THE LOGICAL EXPRESSIVENESS OF GRAPH NEURAL NETWORKS: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

== Background == | == Background == | ||

Graph neural networks (GNNs) (Merkwirth & Lengauer, 2005; Scarselli et al., 2009) are a class of neural network architectures that have recently become popular for a wide range of applications dealing with structured data | Graph neural networks (GNNs) (Merkwirth & Lengauer, 2005; Scarselli et al., 2009) are a class of neural network architectures that have recently become popular for a wide range of applications dealing with structured data such as molecule classification, knowledge graph completion, and Web page ranking (Battaglia et al., 2018; Gilmer et al., 2017; Kipf & Welling, 2017; Schlichtkrull et al., 2018). The main idea behind GNNs is that the connections between neurons are not arbitrary but reflect the structure of the input data. This approach is motivated by convolutional and recurrent neural networks and generalizes to both of them (Battaglia et al., 2018). Despite the fact that GNNs have recently been proven very efficient in many applications, their theoretical properties are not yet well-understood. | ||

The ability of graph neural networks (GNNs) for distinguishing nodes in graphs has been recently characterized in terms of the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) test for checking graph isomorphism. The WL test works by constructing labeling of the nodes of the graph, in an incremental fashion, and then decides whether two graphs are isomorphic by comparing the labeling of each graph. This characterization, however, does not settle the issue of which Boolean node classifiers (i.e., functions classifying nodes in graphs as true or false) can be expressed by GNNs. To state the connection between GNNs and this test, consider the simple GNN architecture that updates the feature vector of each graph node by combining it with the | The ability of graph neural networks (GNNs) for distinguishing nodes in graphs has been recently characterized in terms of the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) test for checking graph isomorphism. The WL test works by constructing labeling of the nodes of the graph, in an incremental fashion, and then decides whether two graphs are isomorphic by comparing the labeling of each graph. This characterization, however, does not settle the issue of which Boolean node classifiers (i.e., functions classifying nodes in graphs as true or false) can be expressed by GNNs. To state the connection between GNNs and this test, consider the simple GNN architecture that updates the feature vector of each graph node by combining it with the aggregate of the feature vectors of its neighbors. Such GNNs are called aggregate-combine GNNs, or AC-GNNs. Moreover, there are AC-GNNs that can reproduce the WL labeling. This does not imply, however, that AC-GNNs can capture every node classifier—that is, a function assigning true or false to every node—that is refined by the WL test. This work aims to answer the question of what are the node classifiers that can be captured by GNN architectures such as AC-GNNs. | ||

== Introduction == | |||

They tackle this problem by focusing on boolean classifiers expressible as formulas in the logic FOC2, a well-studied fragment of first-order logic. FOC2 is tightly related to the WL test, and hence to GNNs. They start by studying a popular class of GNNs called AC-GNNs in which the features of each node in the graph are updated, in successive layers, only in terms of the features of its neighbors. Given the connection between AC-GNNs and WL on the one hand, and that between WL and FOC2 on the other hand, one may be tempted to think that the expressivity of AC-GNNs coincides with that of FOC2. However, the reality is not as simple, and there are many FOC2 node classifiers (e.g., the trivial one above) that cannot be expressed by AC-GNNs. This leaves us with the following natural questions. First, what is the largest fragment of FOC2 classifiers that can be captured by AC-GNNs? Second, is there an extension of AC-GNNs that allows expressing all FOC2 classifiers? In this paper, they provide answers to these two questions. | |||

The following are the main contributions: | |||

1. They characterize exactly the fragment of FOC2 formulas that can be expressed as AC-GNNs. This fragment corresponds to graded modal logic (de Rijke, 2000) or, equivalently, to the description logic ALCQ, which has received considerable attention in the knowledge representation community (Baader et al., 2003; Baader & Lutz, 2007). | |||

2. Next, they extend the AC-GNN architecture in a very simple way by allowing global readouts, where in each layer they also compute a feature vector for the whole graph and combine it with local aggregations; they call these aggregate-combine-readout GNNs (ACR-GNNs). These networks are a special case of the ones proposed by Battaglia et al. (2018) for relational reasoning over graph representations. In this setting, they prove that an ACR-GNN can capture each FOC2 formula. | |||

