ''x'', the second feature corresponds to the presence of the word in first supporting memory that is being used to select a second supporting memory, and the third feature representation corresponds to the presence of the word in a candidate memory being scored (i.e. either the first or second supporting memory retrieved by the model). Having these different features allows the model to learn distinct representations for the same word depending on whether the word is present in an input question or in a string stored in memory. | |||

Intuitively, it helps to think of the columns of <math>\ U </math> containing distributed representations of each word in the vocabulary (specifically, there are 3 representations and hence 3 columns devoted to each word). The binary feature representation <math>\ \Phi_x(x)</math> maps the text in ''x'' onto a binary feature vector, where 1's in the vector indicate the presence of a particular word in ''x'', and 0's indicate the absence of this word. Note that different elements of the vector will be set to 1 depending on whether the word occurs in the input ''x'' or in a supporting memory (i.e. when ''x'' is a list containing the input and a supporting memory). The matrix-vector multiplications in the above equation effectively extract and sum the distributed representations corresponding to each of the inputs, ''x'' and ''y''. Thus, a single distributed representation is produced for each input, and the resulting score is the dot product of these two vectors (which in turn is the cosine of the angle between the vectors scaled by the product of the vector norms). In the case where ''x'' is the input query, and ''y'' is a candidate memory, a high dot product indicates that the model thinks that the candidate in question is very relevant to answering the input query. In the case where ''x'' is the output of <math>\ O</math> and ''y'' is a candidate response word, a high dot product indicates that the model thinks that the response word is an appropriate answer given the output feature representation produced by <math>\ O</math>. | |||

The goal of learning is find an embedding matrix <math>\ U</math> in which the representations produced for queries, supporting memories, and responses are spatially related such that representations of relevant supporting memories are close to the representations of a query, and such that representations of individual words are close to the output feature representations of the questions they answer. The method used to perform this learning is described in the next section. | |||

= The Training Procedure = | = The Training Procedure = | ||

Revision as of 00:22, 17 November 2015

Content in progress

Introduction

Most supervised machine learning models are designed to approximate a function that maps input data to a desirable output (e.g. a class label for an image or a translation of a sentence from one language to another). In this sense, such models perform inference using a 'fixed' memory in the form of a set of parameters learned during training. For example, the memory of a recurrent neural network is constituted largely by the weights on the recurrent connections to its hidden layer (along with the layer's activities). As is well known, this form of memory is inherently limited given the fixed dimensionality of the weights in question. It is largely for this reason that recurrent nets have difficulty learning long-range dependencies in sequential data. Learning such dependencies, note, requires remembering items in a sequence for a large number of time steps.

For an interesting class of problems, it is essential for a model to be able to learn long-term dependencies, and to more generally be able to learn to perform inferences using an arbitrarily large memory. Question-answering tasks are paradigmatic of this class of problems, since performing well on such tasks requires remembering all of the information that constitutes a possible answer to the questions being posed. In principle, a recurrent network such as an LSTM could learn to perform QA tasks, but in practice, the amount of information that can be retained by the weights and the hidden states in the LSTM is simply insufficient.

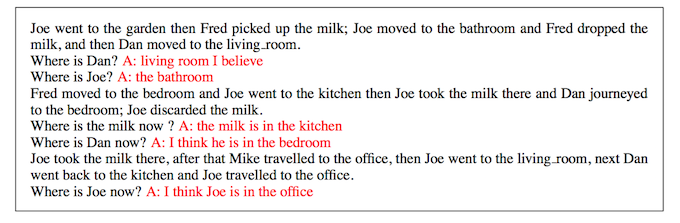

Given this need for a model architecture the combines inference and memory in a sophisticated manner, the authors of this paper propose what they refer to as a "Memory Network". In brief, a memory network is a model that learns to read and write data to an arbitrarily large long-term memory, while also using the data in this memory to perform inferences. The rest of this summary describes the components of a memory network in greater detail, along with some experiments describing its application to a question answering task involving short stories. Below is an example illustrating the model's ability to answer simple questions after being presented with short, multi-sentence stories.

Model Architecture

A memory network is composed of a memory [math]\displaystyle{ \ m }[/math] (in the form of a collection of vectors or strings, indexed individually as [math]\displaystyle{ \ m_i }[/math]), and four possibly learned functions [math]\displaystyle{ \ I }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \ G }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ \ R }[/math]. The functions are defined as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ I }[/math] maps a natural language expression onto an 'input' feature representation (e.g., a real-valued vector). The input can either be a fact to be added to the memory [math]\displaystyle{ \ m }[/math] (e.g. 'John is at the university') , or a question for which an answer is being sought (e.g. 'Where is John?').

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ G }[/math] updates the contents of the memory [math]\displaystyle{ \ m }[/math] on the basis of an input. The updating can involve simply writing the input to new memory location, or it can involve the modification or compression of existing memories to perform a kind of generalization on the state of the memory.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math] produces an 'output' feature representation given a new input and the current state of the memory. The input and output feature representations reside in the same embedding space.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ R }[/math] produces a response given an output feature representation. This response is usually a word or a sentence, but in principle it could also be an action of some kind (e.g. the movement of a robot)

To give a quick overview of how the model operates, an input x will first be mapped to a feature representation [math]\displaystyle{ \ I(x) }[/math] Then, for all memories i in m, the following update is applied: [math]\displaystyle{ \ m_i = G(m_i, I(x), m) }[/math]. This means that each memory is updated on the basis of the input x and the current state of the memory [math]\displaystyle{ \ m }[/math]. In the case where each input is simply written to memory, [math]\displaystyle{ \ G }[/math] might function to simply select an index that is currently empty and write [math]\displaystyle{ \ I(x) }[/math] to the memory location corresponding to this index. Next, an output feature representation is computed as [math]\displaystyle{ \ o=O(I(x), m) }[/math], and a response, [math]\displaystyle{ \ r }[/math], is computed directly from this feature representation as [math]\displaystyle{ \ r=R(o) }[/math]. [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math] can be interpreted as retrieving a small selection of memories that are relevant to producing a good response, and [math]\displaystyle{ \ R }[/math] actually produces the response given the feature representation produced from the relevant memories by [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math].

