Understanding Image Motion with Group Representations: Difference between revisions

| (17 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Introduction == | == Introduction == | ||

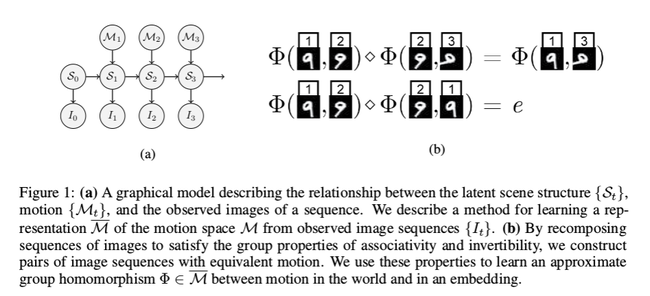

Motion perception is a key component of computer vision. It is critical to problems such as optical flow and visual odometry, where a sequence of images are used to calculate either the pixel level (local) motion or the motion of the entire scene (global). The smooth image transformation caused by camera motion is a subspace of all position image transformations. Here, we are interested in realistic | Motion perception is a key component of computer vision. It is critical to problems such as optical flow and visual odometry, where a sequence of images are used to calculate either the pixel level (local) motion or the motion of the entire scene (global). The smooth image transformation caused by camera motion is a subspace of all position image transformations. Here, we are interested in realistic transformations caused by motion, therefore unrealistic motion caused by say, face swapping, is not considered. | ||

Supervised | To be useful for understanding and acting on scene motion, a representation should capture the motion of the observer and all relevant scene content. Supervised training of such a representation is challenging: explicit motion labels are difficult to obtain, especially for nonrigid scenes where it can be unclear how the structure and motion of the scene should be decomposed. The proposed learning method does not need labeled data. Instead, the method applies constraints to learning by using the properties of motion space. The paper presents a general model of visual motion, and how the motion space properties of associativity and invertibility can be used to constrain the learning of a deep neural network. The results show evidence that the learned model captures motion in both 2D and 3D settings. This method can be used to extract useful information for vehicle localization, tracking, and odometry. | ||

[[File:paper13_fig1.png|650px|center|]] | [[File:paper13_fig1.png|650px|center|]] | ||

== Related Work == | == Related Work == | ||

The most common global representations of motion are from structure from motion (SfM) and simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), which represent poses in special Euclidean group <math> SE(3) </math> to represent a sequence of motions. However, these cannot be used to represent non-rigid or independent motions. | The most common global representations of motion are from structure from motion (SfM) and simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), which represent poses in special Euclidean group <math> SE(3) </math> to represent a sequence of motions. However, these cannot be used to represent non-rigid or independent motions. The most used method for local representation is optical flow, which estimates motion by pixel over 2-D image. Furthermore, scene flow is a more generalized method of optical flow which estimates the point trajectories from 3-D motions. The limitation of optical flow is that it only captures motion locally, which makes capturing the overall motion impossible. | ||

There are also works using CNN’s to learn optical flow using brightness constancy assumptions, and/or photometric local constraints. Works on stereo depth estimation using learning has also shown results. Regarding image sequences, there are works on shuffling the order of images to learn representations of its contents, as well as learning representations equivariant to the egomotion of the camera. | Another approach to representing motion is spatiotemporal features (STFs), which are flexible enough to represent non-rigid motions since there is usually a dimensionality reduction process involved. However these approaches are restricted to fixed windows of representation. | ||

There are also works using CNN’s to learn optical flow using brightness constancy assumptions, and/or photometric local constraints. Works on stereo depth estimation using learning has also shown results. Regarding image sequences, there are works on shuffling the order of images to learn representations of its contents, as well as learning representations equivariant to the egomotion of the camera. | |||

By learning learning representations using visual structure, recent works have used knowledge of the geometric or spatial structure of images or scenes | |||

to train representations. For example, one can trains a CNN to classify the correct configuration of image patches to learn the relationship between an image’s patches and its semantic content. The resulting representation can be fine-tuned for image classification. There are also other works that learn from sequences typically focus on static image content rather than motion | |||

== Approach == | == Approach == | ||

| Line 17: | Line 22: | ||

=== Learning Motion by Group Properties === | === Learning Motion by Group Properties === | ||

The goal is to learn a function <math> \Phi : I \times I \rightarrow \overline{M} </math>, <math> \overline{M} </math> indicating | The goal is to learn a function <math> \Phi : I \times I \rightarrow \overline{M} </math>, <math> \overline{M} </math> indicating mapping of image pairs from <math> M </math> to its representation, as well as the composition operator <math> \diamond : \overline{M} \rightarrow \overline{M} </math> that emulates the composition of these elements in <math> M </math>. For all sequences, it is assumed that for all times <math> t_0 < t_1 < t_2 ... </math>, the sequence representation should have the following properties: | ||