They experimentally validate their findings showing that the theoretical expressiveness of ACR-GNNs, as well as the differences between AC-GNNs and ACR-GNNs, can be observed when they learn from examples. In particular, they show that on synthetic graph data conforming to FOC2 formulas, AC-GNNs struggle to fit the training data while ACR-GNNs can generalize even to graphs of sizes not seen during training. | |||

The | == Architecture == | ||

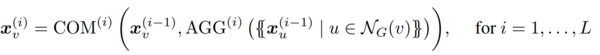

This paper concentrates on the problem of boolean node classification: given a (simple, undirected) graph G = (V, E) in which each vertex v ∈ V has an associated feature vector xv, the authors aim to classify each graph node as true or false. This paper assumes that these feature vectors are one-hot encodings of node colors in the graph, from a finite set of colors. The neighborhood NG(v) of a node v ∈ V is the set {u | {v, u} ∈ E}. The basic architecture for GNNs, and the one studied in recent studies on GNN expressibility (Morris et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019), consists of a sequence of layers that combine the feature vectors of every node with the multiset of feature vectors of its neighbors. Formally, let AGG and COM be two sets of aggregation and combination functions. An aggregate-combine GNN (AC-GNN) computes vectors <math>{x_v}^i</math> for every node v of the graph G, via the recursive formula | |||

[[File:a227-formula.png|600px|center|Image: 600 pixels]] | |||

Where each <math>{x_v}^0</math> is the initial feature vector <math>{x_v}</math> of v. Finally, each node v of G is classified according to a boolean classification function CLS applied to <math>{x_v}^{(L)}</math> | |||

== Concepts == | |||

=== 1. LOGICAL NODE CLASSIFIER === | |||

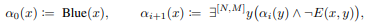

Their study relates the power of GNNs to that of classifiers expressed in first-order (FO) predicate logic over (undirected) graphs where each vertex has a unique color (recall that they call these classifiers logical classifiers). For example, | |||

\[ | |||

\alpha(x) := Red(x) \land \exists y (E(x,u) \land Blue(y)) \land \exists z (E(x,z) \land Green(z)) | |||

\] | |||

has one free variable namely, <math> x </math> and two quantified variables <math> y </math> and <math> z </math>. Formally, the authors defined the following definition for a logical node calssifier. | |||

'''Definition 3.1''' A GNN classifier <math> \mathcal{A} </math> captures a logical classifier <math> \varphi (x) </math> if for every graph G and node v in G, it holds that <math> \mathcal{A}(G,v) = \textrm{true} </math> if and only if <math> (G,v) \models \varphi </math>. | |||

=== 2. LOGIC FOC2 === | |||

The logic FOC2 allows for formulas using all FO constructs and counting quantifiers, but restricted to only two variables. Note that in terms of their logical expressiveness, FOC2 is strictly less expressive than FO (as counting quantifiers can always be mimicked in FO by using more variables and disequalities), but is strictly more expressive than FO2 - the fragment of FO that allows formulas to use only two variables (as β(x) belongs to FOC2 but not to FO2). The author gives the following proposition regarding the choice of logic FOC2 for measuring the expressiveness of AC-GNNs. | |||

'''Proposition 3.2''' For any graph G and nodes u,v in G, the WL test colors v and u the same after any number of rounds if and only if u and v are classified the same by all FOC2 classifiers. | |||

=== 3. FOC2 AND AC-GNN CLASSIFIER === | |||

While it is true that two nodes are declared indistinguishable by the WL test if and only if they are indistinguishable by all FOC2 classifiers (Proposition 3.2), and if the former holds then such nodes cannot be distinguished by AC-GNNs (Proposition 2.1), this by no means tells us that every FOC2 classifier can be expressed as an AC-GNN. The answer to this problem is covered in the next section. | |||

=== THE EXPRESSIVE POWER OF AC-GNNS === | |||

AC-GNNs capture any FOC2 classifier as long as they further restrict the formulas so that they satisfy such a locality property. This happens to be a well-known restriction of FOC2 and corresponds to graded modal logic (de Rijke, 2000), which is fundamental for knowledge representation. The idea of graded modal logic is to force all sub-formulas to be guarded by the edge predicate E. This means that one cannot express in graded modal logic arbitrary formulas of the form ∃yϕ(y), i.e., whether some node satisfies property ϕ. Instead, one is allowed to check whether some neighbor y of the node x where the formula is being evaluated satisfies ϕ. That is, they are allowed to express the formula ∃y (E(x, y) ∧ ϕ(y)) in the logic as in this case ϕ(y) is guarded by E(x, y). | |||