A Basic Implementation

In a simple version of the memory network, input text is just written to memory in unaltered form. Or in other words, [math]\displaystyle{ \ I(x) }[/math] simply returns x, and [math]\displaystyle{ \ G }[/math] writes this text to a new memory slot [math]\displaystyle{ \ m_{N+1} }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ \ N }[/math] is the number of currently filled slots. The memory is accordingly an array of strings, and the inclusion of a new string does nothing to modify existing strings.

Given as much, most of the work being done by the model is performed by the functions [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \ R }[/math]. The job of [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math] is to produce an output feature representation by selecting [math]\displaystyle{ \ k }[/math] supporting memories from [math]\displaystyle{ \ m }[/math] on the basis of the input x. In the experiments described in this paper, [math]\displaystyle{ \ k }[/math] is set to either 1 or 2. In the case that [math]\displaystyle{ \ k=1 }[/math], the function [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math] behaves as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ o_1 = O_1(x, m) = argmax_{i = 1 ... N} S_O(x, m_i) }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \ S_O }[/math] is a function that scores a candidate memory for its compatibility with x. Essentially, one 'supporting' memory is selected from [math]\displaystyle{ \ m }[/math] as being most likely to contain the information needed to answer the question posed in [math]\displaystyle{ \ x }[/math]. In this case, the output is [math]\displaystyle{ \ o_1 = [x, m_{o_1}] }[/math], or a list containing the input question and one supporting memory. Alternatively, in the case that [math]\displaystyle{ \ k=2 }[/math]', a second supporting memory is selected on the basis of the input and the first supporting memory as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ o_2 = O_2(x, m) = argmax_{i = 1 ... N} S_O([x, m_{o_1}], m_i) }[/math]

Now, the overall output is [math]\displaystyle{ \ o_2 = [x, m_{o_1}, m_{o_2}] }[/math]. (These lists are translated into feature representations as described below). Finally, the result of [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math] is used to produce a response in the form of a single word via [math]\displaystyle{ \ R }[/math] as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ r = argmax_{w \epsilon W} S_R([x, m_{o_1}, m_{o_2}], w) }[/math]

In short, a response is produced by scoring each word in a set of candidate words against the representation produced by the combination of the input and the two supporting words. The highest scoring candidate word is then chosen as the model's output. The learned portions of [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \ R }[/math] are the parameters of the functions [math]\displaystyle{ \ S_O }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \ S_R }[/math], which perform embeddings of the raw text constituting each function argument, and then return the dot product of these two embeddings as a score. Formally, the function [math]\displaystyle{ \ S_O }[/math] can be defined as follows; [math]\displaystyle{ \ S_R }[/math] is defined analogously:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \ S_O(x, y) = \Phi_x(x)^T U^T U \Phi_y(y) }[/math]

In this equation, [math]\displaystyle{ \ U }[/math] is an [math]\displaystyle{ \ n x D }[/math] matrix, where n is the dimension of the embedding space, and D is the number of features used to represent each function argument. [math]\displaystyle{ \ \Phi_x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \ \Phi_y }[/math] are functions that map each argument (which are strings) into the feature space. In the implementations considered in this paper, the feature space makes use of a bag-of-words representation, such that there are 3 binary features for each word in the models vocabulary. The first feature corresponds to the presence of the word in the input x, the second feature corresponds to the presence of the word in first supporting memory that is being used to select a second supporting memory, and the third feature representation corresponds to the presence of the word in a candidate memory being scored (i.e. either the first or second supporting memory retrieved by the model). Having these different features allows the model to learn distinct representations for the same word depending on whether the word is present in an input question or in a string stored in memory.

Intuitively, it helps to think of the columns of [math]\displaystyle{ \ U }[/math] containing distributed representations of each word in the vocabulary (specifically, there are 3 representations and hence 3 columns devoted to each word). The binary feature representation [math]\displaystyle{ \ \Phi_x(x) }[/math] maps the text in x onto a binary feature vector, where 1's in the vector indicate the presence of a particular word in x, and 0's indicate the absence of this word. Note that different elements of the vector will be set to 1 depending on whether the word occurs in the input x or in a supporting memory (i.e. when x is a list containing the input and a supporting memory). The matrix-vector multiplications in the above equation effectively extract and sum the distributed representations corresponding to each of the inputs, x and y. Thus, a single distributed representation is produced for each input, and the resulting score is the dot product of these two vectors (which in turn is the cosine of the angle between the vectors scaled by the product of the vector norms). In the case where x is the input query, and y is a candidate memory, a high dot product indicates that the model thinks that the candidate in question is very relevant to answering the input query. In the case where x is the output of [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math] and y is a candidate response word, a high dot product indicates that the model thinks that the response word is an appropriate answer given the output feature representation produced by [math]\displaystyle{ \ O }[/math].

The goal of learning is find an embedding matrix [math]\displaystyle{ \ U }[/math] in which the representations produced for queries, supporting memories, and responses are spatially related such that representations of relevant supporting memories are close to the representations of a query, and such that representations of individual words are close to the output feature representations of the questions they answer. The method used to perform this learning is described in the next section.