# Associativity: <math> \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{ | # Associativity: <math> \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_2}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_2}, I_{t_3}) = (\Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_2})) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_2}, I_{t_3}) = \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond (\Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_2}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_2}, I_{t_3})) = \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_3})</math>, which means that the motion of differently composed subsequences of a sequence are equivalent | ||

# Has Identity: <math> \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond e = \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) = e \diamond \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) </math> and <math> e=\Phi(I_{t}, I_{t}) \forall t </math>, where <math>e</math> is the null image motion and the unique identity in the latent space | # Has Identity: <math> \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond e = \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) = e \diamond \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) </math> and <math> e=\Phi(I_{t}, I_{t}) \forall t </math>, where <math>e</math> is the null image motion and the unique identity in the latent space | ||

# Invertibility: <math> \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_0}) = e </math>, so the inverse of the motion of an image sequence is the motion of that image sequence reversed | # Invertibility: <math> \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_0}) = e </math>, so the inverse of the motion of an image sequence is the motion of that image sequence reversed | ||

Also note that a notion of transitivity is assumed, specifically <math>\Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_2}) = \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_2})</math>. | |||

An embedding loss is used to approximately enforce associativity and invertibility among subsequences sampled from image sequence. Associativity is encouraged by pushing sequences with the same final motion but different transitions to the same representation. Invertibility is encouraged by pushing sequences corresponding to the same motion with but in opposite directions away from each other, as well as pushing all loops to the same representation. Uniqueness of the identity is encouraged by pushing loops away from non-identity representations. Loops from different sequences are also pushed to the same representation (the identity). | An embedding loss is used to approximately enforce associativity and invertibility among subsequences sampled from image sequence. Associativity is encouraged by pushing sequences with the same final motion but different transitions to the same representation. Invertibility is encouraged by pushing sequences corresponding to the same motion with but in opposite directions away from each other, as well as pushing all loops to the same representation. Uniqueness of the identity is encouraged by pushing loops away from non-identity representations. Loops from different sequences are also pushed to the same representation (the identity). | ||

| Line 28: | Line 36: | ||

=== Sequence Learning with Neural Networks === | === Sequence Learning with Neural Networks === | ||

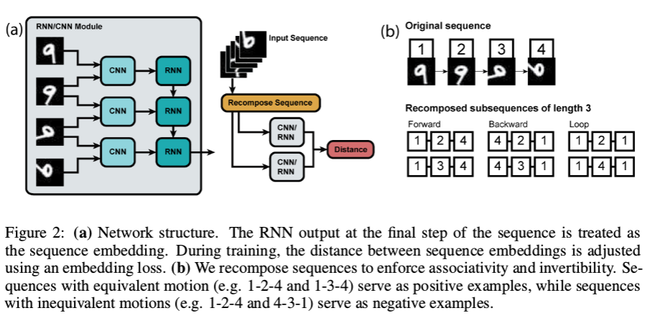

The functions <math> \Phi </math> and <math> \diamond </math> are approximated by CNN and RNN, respectively. LSTM is used for RNN. The input to the network is a sequence of images <math> I_t = \{I_1,...,I_t\} </math>. The CNN processes pairs of images | The functions <math> \Phi </math> and <math> \diamond </math> are approximated by CNN and RNN, respectively. LSTM is used for RNN. The input to the network is a sequence of images <math> I_t = \{I_1,...,I_t\} </math>. The CNN processes pairs of images and generates intermediate representations, and the LSTM operates over the sequence of CNN outputs to produce an embedding sequence <math> R_t = \{R_{1,2},...,R_{t-1,t}\} </math>. Only the embedding at the final time step is used for loss. The network is trained to minimize a hinge loss with respect to embeddings to pairs of sequences as defined below: | ||

<center><math>L(R^1,R^2) = \begin{cases} d(R^1,R^2), & \text{if positive pair} \\ max(0, m - d(R^1,R^2)), & \text{if negative pair} \end{cases}</math></center> | <center><math>L(R^1,R^2) = \begin{cases} d(R^1,R^2), & \text{if positive pair} \\ max(0, m - d(R^1,R^2)), & \text{if negative pair} \end{cases}</math></center> | ||