The relationship between AC-GNNs and graded modal logic goes further: they can show that graded modal logic is the “largest” class of logical classifiers captured by AC-GNNs. This means that the only FO formulas that AC-GNNs are able to learn accurately are those in graded modal logic. | |||

According to their theorem, a logical classifier is captured by AC-GNNs if and only if it can be expressed in graded modal logic. This holds no matter which aggregate and combines operators are considered, i.e., this is a limitation of the architecture for AC-GNNs, not of the specific functions that one chooses to update the features. | |||

The | The backward direction of this theorem is that a simple homogeneous AC-GNN captures each graded modal logic classifier. | ||

They point out that the forward direction holds no matter which aggregate and combine operators are considered, i.e., this is a limitation of the architecture for AC-GNNs, not of the specific functions that one chooses to update the features. | |||

=== ACR-GNNs === | |||

The main shortcoming of AC-GNNs for expressing such classifiers is their local behavior. A natural way to break such a behavior is to allow for a global feature computation on each layer of the GNN. This is called a global attribute computation in the framework of Battaglia et al. (2018). Following the recent GNN literature (Gilmer et al., 2017; Morris et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019), they refer to this global operation as a readout. Formally, an aggregate-combine-readout GNN (ACR-GNN) extends AC-GNNs by specifying readout functions READ(i), which aggregate the current feature vectors of all the nodes in a graph. | |||

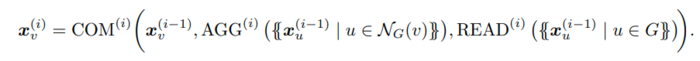

Then, the vector <math>{x_v}^i</math> of each node v in G on each layer i is computed by the following formula: | |||

[[File:a227-formula-final.png|700px|center|Image: 700 pixels]] | |||

Intuitively, every layer in an ACR-GNN first computes (i.e., “reads out”) the aggregation over all the nodes in G; then, for every node v, it computes the aggregation over the neighbors of v; and finally, it combines the features of v with the two aggregation vectors. | |||

They know that AC-GNNs cannot capture this classifier. However, using a single readout plus local aggregations one can implement this classifier as follows. First, define by B the property as “having at least 2 blue neighbors”. Then an ACR-GNN that implements γ(x) can (1) use one aggregation to store in the local feature of every node if the node satisfies B, then (2) use a readout function to count how many nodes satisfying B exist in the whole graph, and (3) use another local aggregation to count how many neighbors of every node satisfy B. | |||

They then show that just one readout is enough. However, this reduction in the number of readouts comes at the cost of severely complicating the resulting GNN. Formally, an aggregate-combine GNN with final readout (AC-FR-GNN) results from using any number of layers as in the AC-GNN definition, together with a final layer uses a readout function. | |||

