stat341f11: Difference between revisions

| Line 168: | Line 168: | ||

Although this method is useful, it isn't practical in many cases since we can't always obtain <math>F</math> or <math> F^{-1} </math> as some functions are not integrable or invertible. | Although this method is useful, it isn't practical in many cases since we can't always obtain <math>F</math> or <math> F^{-1} </math> as some functions are not integrable or invertible. Let's look at some examples: | ||

*Continuous case | |||

If we want to use this method to draw the ''pdf'' of '''normal distribution''', we may find ourselves get stuck in finding its ''cdf''. | |||

The simplest case of '''normal distribution''' is <math>f(x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}}</math>. | |||

And it is known to everyone that the ''cdf'' is <math>F(x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\int_{-\infty}^{x}{e^{-\frac{u^2}{2}}}du</math>. Actually it is hard to find the <math>\int_{-\infty}^{x}{e^{-\frac{u^2}{2}}}du</math>. So the '''cdf''' cannot take a specific form, not to mention its inverse function. | |||

*Discrete case | |||

It is easy for us to simulate when there are only a few values taken by the particular random variable, like the case above. | |||

And it is easy to simulate the '''binomial distribution''' <math>X \sim~ \mathrm{B}(n,p)</math> when the parameter n is not too large. | |||

But when n increases in a great amount, say 50, it is hard to do so. | |||

===Acceptance/Rejection Sampling=== | ===Acceptance/Rejection Sampling=== | ||

Revision as of 04:18, 25 September 2011

Editor Sign Up

Sampling - Sept 20, 2011

The meaning of sampling is to generate data points or numbers such that these data follow a certain distribution.

i.e. From [math]\displaystyle{ x \sim~ f(x) }[/math] sample [math]\displaystyle{ \,x_{1}, x_{2}, ..., x_{1000} }[/math]

In practice, it maybe difficult to find the joint distribution of random variables. Through simulating the random variables, we can inference from the data.

Sample from uniform distribution.

Computers can't generate random numbers as they are deterministic but they can produce pseudo random numbers.

Multiplicative Congruential

- involves three parameters: integers [math]\displaystyle{ \,a, b, m }[/math], and an initial value [math]\displaystyle{ \,x_0 }[/math] we call the seed

- a sequence of integers is defined as

- [math]\displaystyle{ x_{k+1} \equiv (ax_{k} + b) \mod{m} }[/math]

Example: [math]\displaystyle{ \,a=13, b=0, m=31, x_0=1 }[/math] creates a uniform histogram.

MATLAB code for generating 1000 random numbers using the multiplicative congruential method:

a=13;

b=0;

m=31;

x(1)=1;

for ii = 1:1000

x(ii+1) = mod(a*x(ii)+b,m);

end

MATLAB code for displaying the values of x generated:

x

MATLAB code for plotting the histogram of x:

hist(x)

Facts about this algorithm:

- In this example, the first 30 terms in the sequence are a permutation of integers from 1 to 30 and then the sequence repeats itself.

- Values are between 0 and [math]\displaystyle{ m-1 }[/math], inclusive.

- Dividing the numbers by [math]\displaystyle{ m-1 }[/math] yields numbers in the interval [math]\displaystyle{ [0,1] }[/math].

- MATLAB's

randfunction once used this algorithm with [math]\displaystyle{ a=7^5, b=0, m=2^{31}-1 }[/math], for reasons described in Park and Miller's 1988 paper "Random Number Generators: Good Ones are Hard to Find" (available online).

Inverse Transform Method

- We want to sample from distribution [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] with probability density function (pdf) [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math]

- Assume that the cumulative distribution function (cdf) [math]\displaystyle{ F(x) }[/math] and its inverse [math]\displaystyle{ F^{-1}(x) }[/math] can be found.

- [math]\displaystyle{ P(a\lt x\lt b)=\int_a^{b} f(x) dx }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ cdf=F(x)=P(X\lt =x)=\int_{-\infty}^{x} f(x) dx }[/math]

Theorem:

Take [math]\displaystyle{ U \sim~ \mathrm{Unif}[0, 1] }[/math] and let [math]\displaystyle{ x=F^{-1}(u) }[/math]. Then x has distribution function [math]\displaystyle{ F(\cdot) }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ F(x)=P(X\lt =x) }[/math].

