stat946w18/IMPROVING GANS USING OPTIMAL TRANSPORT: Difference between revisions

| Line 56: | Line 56: | ||

Salimans et al. (2016) mentioned that comparing to use distributions over individual images, mini-batch GAN is more powerful when use the distributions over mini-batches <math> g(X), p(X) </math>. | |||

===GENERALIZED ENERGY DISTANCE=== | ===GENERALIZED ENERGY DISTANCE=== | ||

The generalized energy distance allowed to use non-Euclidean distance functions d. It is also valid for min-batches. | The generalized energy distance allowed to use non-Euclidean distance functions d. It is also valid for min-batches. | ||

Revision as of 19:11, 13 March 2018

Introduction

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are powerful generative models. A GAN model consists of a generator and a discriminator or critic. The generator is a neural network which is trained to generate data having a distribution matched with the distribution of the real data. The critic is also a neural network, which is trained to separate the generated data from the real data. A loss function that measures the distribution distance between the generated data and the real one is important to train the generator.

Optimal transport theory evaluates the distribution distance based on metric, which provides another method for generator training. The main advantage of optimal transport theory over the distance measurement in GAN is its closed form solution for having a tractable training process. But the theory might also result in inconsistency in statistical estimation due to the given biased gradients if the mini-batches method is applied.

This paper presents a variant GANs named OT-GAN, which incorporates a discriminative metric called 'MIni-batch Energy Distance' into its critic in order to overcome the issue of biased gradients.

GANs and Optimal Transport

Generative Adversarial Nets

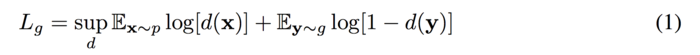

Original GAN was firstly reviewed. The objective function of the GAN:

The goal of GANs is to train the generator g and the discriminator d finding a pair of (g,d) to achieve Nash equilibrium. However, it could cause failure of converging since the generator and the discriminator are trained based on gradient descent techniques.

Wasserstein distance (Earth-Mover Distance)

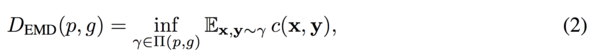

In order to solve the problem of convergence failure, Arjovsky et. al. (2017) suggested Wasserstein distance (Earth-Mover distance) based on the optimal transport theory.

where [math]\displaystyle{ \prod (p,g) }[/math] is the set of all joint distributions [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma (x,y) }[/math] with marginals [math]\displaystyle{ p(x) }[/math] (real data), [math]\displaystyle{ g(y) }[/math] (generated data) and [math]\displaystyle{ c(x,y) }[/math] is a cost function which takes to be the Euclidean distance.

The Earth-Mover Distance can be considered as moving the minimum amount of points between distribution [math]\displaystyle{ g(y) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ p(x) }[/math] such that the generator distribution [math]\displaystyle{ g(y) }[/math] is similar to the real data distribution [math]\displaystyle{ p(x) }[/math].

Consider that solving the Wasserstein distance is usually not possible, the proposed Wasserstein GAN (W-GAN) provides an estimated solution by switching the optimal transport problem into dual formulation using a set of 1-Lipschitz functions. A neural network can then be used to obtain an estimation.

W-GAN solves the unstable training process of original GAN and it can solve the optimal transport problem approximately, but it is still intractable.

The training process becomes traceable and a fully connected multi-layer network is sufficient for the training. However, the calculation of the Wasserstein distance is still an approximation and we can not have a fine-optimized critic.

Sinklhorn Distance

Genevay et al. (2017) proposed to use the primal formulation of optimal transport instead of the dual formulation to generative modeling. They introduced Sinkhorn distance which is a smoothed generalization of the Earth Mover distance.

![]()

It introduced a constant [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math] to restricted the entropy of the joint distribution [math]\displaystyle{ \prod_{\beta} (p,g) }[/math]. This distanc could generalize to approximate the mini-batches of data [math]\displaystyle{ X ,Y }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ K }[/math] vectors of [math]\displaystyle{ x, y }[/math]. The [math]\displaystyle{ i, j }[/math] th entry of the cost matrix [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] can be interpreted as the cost it needs to transport the [math]\displaystyle{ x_i }[/math] in mini-batch X to the [math]\displaystyle{ y_i }[/math] in mini-batch [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math]. The resulting distance will be:

where [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is a [math]\displaystyle{ K \times K }[/math] matrix, each row of [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is a joint distribution of [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma (x,y) }[/math] with positive entries. The summmation of rows or columns of [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is always equal to 1. Sinkhorn AutoDiff is the methods that minimiztion over M proposed by Genevay et al. (2017b)

This mini-batch Sinkhorn distance is not only fully tractable but also solve the instability problem of GANs. However, for the fixed mini-batch size, the gradients in this equation are biased.

Energy Distance (Cramer Distance)

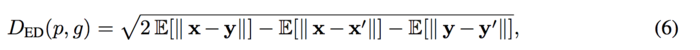

In order to solve the above problem, Energy Distance is proposed by Bellemare et al. (2017):

where [math]\displaystyle{ x, x' }[/math] are independent samples from data distribution [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y, y' }[/math] are independent samples from the generator distribution [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math]. Cramer GAN is the method that by minimizing the ED distance metric to training the generator.

MINI-BATCH ENERGY DISTANCE

Salimans et al. (2016) mentioned that comparing to use distributions over individual images, mini-batch GAN is more powerful when use the distributions over mini-batches [math]\displaystyle{ g(X), p(X) }[/math].

GENERALIZED ENERGY DISTANCE

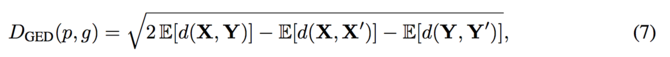

The generalized energy distance allowed to use non-Euclidean distance functions d. It is also valid for min-batches.

where [math]\displaystyle{ X, X' }[/math] are independent samples from data distribution [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ Y, Y' }[/math] are independent samples from the generator distribution [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math]. As long as [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] is a metric, [math]\displaystyle{ D_{GED}(p,g) }[/math] is a metric. Thus, by the defination of metric, [math]\displaystyle{ D(p,g) \geq 0, }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ D(p,g)=0 }[/math] iff [math]\displaystyle{ p=g }[/math].

MINI-BATCH ENERGY DISTANCE

Salimans et al. (2016) mentioned that comparing to use distributions over individual images, mini-batch GAN is more powerful when use the distributions over mini-batches [math]\displaystyle{ g(X), p(X) }[/math]. Here the author proposed a new metric, Mini-batch Energy Distance. It is a distance metric that combines the energy distance iwth primal form of optimal tranport over mini-batch distributions [math]\displaystyle{ g(Y) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ p(X) }[/math].