== | == Experiments == | ||

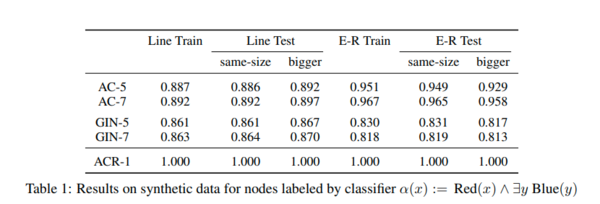

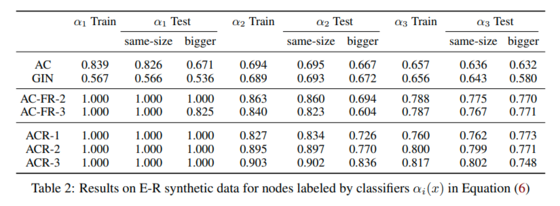

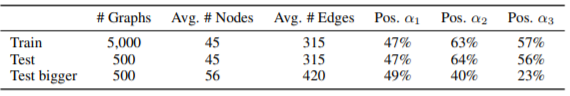

The authors performed experiments with synthetic data to empirically validate their results. They perform two sets of experiments: experiments to show that ACR-GNNs can learn a very simple FOC2 node classifier that AC-GNNs cannot learn, and experiments involving complex FOC2 classifiers that need more intermediate readouts to be learned. Besides testing simple AC-GNNs, they also tested the GIN network proposed by Xu et al. (2019) (they consider the implementation by Fey & Lenssen (2019) and adapted it to classify nodes). Their experiments use synthetic graphs, with five initial colors encoded as one-hot features, divided into three sets: the train set with 5k graphs of size up to 50-100 nodes, the test set with 500 graphs of a size similar to the train set, and another test set with 500 graphs of size bigger than the train set. They tried several configurations for the aggregation, combination readout functions, and report the accuracy on the best configuration. In their experiments, accuracy is computed as the total number of nodes correctly classified among all nodes in all the graphs in the dataset. In every case, they run up to 20 epochs with the Adam optimizer. | |||

In | |||

[[File: | [[File:a227_table1.png|600px|center|Image: 600 pixels]] | ||

[[File:a227_table2.png|560px|center|Image: 600 pixels]] | |||

For both types of graphs, already single-layer ACR-GNNs showed perfect performance (ACR-1 in Table 1). This was what they expected given the simplicity of the property being checked. In contrast, AC-GNNs and GINs (shown in Table 1 as AC-L and GINL, representing AC-GNNs and GINs with L layers) struggle to fit the data. For the case of the line-shaped graph, they were not able to fit the train data even by allowing 7 layers. For the case of random graphs, the performance with 7 layers was considerably better. | |||

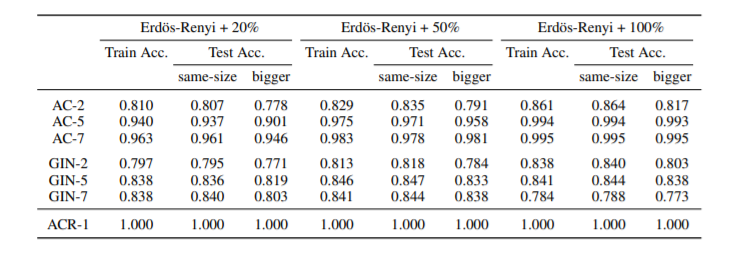

Table 2 above corresponds to the results E-R synthetic data for nodes labeled by the below classifier. ACR-GNNs performance up to 3 layers is reported. For the bigger test set, it was also observed that AC-GNNs and GINs are unable to substantially depart from a trivial baseline of 50%. | |||

[[File: | [[File:a227eq6.png|400px|center|Image: 400 pixels]] | ||

'''Statistics of the datasets used for the above equation is shown below''' | |||

[[File:Paper13_Statistics_Dataset.png|center]] | |||

Results for Erdos-Renyi synthetic graphs with different connectivities are shown below | |||

[[File:CaptureLogical.PNG|center]] | |||

== Final Remarks == | |||

The paper's results show the theoretical advantages of mixing local and global information when classifying nodes in a graph. Recent works have also observed these advantages in practice, e.g., Deng et al. published as a conference paper at ICLR 2020 (2018) use global-context aware local descriptors to classify objects in 3D point clouds, You et al. (2019) construct node features by computing shortest-path distances to a set of distant anchor nodes, and Haonan et al. (2019) introduced the idea of a “star node” that stores global information of the graph. As mentioned before, their work is close in spirit to that of Xu et al. (2019) and Morris et al. (2019) establishing the correspondence between the WL test and GNNs. | |||

Regarding the results on the links between AC-GNNs and graded modal logic (Theorem 4.2), the very recent work of Sato et al. (2019) establishes close relationships between GNNs and certain classes of distributed local algorithms. These in turn have been shown to have strong correspondences with modal logics (Hella et al., 2015). | |||

== Source Code == | |||

The code for this paper is freely available at [https://github.com/juanpablos/GNN-logic link GNN-logic] | |||

== Conclusion == | == Conclusion == | ||

The authors were successful in establishing their claims with the help of ACR-GNNs. The results show the theoretical advantages of mixing local and global information when classifying nodes in a graph. Recent works have also observed these advantages in practice, e.g., Deng et al. published as a conference paper at ICLR 2020 (2018) use global-context aware local descriptors to classify objects in 3D point clouds. | |||

The authors would like to study how their results can be applied for extracting logical formulas from GNNs as possible explanations for their computations. | |||