Let [math]\displaystyle{ F^{-1}() }[/math] denote the inverse of [math]\displaystyle{ F() }[/math]. Therefore [math]\displaystyle{ F(x)=u \implies x=F^{-1}(u) }[/math]

Take the exponential distribution for example

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,f(x)={\lambda}e^{-{\lambda}x} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,F(x)=\int_0^x {\lambda}e^{-{\lambda}u} du }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,F(x)=1-e^{-{\lambda}x} }[/math]

Let: [math]\displaystyle{ \,F(x)=y }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,y=1-e^{-{\lambda}x} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,ln(1-y)={-{\lambda}x} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,x=\frac{ln(1-y)}{-\lambda} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,F^{-1}(x)=\frac{-ln(1-x)}{\lambda} }[/math]

Therefore, to get a exponential distribution from a uniform distribution takes 2 steps.

- Step 1. Draw [math]\displaystyle{ U \sim~ \mathrm{Unif}[0, 1] }[/math]

- Step 2. [math]\displaystyle{ x=\frac{-ln(1-U)}{\lambda} }[/math]

MATLAB code for exponential distribution case,assuming [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda=0.5 }[/math]

for ii = 1:1000

u = rand;

x(ii)=-log(1-u)/0.5;

ii+1;

end

hist(x)

Now we just have to show the generated points have a cdf of [math]\displaystyle{ F(x) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,p(F^{-1}(u)\lt =x) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,p(F(F^{-1}(u))\lt =F(x)) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,p(u\lt =F(x)) }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \,=F(x) }[/math]

QED

Discrete Case

This same technique can be applied to the discrete case. Generate a discrete random variable [math]\displaystyle{ \,x }[/math] that has probability mass function [math]\displaystyle{ \,P(X=x_i)=P_i }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \,x_0\lt x_1\lt x_2... }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \,\sum_i P_i=1 }[/math]

- Step 1. Draw [math]\displaystyle{ u \sim~ \mathrm{Unif}[0, 1] }[/math]

- Step 2. [math]\displaystyle{ \,x=x_i }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ \,F(x_{i-1})\lt u\lt =F(x_i) }[/math]

Inverse Transform Method and Acceptance/Rejection Method - Sept 22, 2011

Discrete Case (continued)

Let x be a discrete random variable with the following probability mass function:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} P(X=0) = 0.3 \\ P(X=1) = 0.2 \\ P(X=2) = 0.5 \end{align} }[/math]

Given the pmf, we now need to find the cdf.

We have:

- [math]\displaystyle{ F(x) = \begin{cases} 0 & x \lt 0 \\ 0.3 & x \lt 1 \\ 0.5 & x \lt 2 \\ 1 & x \lt 3 \end{cases} }[/math]

We can apply the inverse transform method to obtain our random numbers from this distribution.

Pseudo Code for generating the random numbers:

Draw U ~ Unif[0,1]

if U < 0.3

x = 0

else if

0.3 <= U < 0.5

x = 1

else

0.5 <= U < 1

x = 2

MATLAB code for generating 1000 random numbers in the discrete case:

for ii = 1:1000

u = rand;

if u < 0.3

x(ii) = 0;

else if u < 0.5

x(ii) = 1;

else

x(ii) = 2;

end

end

Pseudo code for the Discrete Case:

1. Draw U ~ Unif [0,1]

2. If [math]\displaystyle{ U \leq P_0 }[/math], deliver [math]\displaystyle{ X = x_0 }[/math]

3. Else if [math]\displaystyle{ U \leq P_0 + P_1 }[/math], deliver [math]\displaystyle{ X = x_1 }[/math]

4. Else If [math]\displaystyle{ U \leq P_0 +....+ P_k }[/math], deliver [math]\displaystyle{ X = x_k }[/math]

Although this method is useful, it isn't practical in many cases since we can't always obtain [math]\displaystyle{ F }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ F^{-1} }[/math] as some functions are not integrable or invertible. Let's look at some examples:

- Continuous case

If we want to use this method to draw the pdf of normal distribution, we may find ourselves get stuck in finding its cdf. The simplest case of normal distribution is [math]\displaystyle{ f(x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}} }[/math]. And it is known to everyone that the cdf is [math]\displaystyle{ F(x)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}}\int_{-\infty}^{x}{e^{-\frac{u^2}{2}}}du }[/math]. Actually it is hard to find the [math]\displaystyle{ \int_{-\infty}^{x}{e^{-\frac{u^2}{2}}}du }[/math]. So the cdf cannot take a specific form, not to mention its inverse function.

- Discrete case

It is easy for us to simulate when there are only a few values taken by the particular random variable, like the case above. And it is easy to simulate the binomial distribution [math]\displaystyle{ X \sim~ \mathrm{B}(n,p) }[/math] when the parameter n is not too large. But when n increases in a great amount, say 50, it is hard to do so.