<center><math> d_{cosine}(R^1,R^2)=1-\frac{\langle R^1,R^2 \rangle}{\lVert R^1 \rVert \lVert R^2 \rVert} </math></center> | <center><math> d_{cosine}(R^1,R^2)=1-\frac{\langle R^1,R^2 \rangle}{\lVert R^1 \rVert \lVert R^2 \rVert} </math></center> | ||

where <math>d(R^1,R^2)</math> measure the distance between the embeddings of two sequences used for training selected to be cosine distance, <math> m </math> is a fixed margin selected to be 0.5. Positive pairs are training examples where two sequences have the same final motion, negative pairs are training examples where two sequences have the exact opposite final motion. Using L2 distances yields similar results as cosine distances. | where <math>d(R^1,R^2)</math> measure the distance between the embeddings of two sequences used for training selected to be cosine distance, <math> m </math> is a fixed scalar margin selected to be 0.5. Positive pairs are training examples where two sequences have the same final motion, negative pairs are training examples where two sequences have the exact opposite final motion. Using L2 distances yields similar results as cosine distances. | ||

Each training sequence is recomposed into 6 subsequences: two forward, two backward, and two identity. To prevent the network from only looking at static differences, subsequence pairs are sampled such that they have the same start and end frames but different motions in between. Sequences of varying lengths are also used to generalize motion on different temporal scales. Training the network with only one input images per time step was also tried, but consistently yielded work results than image pairs. | Each training sequence is recomposed into 6 subsequences: two forward, two backward, and two identity. To prevent the network from only looking at static differences, subsequence pairs are sampled such that they have the same start and end frames but different motions in between. Sequences of varying lengths are also used to generalize motion on different temporal scales. Training the network with only one input images per time step was also tried, but consistently yielded work results than image pairs. | ||

| Line 52: | Line 60: | ||

* Two LSTM cell per layer 256 hidden units each | * Two LSTM cell per layer 256 hidden units each | ||

* Sequence length of 3-5 images | * Sequence length of 3-5 images | ||

* MINIST networks with up to 12 images | |||

=== Rigid Motion in 2D === | === Rigid Motion in 2D === | ||

| Line 64: | Line 73: | ||

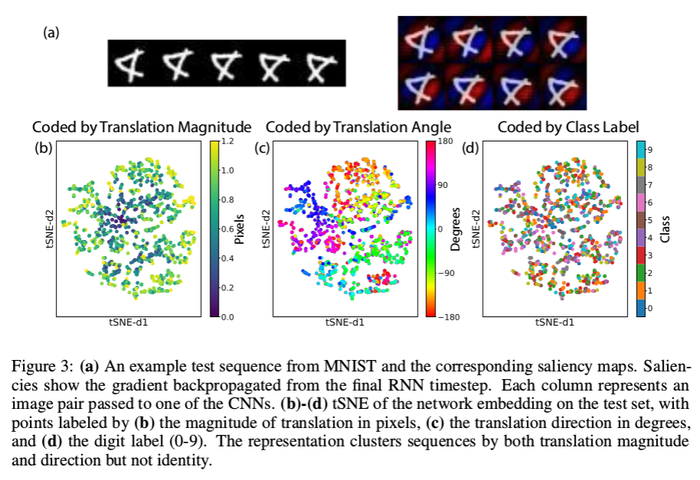

** The area that has the highest gradient means that part contributes the most to the output | ** The area that has the highest gradient means that part contributes the most to the output | ||

** The resulting salient map strongly resembles spatiotemporal energy filters of classical motion processing | ** The resulting salient map strongly resembles spatiotemporal energy filters of classical motion processing | ||

** Suggests the network is | ** Suggests the network is learning the right motion structure | ||

[[File:paper13_fig3.png|700px|center|]] | [[File:paper13_fig3.png|700px|center|]] | ||