== Critiques== | == Critiques== | ||

The paper has been quite successful in solving the problem of binary classifiers in GNNs. The paper was released in 2019 and has already been cited 22 times. The content structure is very well organized, and the explanations are easy to understand for an average reader. They have also discussed future work and possibilities. They could have given more commentary about the performance difference across different classifiers. | |||

The fact that no actual difference in performance between AC-GNNs and ACR-GNNs was noticed in the only non-synthetic dataset used in the experiment should prompt the author to run experiments with more real-life datasets to verify the results empirically. | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

[1] | [1] Franz Baader and Carsten Lutz. Description logic. In Handbook of modal logic, pp. 757–819. North-Holland, 2007. | ||

[2] | [2] Franz Baader, Diego Calvanese, Deborah L. McGuinness, Daniele Nardi, and Peter F. PatelSchneider (eds.). The description logic handbook: theory, implementation, and applications. Cambridge University Press, 2003. | ||

[3] | [3] Peter W. Battaglia, Jessica B. Hamrick, Victor Bapst, Alvaro Sanchez-Gonzalez, Vin´ıcius Flores Zambaldi, Mateusz Malinowski, Andrea Tacchetti, David Raposo, Adam Santoro, Ryan Faulkner, C¸ aglar Gulc¸ehre, H. Francis Song, Andrew J. Ballard, Justin Gilmer, George E. Dahl, Ashish ¨ Vaswani, Kelsey R. Allen, Charles Nash, Victoria Langston, Chris Dyer, Nicolas Heess, Daan Wierstra, Pushmeet Kohli, Matthew Botvinick, Oriol Vinyals, Yujia Li, and Razvan Pascanu. Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. CoRR, abs/1806.01261, 2018. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1806.01261. | ||

[4] | [4] Jin-Yi Cai, Martin Furer, and Neil Immerman. ¨ An optimal lower bound on the number of variables for graph identification. Combinatorica, 12(4):389–410, 1992. | ||

[5] | [5] Ting Chen, Song Bian, and Yizhou Sun. Are powerful graph neural nets necessary? A dissection on graph classification. CoRR, abs/1905.04579, 2019. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.04579. | ||

Latest revision as of 17:02, 6 December 2020

Presented By

Abhinav Jain

Background

Graph neural networks (GNNs) (Merkwirth & Lengauer, 2005; Scarselli et al., 2009) are a class of neural network architectures that have recently become popular for a wide range of applications dealing with structured data such as molecule classification, knowledge graph completion, and Web page ranking (Battaglia et al., 2018; Gilmer et al., 2017; Kipf & Welling, 2017; Schlichtkrull et al., 2018). The main idea behind GNNs is that the connections between neurons are not arbitrary but reflect the structure of the input data. This approach is motivated by convolutional and recurrent neural networks and generalizes to both of them (Battaglia et al., 2018). Despite the fact that GNNs have recently been proven very efficient in many applications, their theoretical properties are not yet well-understood.

The ability of graph neural networks (GNNs) for distinguishing nodes in graphs has been recently characterized in terms of the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) test for checking graph isomorphism. The WL test works by constructing labeling of the nodes of the graph, in an incremental fashion, and then decides whether two graphs are isomorphic by comparing the labeling of each graph. This characterization, however, does not settle the issue of which Boolean node classifiers (i.e., functions classifying nodes in graphs as true or false) can be expressed by GNNs. To state the connection between GNNs and this test, consider the simple GNN architecture that updates the feature vector of each graph node by combining it with the aggregate of the feature vectors of its neighbors. Such GNNs are called aggregate-combine GNNs, or AC-GNNs. Moreover, there are AC-GNNs that can reproduce the WL labeling. This does not imply, however, that AC-GNNs can capture every node classifier—that is, a function assigning true or false to every node—that is refined by the WL test. This work aims to answer the question of what are the node classifiers that can be captured by GNN architectures such as AC-GNNs.

Introduction

They tackle this problem by focusing on boolean classifiers expressible as formulas in the logic FOC2, a well-studied fragment of first-order logic. FOC2 is tightly related to the WL test, and hence to GNNs. They start by studying a popular class of GNNs called AC-GNNs in which the features of each node in the graph are updated, in successive layers, only in terms of the features of its neighbors. Given the connection between AC-GNNs and WL on the one hand, and that between WL and FOC2 on the other hand, one may be tempted to think that the expressivity of AC-GNNs coincides with that of FOC2. However, the reality is not as simple, and there are many FOC2 node classifiers (e.g., the trivial one above) that cannot be expressed by AC-GNNs. This leaves us with the following natural questions. First, what is the largest fragment of FOC2 classifiers that can be captured by AC-GNNs? Second, is there an extension of AC-GNNs that allows expressing all FOC2 classifiers? In this paper, they provide answers to these two questions.