Acceptance/Rejection Sampling

Sampling from [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math] can be difficult. Another general method for generating random numbers is acceptance/rejection sampling. Here, [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math] is approximated by another function, say [math]\displaystyle{ g(x) }[/math], which is easier to calculate.

Suppose we assume the following:

1. There exists another distribution [math]\displaystyle{ g(x) }[/math] that is easier to work with and that you know how to sample from, and

2. There exists a constant c such that [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) \leq c \cdot g(x) }[/math] for all x

Under these assumptions, we can sample from [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math] by sampling from [math]\displaystyle{ g(x) }[/math]

General Idea

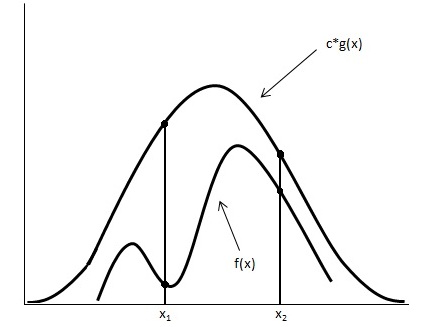

Looking at the image below we have graphed [math]\displaystyle{ c \cdot g(x) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math].

Using the acceptance/rejection method we will accept some of the points from [math]\displaystyle{ g(x) }[/math] and reject some of the points from [math]\displaystyle{ g(x) }[/math]. The points that will be accepted from [math]\displaystyle{ g(x) }[/math] will have a distribution similar to [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math]. We can see from the image that the values around [math]\displaystyle{ x_1 }[/math] will be sampled more often under [math]\displaystyle{ c \cdot g(x) }[/math] than under [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) }[/math], so we will have to reject more samples taken at x1. Around [math]\displaystyle{ x_2 }[/math] the number of samples that are drawn and the number of samples we need are much closer, so we accept more samples that we get at [math]\displaystyle{ x_2 }[/math]

Procedure

1. Draw y ~ g

2. Draw U ~ Unif [0,1]

3. If [math]\displaystyle{ U \leq \frac{f(y)}{c \cdot g(y)} }[/math] then x=y; else return to 1

Example

Sample from Beta(2,1)

In general:

Beta([math]\displaystyle{ \alpha, \beta) = \frac{\Gamma (\alpha + \beta)}{\Gamma(\alpha)\Gamma(\beta)} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ x^{\alpha-1} }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ (1-x)^{\beta-1} }[/math]

Note: [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma(n) = (n-1)! }[/math] if n is a positive integer

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} f(x) &= Beta(2,1) \\ &= \frac{\Gamma(3)}{\Gamma(2)\Gamma(1)} x^1(1-x)^0 \\ &= \frac{2!}{1! 0!}\cdot (1) x \\ &= 2x \end{align} }[/math]

We want to choose [math]\displaystyle{ g(x) }[/math] that is easy to sample from. So we choose [math]\displaystyle{ g(x) }[/math] to be uniform distribution.

We now want a constant c such that [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) \leq c \cdot g(x) }[/math]

So,

[math]\displaystyle{ c \geq \frac{f(x)}{g(x)} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align}c &= max \frac {f(x)}{g(x)} \\

&= max \frac {2x}{1} \\

&= 2 \end{align} }[/math]

Now that we have c,

1. Draw y ~ g(x) => Draw y ~ Unif [0.1]

2. Select U ~ Unif [0,1]

3. if [math]\displaystyle{ u \leq \frac{2y}{2 \cdot 1} }[/math] then x=y; else return to 1

Matlab code for generating 1000 random numbers:

while ii < 1000

y = rand;

u = rand;

if u <= y

x(ii)=y;

ii=ii+1;

end

end

hist(x)

Limitations

Most of the time we have to sample many more points from g(x) before we can obtain an acceptable amount of samples from f(x), hence this method may not be computationally efficient. It depends on our choice of g(x). For example, in the example above to sample from Beta(2,1), we need roughly 2000 samples from g(X) to get 1000 acceptable samples of f(x).

Proof

Mathematically, we need to show that the sample points given that they are accepted have a distribution of f(x).

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} P(y_i|accept) &= \frac{P(y_i, accept)}{P(accept)} \\ &= \frac{P(accept|y_i) P(y_i)}{P(accept)}\end{align} }[/math] (Bayes' Rule)

[math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} P(y_i) &= g(y) \\ P(accept|y_i) &= \frac{f(y)}{c \cdot g(y)} \\ P(accept) &= \int^{}_y P(x|y)P(y) dy \end{align} }[/math]

So,

[math]\displaystyle{ P(y_i|accept) = \frac{ \frac {f(y)}{c \cdot g(y)} \cdot g(y)}{\int^{}_y P(x|y)P(y) dy} }[/math]