| Line 73: | Line 82: | ||

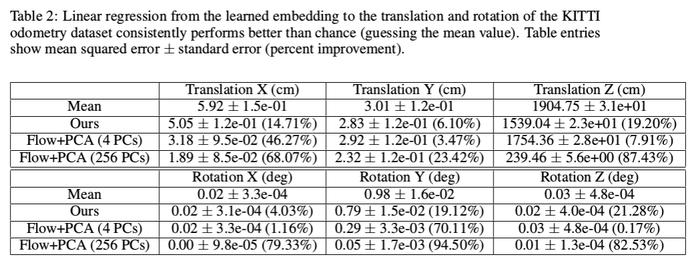

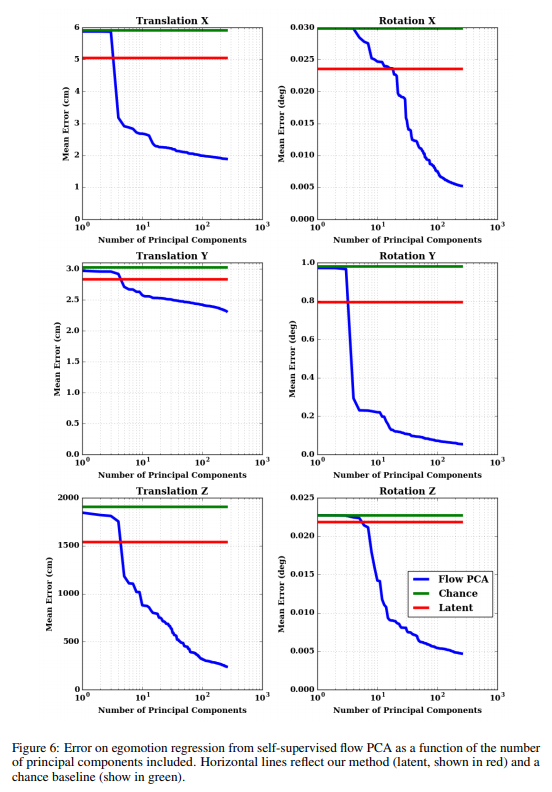

** The result is compared against self supervised flow algorithm Yu et al.(2016) after the output from the flow algorithm is downsampled, then feed through PCA, then regressed against the camera motion | ** The result is compared against self supervised flow algorithm Yu et al.(2016) after the output from the flow algorithm is downsampled, then feed through PCA, then regressed against the camera motion | ||

** The data shows it performs not as well as the supervised algorithm, but consistently better than chance (guessing the mean value) | ** The data shows it performs not as well as the supervised algorithm, but consistently better than chance (guessing the mean value) | ||

** Largest improvements are shown in X and Z translation, which also have the most variance in the data | |||

** Shows the method is able to capture dominant motion structure | ** Shows the method is able to capture dominant motion structure | ||

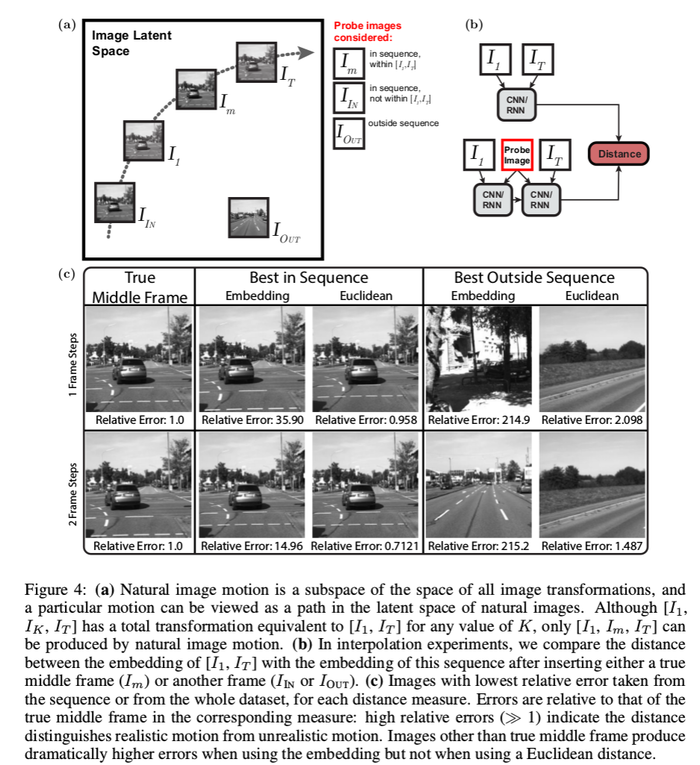

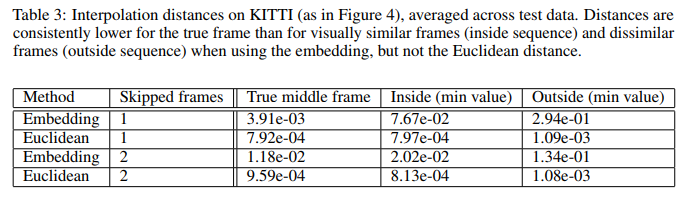

* Test performance on interpolation task | * Test performance on interpolation task | ||

| Line 96: | Line 106: | ||

== Conclusion == | == Conclusion == | ||

The | The authors presented a new model of motion and a method for learning motion representations. It is shown that by enforcing group properties we can learn motion representations that are able to generalize between scenes with disparate content. The results can be useful for navigation, prediction, and other behavioral tasks relying on motion. Due to the fact that this method does not require labelled data, it can be applied to a large variety of tasks. | ||