The following are the main contributions:

1. They characterize exactly the fragment of FOC2 formulas that can be expressed as AC-GNNs. This fragment corresponds to graded modal logic (de Rijke, 2000) or, equivalently, to the description logic ALCQ, which has received considerable attention in the knowledge representation community (Baader et al., 2003; Baader & Lutz, 2007).

2. Next, they extend the AC-GNN architecture in a very simple way by allowing global readouts, where in each layer they also compute a feature vector for the whole graph and combine it with local aggregations; they call these aggregate-combine-readout GNNs (ACR-GNNs). These networks are a special case of the ones proposed by Battaglia et al. (2018) for relational reasoning over graph representations. In this setting, they prove that an ACR-GNN can capture each FOC2 formula.

They experimentally validate their findings showing that the theoretical expressiveness of ACR-GNNs, as well as the differences between AC-GNNs and ACR-GNNs, can be observed when they learn from examples. In particular, they show that on synthetic graph data conforming to FOC2 formulas, AC-GNNs struggle to fit the training data while ACR-GNNs can generalize even to graphs of sizes not seen during training.

Architecture

This paper concentrates on the problem of boolean node classification: given a (simple, undirected) graph G = (V, E) in which each vertex v ∈ V has an associated feature vector xv, the authors aim to classify each graph node as true or false. This paper assumes that these feature vectors are one-hot encodings of node colors in the graph, from a finite set of colors. The neighborhood NG(v) of a node v ∈ V is the set {u | {v, u} ∈ E}. The basic architecture for GNNs, and the one studied in recent studies on GNN expressibility (Morris et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019), consists of a sequence of layers that combine the feature vectors of every node with the multiset of feature vectors of its neighbors. Formally, let AGG and COM be two sets of aggregation and combination functions. An aggregate-combine GNN (AC-GNN) computes vectors [math]\displaystyle{ {x_v}^i }[/math] for every node v of the graph G, via the recursive formula

Where each [math]\displaystyle{ {x_v}^0 }[/math] is the initial feature vector [math]\displaystyle{ {x_v} }[/math] of v. Finally, each node v of G is classified according to a boolean classification function CLS applied to [math]\displaystyle{ {x_v}^{(L)} }[/math]

Concepts

1. LOGICAL NODE CLASSIFIER

Their study relates the power of GNNs to that of classifiers expressed in first-order (FO) predicate logic over (undirected) graphs where each vertex has a unique color (recall that they call these classifiers logical classifiers). For example, \[ \alpha(x) := Red(x) \land \exists y (E(x,u) \land Blue(y)) \land \exists z (E(x,z) \land Green(z)) \] has one free variable namely, [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and two quantified variables [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ z }[/math]. Formally, the authors defined the following definition for a logical node calssifier.

Definition 3.1 A GNN classifier [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{A} }[/math] captures a logical classifier [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi (x) }[/math] if for every graph G and node v in G, it holds that [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{A}(G,v) = \textrm{true} }[/math] if and only if [math]\displaystyle{ (G,v) \models \varphi }[/math].

2. LOGIC FOC2

The logic FOC2 allows for formulas using all FO constructs and counting quantifiers, but restricted to only two variables. Note that in terms of their logical expressiveness, FOC2 is strictly less expressive than FO (as counting quantifiers can always be mimicked in FO by using more variables and disequalities), but is strictly more expressive than FO2 - the fragment of FO that allows formulas to use only two variables (as β(x) belongs to FOC2 but not to FO2). The author gives the following proposition regarding the choice of logic FOC2 for measuring the expressiveness of AC-GNNs.

Proposition 3.2 For any graph G and nodes u,v in G, the WL test colors v and u the same after any number of rounds if and only if u and v are classified the same by all FOC2 classifiers.

3. FOC2 AND AC-GNN CLASSIFIER

While it is true that two nodes are declared indistinguishable by the WL test if and only if they are indistinguishable by all FOC2 classifiers (Proposition 3.2), and if the former holds then such nodes cannot be distinguished by AC-GNNs (Proposition 2.1), this by no means tells us that every FOC2 classifier can be expressed as an AC-GNN. The answer to this problem is covered in the next section.

THE EXPRESSIVE POWER OF AC-GNNS

AC-GNNs capture any FOC2 classifier as long as they further restrict the formulas so that they satisfy such a locality property. This happens to be a well-known restriction of FOC2 and corresponds to graded modal logic (de Rijke, 2000), which is fundamental for knowledge representation. The idea of graded modal logic is to force all sub-formulas to be guarded by the edge predicate E. This means that one cannot express in graded modal logic arbitrary formulas of the form ∃yϕ(y), i.e., whether some node satisfies property ϕ. Instead, one is allowed to check whether some neighbor y of the node x where the formula is being evaluated satisfies ϕ. That is, they are allowed to express the formula ∃y (E(x, y) ∧ ϕ(y)) in the logic as in this case ϕ(y) is guarded by E(x, y).

The relationship between AC-GNNs and graded modal logic goes further: they can show that graded modal logic is the “largest” class of logical classifiers captured by AC-GNNs. This means that the only FO formulas that AC-GNNs are able to learn accurately are those in graded modal logic.

According to their theorem, a logical classifier is captured by AC-GNNs if and only if it can be expressed in graded modal logic. This holds no matter which aggregate and combines operators are considered, i.e., this is a limitation of the architecture for AC-GNNs, not of the specific functions that one chooses to update the features.

The backward direction of this theorem is that a simple homogeneous AC-GNN captures each graded modal logic classifier. They point out that the forward direction holds no matter which aggregate and combine operators are considered, i.e., this is a limitation of the architecture for AC-GNNs, not of the specific functions that one chooses to update the features.

ACR-GNNs

The main shortcoming of AC-GNNs for expressing such classifiers is their local behavior. A natural way to break such a behavior is to allow for a global feature computation on each layer of the GNN. This is called a global attribute computation in the framework of Battaglia et al. (2018). Following the recent GNN literature (Gilmer et al., 2017; Morris et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019), they refer to this global operation as a readout. Formally, an aggregate-combine-readout GNN (ACR-GNN) extends AC-GNNs by specifying readout functions READ(i), which aggregate the current feature vectors of all the nodes in a graph. Then, the vector [math]\displaystyle{ {x_v}^i }[/math] of each node v in G on each layer i is computed by the following formula:

Intuitively, every layer in an ACR-GNN first computes (i.e., “reads out”) the aggregation over all the nodes in G; then, for every node v, it computes the aggregation over the neighbors of v; and finally, it combines the features of v with the two aggregation vectors.

They know that AC-GNNs cannot capture this classifier. However, using a single readout plus local aggregations one can implement this classifier as follows. First, define by B the property as “having at least 2 blue neighbors”. Then an ACR-GNN that implements γ(x) can (1) use one aggregation to store in the local feature of every node if the node satisfies B, then (2) use a readout function to count how many nodes satisfying B exist in the whole graph, and (3) use another local aggregation to count how many neighbors of every node satisfy B.

They then show that just one readout is enough. However, this reduction in the number of readouts comes at the cost of severely complicating the resulting GNN. Formally, an aggregate-combine GNN with final readout (AC-FR-GNN) results from using any number of layers as in the AC-GNN definition, together with a final layer uses a readout function.

Experiments

The authors performed experiments with synthetic data to empirically validate their results. They perform two sets of experiments: experiments to show that ACR-GNNs can learn a very simple FOC2 node classifier that AC-GNNs cannot learn, and experiments involving complex FOC2 classifiers that need more intermediate readouts to be learned. Besides testing simple AC-GNNs, they also tested the GIN network proposed by Xu et al. (2019) (they consider the implementation by Fey & Lenssen (2019) and adapted it to classify nodes). Their experiments use synthetic graphs, with five initial colors encoded as one-hot features, divided into three sets: the train set with 5k graphs of size up to 50-100 nodes, the test set with 500 graphs of a size similar to the train set, and another test set with 500 graphs of size bigger than the train set. They tried several configurations for the aggregation, combination readout functions, and report the accuracy on the best configuration. In their experiments, accuracy is computed as the total number of nodes correctly classified among all nodes in all the graphs in the dataset. In every case, they run up to 20 epochs with the Adam optimizer.