== Criticism == | == Criticism == | ||

Although this method does not require any labelled data, it is still learning by supervision through defined constraints. The idea of training using unlabelled data is interesting and it does have meaningful practical application. Unfortunately, the author did not provide convincing experimental results. Results from motion estimation problems are typically compared against ground truth data for their accuracy. The author performed experiments on transformed MNIST data and KITTI data. The MNIST data is transformed by the author, thus the ground truth is readily available. However the author only claimed the validity of the results through indirect means of using t-SNE and saliency map visualization. For the KITTI dataset, the author regressed the representations against ground truth for some mapping from the network output to some physical motion representation. Again, the results were compared only indirectly against ground truth. Such experimentation made the method hardly convincing and applicable to real world applications. In addition, the network does not output motion representations with physical meanings, | Although this method does not require any labelled data, it is still learning by supervision through defined constraints. The idea of training using unlabelled data is interesting and it does have meaningful practical application. Unfortunately, the author did not provide convincing experimental results. Results from motion estimation problems are typically compared against ground truth data for their accuracy. The author performed experiments on transformed MNIST data and KITTI data. The MNIST data is transformed by the author, thus the ground truth is readily available. However the author only claimed the validity of the results through indirect means of using t-SNE and saliency map visualization. For the KITTI dataset, the author regressed the representations against ground truth for some mapping from the network output to some physical motion representation. Again, the results were compared only indirectly against ground truth, also shows poor results when compared with the Flow+PCA baseline, especially for X and Z translations as well as Y rotation, which are the main elements of motion present in the KITTI dataset. Such experimentation made the method hardly convincing and applicable to real-world applications. In addition, the network does not output motion representations with physical meanings, making the proposed method useless for any real world applications. | ||

One of the motivations the authors use for this approach is that traditional SLAM formulations represent motion as a sequence of poses in <math> SE(3) </math>, and that they are unable to represent non-rigid or independent motions. There exist SLAM formulations that represent motion as [http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7353368/ Gaussian processes], as well as [http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0278364915585860 temporal basis functions], and it is quite [https://openslam.org/robotvision.html common] for inertial, monocular-camera SLAM problems to use a motion representation on <math> SIM(3) </math>, which is the group containing all scale-preserving transformations. A <math> SIM(3) </math> transformation is not, in general, rigid, so it is not true to say that modern SLAM is unable to represent non-rigid motions. Additionally, the saliency images from the KITTI experiment displaying network gradients on independently moving objects in the scene does not necessarily mean that the motion representation is capturing independent motion, it just means that the network representation is dependent on those pixels. As the authors did not provide an error comparison between images containing independent motions and those without, it is possible that these network gradients only contribute to error (in terms of the camera pose) instead of capturing independent motions. | |||

Another criticism is that the group-properties constraint the authors impose is too weak. Any set consisting of functions, their inverses, and the identity forms a group. While physical motions are one example of such a group, there are many valid groups that do not represent any coherent physical motions. That is, it's unclear whether group representations adequately describe the underlying mechanisms of the paper. | |||

Since the network has to learn both the group elements, <math>\overline{M}</math>, and the composition function, <math>\diamond</math>, associated with the group it is difficult to tell how each of them are performing. It would not be possible to perform a layer-by-layer ablation study to determine the individual contributions of the functions associated with each group. | |||

Finally, the method requires domain knowledge of the motion space and feature engineering for encoding it, which reduces the ease with which the method can be generalized to various tasks. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

Jaegle, A. (2018). Understanding image motion with group representations . ICLR. Retrieved from https://openreview.net/pdf?id=SJLlmG-AZ. | Jaegle, A. (2018). Understanding image motion with group representations . ICLR. Retrieved from https://openreview.net/pdf?id=SJLlmG-AZ. | ||

Latest revision as of 16:09, 20 April 2018

Introduction

Motion perception is a key component of computer vision. It is critical to problems such as optical flow and visual odometry, where a sequence of images are used to calculate either the pixel level (local) motion or the motion of the entire scene (global). The smooth image transformation caused by camera motion is a subspace of all position image transformations. Here, we are interested in realistic transformations caused by motion, therefore unrealistic motion caused by say, face swapping, is not considered.

To be useful for understanding and acting on scene motion, a representation should capture the motion of the observer and all relevant scene content. Supervised training of such a representation is challenging: explicit motion labels are difficult to obtain, especially for nonrigid scenes where it can be unclear how the structure and motion of the scene should be decomposed. The proposed learning method does not need labeled data. Instead, the method applies constraints to learning by using the properties of motion space. The paper presents a general model of visual motion, and how the motion space properties of associativity and invertibility can be used to constrain the learning of a deep neural network. The results show evidence that the learned model captures motion in both 2D and 3D settings. This method can be used to extract useful information for vehicle localization, tracking, and odometry.

Related Work

The most common global representations of motion are from structure from motion (SfM) and simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), which represent poses in special Euclidean group [math]\displaystyle{ SE(3) }[/math] to represent a sequence of motions. However, these cannot be used to represent non-rigid or independent motions. The most used method for local representation is optical flow, which estimates motion by pixel over 2-D image. Furthermore, scene flow is a more generalized method of optical flow which estimates the point trajectories from 3-D motions. The limitation of optical flow is that it only captures motion locally, which makes capturing the overall motion impossible.

Another approach to representing motion is spatiotemporal features (STFs), which are flexible enough to represent non-rigid motions since there is usually a dimensionality reduction process involved. However these approaches are restricted to fixed windows of representation.

There are also works using CNN’s to learn optical flow using brightness constancy assumptions, and/or photometric local constraints. Works on stereo depth estimation using learning has also shown results. Regarding image sequences, there are works on shuffling the order of images to learn representations of its contents, as well as learning representations equivariant to the egomotion of the camera.

By learning learning representations using visual structure, recent works have used knowledge of the geometric or spatial structure of images or scenes to train representations. For example, one can trains a CNN to classify the correct configuration of image patches to learn the relationship between an image’s patches and its semantic content. The resulting representation can be fine-tuned for image classification. There are also other works that learn from sequences typically focus on static image content rather than motion

Approach

The proposed method is based on the observation that 3D motions, equipped with composition, form a group. By learning the underlying mapping that captures the motion transformations, we are approximating latent motion of the scene. The method is designed to capture group associativity and invertibility.

Consider a latent structure space [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math], element of the structure space generates images via projection [math]\displaystyle{ \pi:S\rightarrow I }[/math], latent motion space [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] which is some closed subgroup of the set of homeomorphism on [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math]. For [math]\displaystyle{ s \in S }[/math], a continuous motion sequence [math]\displaystyle{ \{m_t \in M | t \geq 0\} }[/math] generates continous image sequence [math]\displaystyle{ \{i_t \in I | t \geq 0\} }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ i_t=\pi(m_t(s)) }[/math]. Writing this as a hidden Markov model gives [math]\displaystyle{ i_t=\pi(m_{\Delta t}(s_{t-1}))) }[/math] where the current state is based on the change from the previous. Since [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is a closed group on [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math], it is associative, has inverse, and contains idenity. [math]\displaystyle{ SE(3) }[/math] is an exmaple of this. To be more specific, the latent structure of a scene from rigid image motion could be modelled by a point cloud with a motion space [math]\displaystyle{ M=SE(3) }[/math], where rigid image motion can be produced by a camera translating and rotating through a rigid scene in 3D. When a scene has N rigid bodies, the motion space can be represented as [math]\displaystyle{ M=[SE(3)]^N }[/math].

Learning Motion by Group Properties

The goal is to learn a function [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi : I \times I \rightarrow \overline{M} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{M} }[/math] indicating mapping of image pairs from [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] to its representation, as well as the composition operator [math]\displaystyle{ \diamond : \overline{M} \rightarrow \overline{M} }[/math] that emulates the composition of these elements in [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math]. For all sequences, it is assumed that for all times [math]\displaystyle{ t_0 \lt t_1 \lt t_2 ... }[/math], the sequence representation should have the following properties:

- Associativity: [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_2}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_2}, I_{t_3}) = (\Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_2})) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_2}, I_{t_3}) = \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond (\Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_2}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_2}, I_{t_3})) = \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_3}) }[/math], which means that the motion of differently composed subsequences of a sequence are equivalent

- Has Identity: [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond e = \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) = e \diamond \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ e=\Phi(I_{t}, I_{t}) \forall t }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] is the null image motion and the unique identity in the latent space

- Invertibility: [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_0}) = e }[/math], so the inverse of the motion of an image sequence is the motion of that image sequence reversed

Also note that a notion of transitivity is assumed, specifically [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_2}) = \Phi(I_{t_0}, I_{t_1}) \diamond \Phi(I_{t_1}, I_{t_2}) }[/math].

An embedding loss is used to approximately enforce associativity and invertibility among subsequences sampled from image sequence. Associativity is encouraged by pushing sequences with the same final motion but different transitions to the same representation. Invertibility is encouraged by pushing sequences corresponding to the same motion with but in opposite directions away from each other, as well as pushing all loops to the same representation. Uniqueness of the identity is encouraged by pushing loops away from non-identity representations. Loops from different sequences are also pushed to the same representation (the identity).

These constraints are true to any type of transformation resulting from image motion. This puts little restriction on the learning problems and allows all features relevant to the motion structure to be captured. On the other hand, optical flow assumes unchanging brightness between frames of the same projected scene, and motion estimates would degrade when that assumption does not hold.

Also with this method, it is possible multiple representations [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{M} }[/math] can be learned from a single [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math], thus the learned representation is not necessary unique. In addition, the scenes are not expected to have rapid changing content, scene cuts, or long-term occlusions.