For both types of graphs, already single-layer ACR-GNNs showed perfect performance (ACR-1 in Table 1). This was what they expected given the simplicity of the property being checked. In contrast, AC-GNNs and GINs (shown in Table 1 as AC-L and GINL, representing AC-GNNs and GINs with L layers) struggle to fit the data. For the case of the line-shaped graph, they were not able to fit the train data even by allowing 7 layers. For the case of random graphs, the performance with 7 layers was considerably better.

Table 2 above corresponds to the results E-R synthetic data for nodes labeled by the below classifier. ACR-GNNs performance up to 3 layers is reported. For the bigger test set, it was also observed that AC-GNNs and GINs are unable to substantially depart from a trivial baseline of 50%.

Statistics of the datasets used for the above equation is shown below

Results for Erdos-Renyi synthetic graphs with different connectivities are shown below

Final Remarks

The paper's results show the theoretical advantages of mixing local and global information when classifying nodes in a graph. Recent works have also observed these advantages in practice, e.g., Deng et al. published as a conference paper at ICLR 2020 (2018) use global-context aware local descriptors to classify objects in 3D point clouds, You et al. (2019) construct node features by computing shortest-path distances to a set of distant anchor nodes, and Haonan et al. (2019) introduced the idea of a “star node” that stores global information of the graph. As mentioned before, their work is close in spirit to that of Xu et al. (2019) and Morris et al. (2019) establishing the correspondence between the WL test and GNNs.

Regarding the results on the links between AC-GNNs and graded modal logic (Theorem 4.2), the very recent work of Sato et al. (2019) establishes close relationships between GNNs and certain classes of distributed local algorithms. These in turn have been shown to have strong correspondences with modal logics (Hella et al., 2015).

Source Code

The code for this paper is freely available at link GNN-logic

Conclusion

The authors were successful in establishing their claims with the help of ACR-GNNs. The results show the theoretical advantages of mixing local and global information when classifying nodes in a graph. Recent works have also observed these advantages in practice, e.g., Deng et al. published as a conference paper at ICLR 2020 (2018) use global-context aware local descriptors to classify objects in 3D point clouds. The authors would like to study how their results can be applied for extracting logical formulas from GNNs as possible explanations for their computations.

Critiques

The paper has been quite successful in solving the problem of binary classifiers in GNNs. The paper was released in 2019 and has already been cited 22 times. The content structure is very well organized, and the explanations are easy to understand for an average reader. They have also discussed future work and possibilities. They could have given more commentary about the performance difference across different classifiers.

The fact that no actual difference in performance between AC-GNNs and ACR-GNNs was noticed in the only non-synthetic dataset used in the experiment should prompt the author to run experiments with more real-life datasets to verify the results empirically.

References

[1] Franz Baader and Carsten Lutz. Description logic. In Handbook of modal logic, pp. 757–819. North-Holland, 2007.

[2] Franz Baader, Diego Calvanese, Deborah L. McGuinness, Daniele Nardi, and Peter F. PatelSchneider (eds.). The description logic handbook: theory, implementation, and applications. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

[3] Peter W. Battaglia, Jessica B. Hamrick, Victor Bapst, Alvaro Sanchez-Gonzalez, Vin´ıcius Flores Zambaldi, Mateusz Malinowski, Andrea Tacchetti, David Raposo, Adam Santoro, Ryan Faulkner, C¸ aglar Gulc¸ehre, H. Francis Song, Andrew J. Ballard, Justin Gilmer, George E. Dahl, Ashish ¨ Vaswani, Kelsey R. Allen, Charles Nash, Victoria Langston, Chris Dyer, Nicolas Heess, Daan Wierstra, Pushmeet Kohli, Matthew Botvinick, Oriol Vinyals, Yujia Li, and Razvan Pascanu. Relational inductive biases, deep learning, and graph networks. CoRR, abs/1806.01261, 2018. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1806.01261.

[4] Jin-Yi Cai, Martin Furer, and Neil Immerman. ¨ An optimal lower bound on the number of variables for graph identification. Combinatorica, 12(4):389–410, 1992.

[5] Ting Chen, Song Bian, and Yizhou Sun. Are powerful graph neural nets necessary? A dissection on graph classification. CoRR, abs/1905.04579, 2019. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/1905.04579.