Sequence Learning with Neural Networks

The functions [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \diamond }[/math] are approximated by CNN and RNN, respectively. LSTM is used for RNN. The input to the network is a sequence of images [math]\displaystyle{ I_t = \{I_1,...,I_t\} }[/math]. The CNN processes pairs of images and generates intermediate representations, and the LSTM operates over the sequence of CNN outputs to produce an embedding sequence [math]\displaystyle{ R_t = \{R_{1,2},...,R_{t-1,t}\} }[/math]. Only the embedding at the final time step is used for loss. The network is trained to minimize a hinge loss with respect to embeddings to pairs of sequences as defined below:

where [math]\displaystyle{ d(R^1,R^2) }[/math] measure the distance between the embeddings of two sequences used for training selected to be cosine distance, [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] is a fixed scalar margin selected to be 0.5. Positive pairs are training examples where two sequences have the same final motion, negative pairs are training examples where two sequences have the exact opposite final motion. Using L2 distances yields similar results as cosine distances.

Each training sequence is recomposed into 6 subsequences: two forward, two backward, and two identity. To prevent the network from only looking at static differences, subsequence pairs are sampled such that they have the same start and end frames but different motions in between. Sequences of varying lengths are also used to generalize motion on different temporal scales. Training the network with only one input images per time step was also tried, but consistently yielded work results than image pairs.

Overall, training with image pairs resulted in lower error than training with just single images. This is demonstrated in the below table.

Experimentation

Trained network using rotated and translated MNIST dataset as well as KITTI dataset.

- Used Torch

- Used Adam for optimization, decay schedule of 30 epochs, learning rate chosen by random serach

- 50-60 batch size for MNIST, 25-30 batch size for KITTI

- Dilated convolution with Relu and batch normalization

- Two LSTM cell per layer 256 hidden units each

- Sequence length of 3-5 images

- MINIST networks with up to 12 images

Rigid Motion in 2D

- MNIST data rotated [math]\displaystyle{ [0, 360) }[/math] degrees and translated [math]\displaystyle{ [-10, 10] }[/math] pixels, i.e. [math]\displaystyle{ SE(2) }[/math] transformations

- Visualized the representation using t-SNE

- Clear clustering by translation and rotation but not object classes

- Suggests the representation captures the motion properties in the dataset, but is independent of image contents

- Visualized the image-conditioned saliency maps

- In Figure 3, the red represents the positive gradients of the activation function with respect to the input image, and the negative gradients are represented in blue.

- If we consider a saliency map as a first-order Taylor expansion, then the map could show the relationship between pixel and the representation.

- Take derivative of the network output respect to the map

- The area that has the highest gradient means that part contributes the most to the output

- The resulting salient map strongly resembles spatiotemporal energy filters of classical motion processing

- Suggests the network is learning the right motion structure

Real World Motion in 3D

- Uses KITTI dataset collected on a car driving through roads in Germany

- On a separate dataset with ground truth camera pose, linearly regress the representation to the ground truth

- The result is compared against self supervised flow algorithm Yu et al.(2016) after the output from the flow algorithm is downsampled, then feed through PCA, then regressed against the camera motion

- The data shows it performs not as well as the supervised algorithm, but consistently better than chance (guessing the mean value)

- Largest improvements are shown in X and Z translation, which also have the most variance in the data

- Shows the method is able to capture dominant motion structure

- Test performance on interpolation task

- Check [math]\displaystyle{ R([I_1,I_T]) }[/math] against [math]\displaystyle{ R([I_1, I_m, I_T]) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ R([I_1, I_{IN}, I_T]) }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ R([I_1, I_{OUT}, I_T]) }[/math]

- Test how sensitive the network is to deviations from unnatural motion

- High errors [math]\displaystyle{ \gg 1 }[/math] means the network can distinguish between realistic and unrealistic motion

- In order to do this, the distance between the embeddings of the frame sequences of the first and last frame [math]\displaystyle{ R([I_1,I_T]) }[/math] and of the first, middle, and last frame [math]\displaystyle{ R([I_1, I_m, I_T]) }[/math] is computed. This distance is compared with the distance when the middle frame of the second embedding is changed to a frame that is visually similar (inside sequence): [math]\displaystyle{ R([I_1, I_{IN}, I_T]) }[/math] and one that is visually dissimilar (outside sequence): [math]\displaystyle{ R([I_1, I_{OUT}, I_T]) }[/math]. The results are shown in Table 3. The embedding distance method is compared to the Euclidean distance which is defined as the mean pixel distance between the test frame and [math]\displaystyle{ {I_1,I_T} }[/math], whichever is smaller. It can be seen from the results that the embedding distance of the true frame is significantly lower than other frames. This means that the embedding distance used in the network is more sensitive to any atypical motions of the scenes.

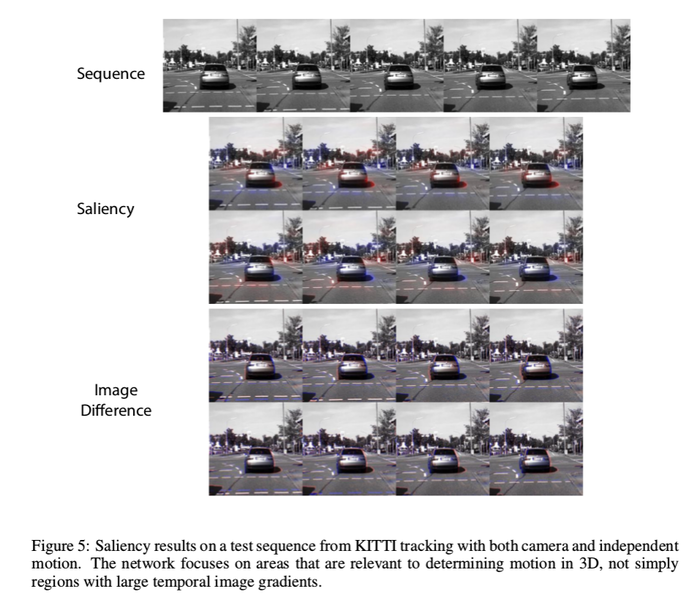

- Visualized saliency maps

- Highlights objects moving in the background, and motion of the car in the foreground

- Suggests the method can be used for tracking as well

- Figure 7 displays graphs comparing the mean squared error of the method presented in this paper to the baseline chance method and the supervised Flow PCA method.

Conclusion

The authors presented a new model of motion and a method for learning motion representations. It is shown that by enforcing group properties we can learn motion representations that are able to generalize between scenes with disparate content. The results can be useful for navigation, prediction, and other behavioral tasks relying on motion. Due to the fact that this method does not require labelled data, it can be applied to a large variety of tasks.

Criticism

Although this method does not require any labelled data, it is still learning by supervision through defined constraints. The idea of training using unlabelled data is interesting and it does have meaningful practical application. Unfortunately, the author did not provide convincing experimental results. Results from motion estimation problems are typically compared against ground truth data for their accuracy. The author performed experiments on transformed MNIST data and KITTI data. The MNIST data is transformed by the author, thus the ground truth is readily available. However the author only claimed the validity of the results through indirect means of using t-SNE and saliency map visualization. For the KITTI dataset, the author regressed the representations against ground truth for some mapping from the network output to some physical motion representation. Again, the results were compared only indirectly against ground truth, also shows poor results when compared with the Flow+PCA baseline, especially for X and Z translations as well as Y rotation, which are the main elements of motion present in the KITTI dataset. Such experimentation made the method hardly convincing and applicable to real-world applications. In addition, the network does not output motion representations with physical meanings, making the proposed method useless for any real world applications.

One of the motivations the authors use for this approach is that traditional SLAM formulations represent motion as a sequence of poses in [math]\displaystyle{ SE(3) }[/math], and that they are unable to represent non-rigid or independent motions. There exist SLAM formulations that represent motion as Gaussian processes, as well as temporal basis functions, and it is quite common for inertial, monocular-camera SLAM problems to use a motion representation on [math]\displaystyle{ SIM(3) }[/math], which is the group containing all scale-preserving transformations. A [math]\displaystyle{ SIM(3) }[/math] transformation is not, in general, rigid, so it is not true to say that modern SLAM is unable to represent non-rigid motions. Additionally, the saliency images from the KITTI experiment displaying network gradients on independently moving objects in the scene does not necessarily mean that the motion representation is capturing independent motion, it just means that the network representation is dependent on those pixels. As the authors did not provide an error comparison between images containing independent motions and those without, it is possible that these network gradients only contribute to error (in terms of the camera pose) instead of capturing independent motions.

Another criticism is that the group-properties constraint the authors impose is too weak. Any set consisting of functions, their inverses, and the identity forms a group. While physical motions are one example of such a group, there are many valid groups that do not represent any coherent physical motions. That is, it's unclear whether group representations adequately describe the underlying mechanisms of the paper.

Since the network has to learn both the group elements, [math]\displaystyle{ \overline{M} }[/math], and the composition function, [math]\displaystyle{ \diamond }[/math], associated with the group it is difficult to tell how each of them are performing. It would not be possible to perform a layer-by-layer ablation study to determine the individual contributions of the functions associated with each group.

Finally, the method requires domain knowledge of the motion space and feature engineering for encoding it, which reduces the ease with which the method can be generalized to various tasks.

References

Jaegle, A. (2018). Understanding image motion with group representations . ICLR. Retrieved from https://openreview.net/pdf?id=SJLlmG-AZ.

Karen Simonyan, Andrea Vedaldi, and Andrew Zisserman. Deep inside convolutional networks: Visualising image classification models and saliency maps. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) Workshop, 2013.

Jason J Yu, Adam W Harley, and Konstantinos G Derpanis. Back to basics: Unsupervised learning of optical flow via brightness constancy and motion smoothness. European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) Workshops, 2016.